Marzipan and Magnolias Inteview with Elizabeth Lancaster

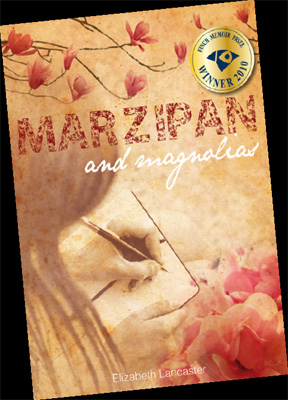

Marzipan and Magnolias

The bond between a mother and daughter can be very strong - in fact, many consider it to be the most powerful, intricate and influential relationship a woman will ever have.

Harmonious one day with the ability to be turbulent the next, the mother-daughter relationship is so complex that daughters often go through life questioning whether there's something wrong with them or with their mothers.

This was certainly the case for Elizabeth Lancaster, author of the new book Marzipan and Magnolias, who wrote of her life facing two obstacles - her complex relationship with her somewhat eccentric mother and the early signs of her own incurable illness, Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

"Marzipan & Magnolias began as small snippets of writing - just paragraphs or scenes - as a way of trying to make sense of a confusing and frightening time in my life," says Elizabeth. "This developed into a series of interlocking stories and gradually it became clear that two themes were dictating the direction of my writing - the complex relationship with my mother and the terrifying neurological episodes I had experienced. These themes ultimately converged and, in the end, I think it is about a struggle for independence.

"Growing up in a family of boys, I knew from a young age, that as the only girl, I enjoyed a special place in my mother's heart. As a child I was curious about her strong atheist views and emotional distance to difficult circumstances. Still, I felt insulated from such distance in my privileged position as her only daughter. So I was unprepared for the barriers which appeared between us when I sought to break away as an adult and establish my own life overseas. When a diagnosis of MS further threatened my independence I simply refused to acknowledge it.

"It was through writing the book that I came to understand my mother better and her strange reactions to difficult situations. I also learnt to come to terms with having MS and also, to some extent, recognise my mother's traits in some of my own responses to situations."

Elizabeth's memoir was selected from more than seventy manuscripts as the winner of the inaugural 2010 Finch Memoir Prize. Selected for its literary quality, Marzipan and Magnolias was applauded by the judges for the author's warm and humorous portrayal of a mother-daughter relationship.

Extract from Marzipan and Magnolias

After dinner, the phone rang. Martin answered it, then spoke to the caller in English, so it was clearly from overseas. I could tell straight away from his voice that something was wrong. He looked at me but it seemed to take forever for him to get the words out.

'It's your mother. Your dad has passed away.'

Even in that protracted moment I was irritated by his use of the euphemism. Why not just say 'died'? But by the time I took the phone, my throat was so tight I couldn't speak. Not that it was necessary as Mum launched in, talking at a million miles an hour.

'It was pneumonia,' she said. 'The old man's friend they used to call it. He didn't suffer. I thought he wasn't right before you left, but I didn't say anything. After all what was the point? He's really been gone for a year, when you think about it and Martin needed you there. But he wasn't right - he died three days after you left …'

'What? When did he die?'

'Three days after you left. Remember I said I wouldn't let you know if something happened. It's been difficult not to tell you and we've had to keep the whole thing quiet in case one of your friends rang you in Germany…'

My mind was as frozen as the wind outside as I tried to calculate precisely how long ago he'd died. So while I'd been answering polite questions from Martin's relatives about my father's health, he was actually already dead. It was as though I'd been existing in some parallel universe.

'What about the funeral?'

'Oh, there's no funeral. He's already been cremated, but I didn't go. None of us did. Dreadful place, the crematorium, evil.

I didn't want to tell you, but Tim said it's getting so long that if I didn't tell you he would.'

I was struggling to process the information.

'Why didn't you let me know sooner?'

'Remember? We talked about this before you left.'

She was right. But we hadn't exactly talked about it; she had simply announced in her most matter of fact tone that if something happened to Dad she wouldn't tell me until I got back. I was used to such comments from Mum. She always said something to that effect before I travelled, even years before when both my parents were fit and well. Other people's mothers might say, 'Make sure you phone straight away if you need anything.' My mother says, 'Just enjoy yourself and I won't bother you if anyone dies while you're away.'

'No, heavens, no. What for? I'm fine.'

She sounded over-amped, like someone on speed. When I hung up Martin asked me what I wanted to do. 'I want to be near the water,' I said.

The kids were already asleep, and Dörte stayed with them while we drove to the ferry wharf. The howl of the wind was so loud we didn't bother trying to talk. I looked out over the black ocean and wondered which direction Australia was from where I was standing. It was literally at the other end of the earth.

That night I felt elated that Dad was free of that place. The indignity had ended. Then the numbness set in. We continued our daily routine of going over to the house and sorting things into boxes but I had the sensation of being contained in a pressure cooker.

I kept telling myself that it was good news, a release for Dad, for all of us after a year of torment. Why did it matter that I hadn't known? Why did it matter that there was no funeral? At night I'd lie awake in bed and wonder that I felt nothing. Nothing except the incessant tingling in my legs. I wondered if that was what a DVT felt like. There'd been lots of press about people developing a deep vein thrombosis on long flights and dropping dead. But I didn't recall tingling being a sign. And surely I wouldn't have one in both legs. But every night there it was, from toes to thighs. The days dragged on. Finally I told Martin I had to go home - it didn't matter that there was no point. I just had to go home.

Elizabeth Lancaster began her working life as an occupational therapist in Australia until she unexpectedly found herself in a writing course in New York, whilst living there with her husband and two children. After she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, writing became essential in her acceptance of and coming to terms with the unpredictable nature of her condition. Since her return to Australia Elizabeth has written for parenting and health magazines on a freelance basis. She lives in Sydney's north with her family.

Marzipan and Magnolias

Finch

Author: Elizabeth Lancaster

ISBN: 978 1921 462 207

Price: $29.95

Interview with Elizabeth Lancaster

Question: Why did you choose to write about the bond between mother and daughter?

Elizabeth Lancaster: It wasn't a conscious decision. I had reached a pivotal moment in my life when many things came together. My father had died and I had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. At the same time, the patterns of secrecy in the relationship with my mother reached a sort of tipping point. I needed to write my way through the issues before I really understood them. In retrospect, it should have been obvious to me that exploring the mother-daughter relationship was the key. I think for women, that relationship is integral to who we are and how we respond to life's unpredictable events.

Question: How much of your inspiration comes from real life and real people?

Elizabeth Lancaster: All the events are from real life. I suppose when writing a memoir, you have to make decisions about focus. It's not possible (or even interesting) to include all events or every character you've ever met, so minor characters are sometimes a compilation of real people to reduce the burden on the reader. However, the main characters are drawn as accurately and faithfully as I can.

Question: There are several issues raised in this book. Was this deliberate or did the story evolve this way?

Elizabeth Lancaster: The story very much evolved that way. I began writing it during a challenging time in my life as a way of processing difficult experiences. At first, I just wrote short bits or scenes and they grew into a series of stories. Gradually it became clear that two themes were emerging: one was the relationship with my mother and the other was coming to grips with my diagnosis of MS. These themes ultimately became entwined and the result for me was an incredibly rewarding journey of discovery.

Question: How does it feel to be the winner of The 2010 Finch Memoir Prize?

Elizabeth Lancaster: Winning this prize has been incredibly exciting. I had never intended to publish this story, however, when I saw the Finch Memoir Prize advertised I couldn't resist entering my manuscript. Perhaps there is something deep within writers that we hope our work will be acknowledged.

Question: What advice do you have for aspiring writers or artists?

Elizabeth Lancaster: Writing is such a solitary pursuit that for me it was important to be part of a writing group. Regular meetings impose a deadline of sorts, and the support and encouragement of the group was invaluable. Listen to feedback with an open mind but remember that in the end you have to trust yourself.

MORE