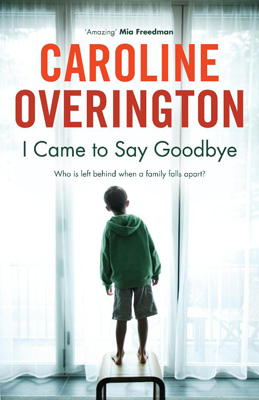

I Came To Say Goodbye

I Came To Say Goodbye

Who is left behind when a family falls apart?

I Came to Say Goodbye is an utterly gripping novel from the bestselling author of Ghost Child. Mental health, child protection, immigration and above all, family drama - I Came to Say Goodbye doesn't shy away from the big issues. You will not be able to put this novel down - it is an extraordinary and unforgettable page turner.

It was four o'clock in the morning.

A young woman pushed through the hospital doors.

Staff would later say they thought the woman was a new mother, returning to her child - and in a way, she was.

She walked into the nursery, where a baby girl lay sleeping. The infant didn't wake when the woman placed her gently in the shopping bag she had brought with her.

There is CCTV footage of what happened next, and most Australians would have seen it, either on the internet or the news.

The woman walked out to the car park, towards an old Corolla. For a moment, she held the child gently against her breast and, with her eyes closed, she smelled her.

She then clipped the infant into the car, got in and drove off.

That is where the footage ends.

It isn't where the story ends, however.

It's not even where the story starts.

Caroline Overington is a two-time Walkley Award-winning journalist who is currently a senior writer and columnist with The Australian. She is the author of two non-fiction books, Only in New York and Kickback which is about the UN oil-for-food scandal in Iraq. Since then she has had her first novel Ghost Child published in October 2009 to great acclaim.

I Came To Say Goodbye

Random House Australia

Author: Caroline Overington

ISBN: 9781742741307

Price: $34.95

Interview with Caroline Overington

Question: How close to the truth, is the storyline of this novel?

Caroline Overington: It is awful for us to admit, but there are many children in Australia who are neglected and abused, and there are many people struggling with a mental illness who cannot get the treatment they need.

It often falls to families - their Mums and Dads, and siblings - to try to help those young people who are mentally ill to make sure they take their medication and get to counselling (if they are, in fact, appropriately diagnosed and treated, which often doesn't happen) and the consequences of not taking mental illness seriously can be dire.

You see the result of it in the courts all the time: earlier this year, a photographer and I embarked on a long journey in the footsteps of a man from Perth who was a paranoid schizophrenic. He had his young son with him, and he killed the boy, with a knife. So yes, of course, reporting in real life informs the story, and that is so very sad.

Question: What research went into I Came To Say Goodbye?

Caroline Overington: I have spent many years reporting on child abuse and child murder for The Australian newspapers, and prior to that, for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald (where, again, one story that stays with me was of a young woman who had given her baby up for adoption, saying she couldn't care for him because of her mental illness. But she was allowed to see him, from time to time. And one day she picked him up from the Mum who had adopted him and drove him to a dam, and killed him. The court case was horrific.)

Over time, I became frustrated with how much of each different story I wasn't able to put in the newspaper. In NSW in particular, there are laws that prevent the public from knowing the truth. So I began writing the truth in novels.

I have in mind a plan to write four books, covering different aspects of children's lives in Australia - the next one concerns the Family Court, and how it handles custody battles - and then I will retire from writing novels, because I will have said everything I want to say.

Question: There are several issues raised in this book, child protection, dysfunctional families and Refugees; was this deliberate or did the story evolve this way?

Caroline Overington: These are real issues for Australians; from time to time, they explode onto the front page, or the ABC will do a long and thoughtful examination, and then it goes away until next time. For people who live with these issues - an ongoing, untreated psychiatric disorder in the family, for example - you are absolutely right, it evolves over time, escalating and growing, breaking up families, putting people under immense pressure, and then, bang. It explodes. I wanted to get that idea across: a slow, smouldering, unfolding disaster is happening to somebody in Australia right now.

Question: How different is writing fiction to the daily non-fiction writing, you do, as a journalist?

Caroline Overington: There is a tremendous amount of freedom. All reporters will tell you this, but one of the main problems we have is `what does the law say?' Because you can have a story that desperately needs to be told, and there might be a law, or a suppression order, that says, no, you can't publish that. One example: the father in Victoria who drowned his children in the dam could not be told in any meaningful way in NSW. Certainly, you could not show the children's faces or use their correct names, or the father's name, or the mother's name - more so because she at first believed him, that it was an accident - and you could give no details that would give away their identity which may even mean things like what state they lived in. As such, we have a system developing in NSW now, where it can be like child murder does not happen. There was a killing recently; it got one line in the paper, one would assume because a relative is involved, and if you name the relative, the child can be identified. These laws are very handy for the government. They are wretched for democracy. So fiction is one way for me to tell the story.

Question: Both of your novels are primarily about child protection, why did you choose to write about this?

MORE