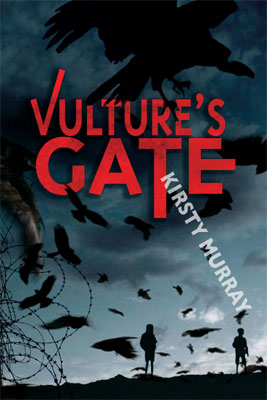

Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate

This futuristic thriller marks an exciting departure for award-winning novelist Kirsty Murray. Vulture's Gate is a gripping, fast-paced adventure set in outback Australia and in post-plague Sydney, several decades from now.

Callum has two dads, and knows that whispered talk of girls is just a myth- they were wiped out years ago by a viral plague. After being kidnapped and sold to a travelling circus, Callum steals a motorcycle and GPS and heads out into the desert. He is hunted down by a herd of robo-raptors and wakes to find himself in the lair of Bo, who lives alone in an opal burrow in central Australia's. Bo and Callum decide to set out for Vulture's Gate in search of Callum's lost fathers. What they find is a derelict city at the mercy of gangs and colliders, with a disturbing secret at its core�

In a world where there are almost no girls, Bo and Callum discover that the few that still exist are being captured, imprisoned, and cold-bloodedly 'harvested'.

With a vividly realised setting in futuristic Australia, Kirsty Murray's new novel is a provocative page-turner with a chilling social twist. It explores the kind of dystopia the world could become if women were scarce and there were no safeguards on the uses of genetic science.

'I absolutely loved it! I was intrigued after the very first page and remained so until the last world. The world Kirsty Murray has created is fascinating. It's so innovative� and yet at the same time believable. I don't know how she did it.' - Jasmine, teen reader.

Note from the Author

Young people's fiction should reflect the same events and ideas that are being discussed in the adult world. Children are not a separate sub-culture. They own the future and should be party to discussion about how it will be shaped.

I've had a long-standing interest in writing on popular science and had followed the coverage of the avian flu virus, advances in reproductive technologies and contemporary alarmist theories about the future of gender relationships.

Bryan Sykes best-selling book on genetics, Adam's Curse: A future without men (2003) is a book that eld to a flurry of alarmist articles about 'Fragile Y' (chromosome). Sykes' suggestion that women are winning the evolutionary battle of the sexes had everyone from educators to social commentators worrying about how badly men and boys were faring in the modern world� the idea that the position of boys and men in culture needed shoring up struck me as fairly amusing.

In 2004, another provocative non0fiction book appeared that tied into my think about what might happen if you reversed the premise of 'Fragile Y'. Bare Branches by, Valerie Hudson and Andrea den Boer, is a meticulously researched scholarly work that examines the security implication of Asia's surplus male population. Historically, high male-to-female ratios have often triggered domestic and international violence. Most violent crime is committed by young, unmarried males who lack stable social bonds. Governments sometimes respond to this problem by enlisting young surplus males in military campaigns and high-risk public works projects. Countries with high male-to-female ratios also tend to develop authorizes political systems.

While travelling in India, I was perplexed by the signs in health clinics announcing parents would not be told the gender of their unborn child as it was against the law to inform them. This is in an effort to reduce selective female abortions. India does not condone the practice but is struggling to come to terms with the problem. Through offspring sex section (often the form of sex-selective abortion and female infanticide) both India and China have a disproportionate number of low-status young adult males, called 'bare brashness' by the Chinese.

Although commentators have focused their concern on Asia, where men are markedly in excess of females, I believe this is a problem for the world and a reflection of ancient and deeply held fears and beliefs. Without human intervention, Nature ordains that there should be more women than men; yet there are over 50 million more men in the world than women.

All these disparate threads began to come together to form the ideas that support Vulture's Gate. I started to play around with the notion of a world where bird flu had damaged all X chromosomes so thoroughly that the ability of humans to reproduce female children was compromised. I started to think about what would happen if Nature began imitating culture. Just as we often reflect upon art imitating Nature, what happens if the choices we make as a species become reinforced by Nature?

Futurist Freeman Dyson has suggested that the 21st century will be 'the century of biology' and yet, I've been surprised at how few of the recent crop of dystopian fictions have explored the role bio-technology man play in changing gender relations. I knew of plenty of fiction that explored the idea of a world without men- the idea seemed to generate enough fear to create a whole body of science fiction from Virgin Planet (Anderson, 1959) to the recent comic book series Y: The Last Man. The future is envisioned as a place where men are peripheral. Inverting those expectations offered me a lot of potential for exploring metaphorical truths.

Children, like adults, are intrigued by the future. More than anyone else, children have a vested interest in envisioning the world of tomorrow. Contemporary teenagers in particular are keenly aware that they are going to have to live with the consequences of the older generation actions. In writing Vulture's Gate, I found that the characters of Bo and Callum propelled the story. Their youthful energy, optimism and strength made it possible to explore a darker reality without producing a book that was utterly black and nihilistic.

For all the above, Vulture's Gate is not didactic. I don't enjoy reading, nor do I wish to write, preachy, pontificating fiction for younger readers. I want the book to provoke the reader to think, and for the action to draw them on through the story. Nor do I have hard and fast conclusions to the dilemmas that Vulture's Gate throws at the reader. Good fiction should create argument, should challenge us to draw our own conclusions, not provide blanket statements about the meaning of live and the consequences of our actions.

Kirsty Murray is the author of many novels including Zarconi's Magic Flying Fish (winner of the WA Premier's Children's Book Award, 2001), Market Blues and Walking Home with Marie Claire. She has also published several non-fiction books for children and the Children of the Wind quartet of Irish-Australian novels- Bridie's Fire, Becoming Billy Dare, A Prayer for Blue Delaney and The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong.

Kirsty's novels have won and been short-listed for numerous awards including the WA Premier's Award and the NSW Premier's History Award. She has been a Creative Fellow of the State Library of Victoria and an Asialink Literature Resident in South India. She lives in Melbourne with her husband and a drifting tribe of young people.

Previous Books:

Zarconi's Magic Flying Gish (1999)

Market Blues (2001)

Walking Home with Marie-Claire (2002)

Children of the Wind series:

Bridie's Fire (2003)

A Prayer for Blue Delaney (2004)

Becoming Billy Dare (2005)

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong (2006)

Vulture's Gate

Allen and Unwin

Author: Kirsty Murray

Price: $15.99

MORE