Kate Daly Cytomegalovirus Interview

Kate Daly Cytomegalovirus Interview

Every day, 1-2 Australian babies are born with a suspected case of CMV. It is passed from mother to baby and is the leading cause of disabilities in infants. This devastating virus has not been widely publicised or discussed by GP's or OBGYNs (something we are now hoping to change), because doctors are powerless to stop the spread of CMV from an infected expectant mother to her unborn baby. These women have no warning about CMV and often the only way they do learn about it, is after giving birth to a severely disabled child.The effects of CMV include deafness, blindness, cerebral palsy, mental and physical disabilities, seizures, and even death.

CSL Limited have announced that it is partnering with the world's largest health research agency, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), to study a potential new treatment for the prevention of congenital CMV infection, one of the most common known causes of congenital (i.e., present at birth) abnormalities in the developed world.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common virus present in saliva, urine, tears, blood and mucus, and is predominantly carried by healthy infants, preschoolers, and children who contract the virus from their peers. Approximately one to two percent of pregnant women are infected with CMV for the first time during their pregnancy, and one in three will pass the CMV infection on to their developing unborn child. The risk of CMV infection is reduced by hand washing and general hygiene.

In Australia, CMV is one of the leading causes of disabilities in infants, including deafness, blindness, cerebral palsy, mental and physical disabilities, seizures, and even death. The symptoms of CMV may not be immediately apparent at birth, and even well beyond. There is currently no proven therapeutic prevention for congenital CMV.

Starting in December, the NIH will initiate a large multi-site clinical trial in the US involving more than 150,000 women to test whether CMV immunoglobulin (antibodies collected from human plasma) is an effective preventative of mother to baby transmission of CMV. CSL is donating product made at its Swiss plant to the NIH for use in this trial as part of its commitment to addressing significant public health issues through collaborative research.

Professor Bill Rawlinson, Senior Medical Virologist at UNSW and CMV expert welcomed the study: "Robust information about prevention of congenital CMV is needed now. One to two babies are born every day with profound medical problems from congenital CMV that might be able to be prevented."

"The commitment by the NIH and CSL to conduct a large study like this will hopefully provide more definitive answers and options for the prevention of mother to baby transmission of CMV."

Dr Andrew Cuthbertson, Chief Scientific Officer of CSL added: "This is a very large, complex and long-term trial that requires the resources of a research agency like the NIH. CSL is very pleased to be able to support this important research, which could ultimately improve pre-natal care around the world."

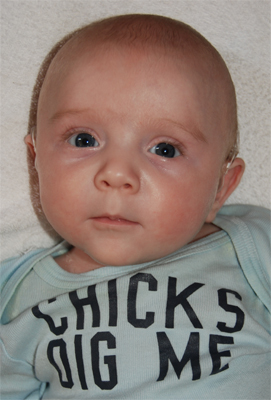

Mother of four children, including twins born with congenital CMV in 2010, Kate Daly was unaware of CMV during her pregnancy but is now very much aware of its impact. Her son William is profoundly deaf and has a significant developmental delay due to congenital CMV. His twin Emmaline has a mild developmental delay due to the virus. "It is great to see an Australian company supporting important research in the area of CMV infection during pregnancy. Women also need to be better educated on steps they can take to avoid contracting the infection themselves, in the first place."

Interview with Kate Daly

Question: Can you explain what Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is?Kate Daly: CMV is a very common virus, particularly in a child care or preschool setting. It is usually harmless with flu like symptoms or no symptoms at all and it generally passes within a few days. Like Glandular fever it is a TORCH virus so once someone has been infected it stays in their body for life and can sometimes be reactivated.

For immune deficient patients, such as those needing transplants, or pregnant women, however, the virus can be very dangerous. CMV is now the most common cause of disabilities from an infection in pregnancy. Approximately 1 in every 160 children in Australia are born with Congenital CMV causing blindness, deafness, cerebral palsy, global development delays, seizures, intellectual disabilities and death. It is the second most common cause of hearing impairment and deafness next to genetics and is more common than both Spina Bifida and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome amongst other things. Approximately 460 children in Australia are born with Congenital CMV every year.

Question: How has CMV directly affected you?

Kate Daly: After my son, a twin, failed his newborn hearing test we were sent to get his hearing assessed by an audiologist at Randwick Children's Hospital. We soon found out that he had permanent moderate to severe hearing impairment and after some tests were done we were told that he had Congenital (meaning present at birth) CMV. Until then, I had never heard of it before. The first year of my twins lives have at times been filled with loneliness, fear, anxiety, worry, guilt, anger, feelings of disconnection as well as sadness to the point of despair at times.

The Doctors told me that I most likely caught CMV for the first time while I was pregnant with the twins since after having it once our body build's a better immunity to it. It is also less likely to cross the placenta and infect your unborn baby if you have had it before. I was told that we had a lot to be hopeful for with William however we were also informed that there was a good possibility that William's hearing would deteriorate and that there was a high risk that he would end up with seizures and developmental delays. The first thing I did when I got home was look up CMV using Google. I was terrified of the vast array of outcomes which taunted William's future. One of the hardest things I have found we have had to live with has been all of the uncertainty. The perfect vision I had of my baby boy growing in to a strong, intelligent young man capable of doing anything he set his mind to was shattered and replaced with a desperate need to know that he won't be too vulnerable, that he will be able to function independently in the busy, competitive society in which we live.

In the last 13 months we have been attending intervention for the hearing impaired and deaf through the Shepherd Centre with visits every few weeks to Australian Hearing for ear mould fittings and to Occupational and Physiotherapy for William's significant global development delays. William has had two Bera hearing tests, a VROA puppet test, about five Cortical tests, a CT scan, blood tests, he's been given grommets, he's had an MRI, four lots of general anesthetics and finally a five hour operation getting Bilateral Cochlear Implants after his hearing deteriorated to profound levels.

Question: What inspired you to start the Congenital CMV Association of Australia?

Kate Daly: When I was told my son had Congenital CMV I will never forget asking about a parent support group and being told that there wasn't one in this country. It flawed me. I ended up being very lucky as I met another CMV Mum through the Shepherd Centre and it was amazing how her friendship and support helped me so that I didn't feel so alone. She understood what I was going through as she had been there before me with her daughter and we bonded instantly with a strong sense of solidarity.

The biggest driving force behind starting CCMV Association of Australia however is that I was absolutely stunned to learn that my son would have to struggle for the rest of his life, that our whole world has been turned upside down and vigorously shaken because of a virus that I could have possibly avoided if I was simply informed about it. Experts say that they believe it is possible for pregnant woman to reduce the number of babies being born with Congenital CMV by half through simple behavioral modifications. That means that every year there is a potential for approximately 230 children to be born free of Congenital CMV. That would mean less cerebral palsy, less hearing and visual impairment, less deafness or blindness, less central processing issues, less autism, less developmental delays, less seizures and intellectual disabilities, less still births, less deaths and less heart break.

The biggest driving force behind starting CCMV Association of Australia however is that I was absolutely stunned to learn that my son would have to struggle for the rest of his life, that our whole world has been turned upside down and vigorously shaken because of a virus that I could have possibly avoided if I was simply informed about it. Experts say that they believe it is possible for pregnant woman to reduce the number of babies being born with Congenital CMV by half through simple behavioral modifications. That means that every year there is a potential for approximately 230 children to be born free of Congenital CMV. That would mean less cerebral palsy, less hearing and visual impairment, less deafness or blindness, less central processing issues, less autism, less developmental delays, less seizures and intellectual disabilities, less still births, less deaths and less heart break.I believe in God and have been brought up to treat others as you wish to be treated yourself. There are no words to express how much I wish someone had informed me about CMV so that I could have tried to protect my unborn children. So now, with the support of my family, that is what I am trying to do for other parents and their unborn children.

Question: What aim do you have for the Congenital CMV Association of Australia?

Kate Daly: The mission statement for CCMV Australia is to provide information and support to the families who have been affected by Congenital CMV, assist experts in the field by supporting Australian research programs, and help minimise and eventually eradicate CMV from Australia through public education initiatives.

Question: Can you talk about how can women avoid contracting the infection?

Kate Daly: Women with children in day care or preschool and their teachers are the highest risk group for CMV infection because the virus is so common in these conditions. Generally speaking CMV can be avoided through simply being more diligent with our own personal hygiene such as hand washing. I would like to really emphasise however that if a pregnant Mum kisses her children on the lips or shares cups, food and cutlery they aren't just risking some added inconvenience to themselves in the way of a simple head cold. They are risking so much more than that. Our children would feel no less love or attention if we gave them extra cuddles and kissed them on the head instead. It wouldn't be at all difficult to make sure we carry antibacterial wipes or gel when at the park to use after wiping our toddlers noses or taking them to a bathroom which doesn't have soap in it. It comes down to some minor modifications, not much when you consider the potential impact CMV can have on an unborn babies life.

MORE