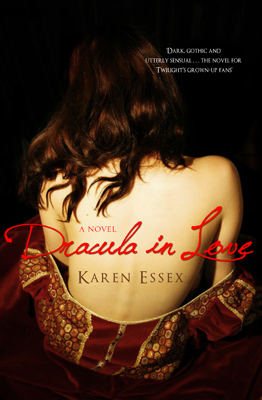

Dracula in Love Interview

Dracula in Love

Reader, you are about to enter a world that exists simultaneous with your own. But be warned: in its realm, there are no rules, and there is certainly no neat formula to become - or to destroy - one who has risen above the human condition ... the truth is, we must fear monsters less and be warier of our own kind.

From the shadowy banks of the River Thames to the wild and windswept Yorkshire coast, Dracula's beautiful, eternal muse, Mina - the most famous woman in vampire lore - vividly recounts the joys and terrors of a passionate affair that has linked her and Count Dracula through the centuries, and her rebellion against her own frightening preternatural powers. Mina's gothic vampire tale is a visceral journey into Victorian England's dimly lit bedrooms, mist-filled cemeteries and terrifying asylum chambers, revealing the dark secrets and mysteries locked within. Time falls away as she is swept into a mythical voyage far beyond mortal comprehension, where she must finally make the decision she has been avoiding for almost a millennium.

The result is a darkly haunting and rapturous tale of eternal love and possession.

Karen Essex is an award-winning novelist, journalist and screenwriter. Her novel, Leonardo's Swans (2006), was a US and international bestseller and it won the prestigious Italian award for foreign fiction, the Premio Roma. Essex has also written two biographies. She has written screenplays for Warner Bros, Columbia/Tristar and 20th Century Fox. Her articles, essays and profiles have been published in Vogue, Playboy, LA Weekly and many other magazines and newspapers. She's made many appearances in the media and is a sought-after guest lecturer at creative writing courses, in history and women's studies programs. She lives in Los Angeles.

Interview with Karen Essex

Question: Most of your previous books have focused on powerful women (countesses, queens)-what was it like instead to turn your talents to an average Victorian-era woman?

Karen Essex: The Mina of Dracula in Love is far from the average Victorian-era woman. In fact, when we meet Mina, she has spent the last fifteen years of her life trying to contain herself into the narrow box of behaviour that was deemed appropriate for the average Victorian woman, and though she has had superficial success, her true self, she finds, will not be denied. Obviously this is true for countless generations of women from time immemorial to the present, but Mina has an even greater challenge. Though she has largely been able to suppress it, she knows that she is unusually gifted and powerful, and that in order to become whole, she must accept these gifts and learn to manage her powers. The Nietzschean quote with which I begin the book is, "You must become who you are."

That is my belief for Mina, for myself, for all of us, whether male of female. Otherwise, a great deal of suffering ensues. On the other hand, to answer your question, the privileged characters in my other books lived, by and large, outside of society's rules, or at least had the money and the power to escape some of those constraints. Mina is not privileged. She is an Irish orphan living in England, trying to assimilate the sort of persona that will yield her a decent life. Traditionally, this is the way it has been for women: play by the rules and we will protect you; step out of line and you will be punished. Mina must choose between protecting herself with her own power and being protected by giving that power up. This story plays out even today in many cultures-subtly in our own culture, and not so subtly in others. For example, the Taliban will protect a woman if she covers herself up and lives in total obedience to their rules.

Question: In Dracula, Mina is a symbol of purity: the classic Victorian "angel in the house." In Dracula in Love, you give her more agency and a passionate nature that was missing in the original iteration. Did you worry about making Mina seem too modern?

Karen Essex: I have been accused in the past of "making" my characters seem to modern, when I wrote about them to begin with because seemed utterly contemporary to me, and I knew they would resonate with modern readers. Though Stoker's text is hyper-misogynistic, he does give Mina a lot of credit. His Mina was the symbol of Victorian purity but she was also a modern woman in that she had learned the skills of stenography and typing, and she surprised his male characters with her ability to assemble information and to use reason and deductive thinking. He brought her along as much as he dared! But his vision of her "purity" and conversely of Lucy Westenra's "wantonness" definitely conformed to the Victorian paradigms for women.

The late Victorian era was a time of tremendous change, and society always responds to radical change with great resistance. This was a challenging era to portray. If you make a cultural study of the 1890s, you find that art, architecture, and design were beginning to look quite modern; in most aspects of life, what we think of as Victorian was giving way to modernity. Feminist thought was everywhere and was a constant topic of discussion in legislative bodies, in the media, and in the home. In reaction to the freedoms and parity women were demanding, "society," or "the patriarchy," or whatever you want to call the keepers of the cultural norm, kept insisting that "good" women were feeble of mind and body and could not handle things like intellectual inquiry, physical exertion, or, God forbid, the vote. At the same time, opportunities for women's education were increasing rapidly because, frankly, they were needed in the exponentially expanding economy and the industrial workforce. Balance this against the fact that women were also being incarcerated in mental institutions for having what we today consider normal sexual desire. It was a time of great paradoxes. I did extensive research in these areas because I wanted to portray women's lives as they would have been at this tumultuous time.

Question: What inspired you to tell Mina's story?

Karen Essex: There were many reasons. I wanted to free the female characters from the good girl /bad girl paradigm and see what happened! I wanted to rebalance the story and tell it in a way that portrayed the reality of women's lives in that era. I also wanted to take the vampire out of the good versus evil religious paradigm he's been trapped in for 113 years. Also, being an historian and a mythology freak, I wanted to explore all the different mythological creatures and the blood-drinkers of history that influenced Stoker's creation of the vampire. It is surprising to many that most of these creatures were female. In the Stoker's (brilliant but) Victorian hands, the victim became the female and the predator the male. This reflected the very real fear of unbridled female sexuality at the end of the 19th century. The vampire became the symbol of the wicked, corrupting male who took the ladies' innocence. In contrast, I wanted to explore and restore the lost landscape of female mystical power to vampire lore.

Question: On your blog, you say that Mina was a very difficult protagonist to write. How did the Mina on the page differ from the one who originally lived in your head?

Karen Essex: Oh, she foiled me from the beginning. She insisted on starting out as a very traditional woman with traditional values and a deep desire for hearth, home, and family. I had no idea that she would begin that way. She is in total opposition to her feminist friend, Kate Reed, who is always trying to get Mina to adapt to the ways of the New Woman. When she first started talking to me, I resisted her. I didn't know her or like her. I thought that Mina would want to be "liberated," but no, she told me that she was in line with Queen Victoria, who did not approve of all this emancipation and thought that suffragettes should get a good spanking! Mina and I battled it out for a while until I realised that I had to let her evolve at her own pace and her own discretion. In the end, she was right and I was wrong. I'm very happy that I capitulated to her will because I think she has a lovely and very satisfying character arc. The poor woman does go through her paces in search of her real self. She realises her power, but man-oh-man, has she paid her dues!

Question: In every era, vampires can be read as representations of other fears. Though they haven't ever really gone away, in recent years they have seen a vast increase in popularity. Do you have a theory about why this is so?

Karen Essex: Vampires used to reflect our fears but now they reflect our fantasies. My theory is that while every generation has longed for a fountain of youth, today we have many youth-extending tools that enable us to reject the very idea of aging. It seems to me that humans today downright abhor the idea of mortality. And who can blame us? We live in a youth-seeking, youth-worshipping society- on steroids. We have stem cell treatments, hormone therapies, cosmetic surgery both invasive and noninvasive, and loads of medicines that can keep us alive past our expiration date. I sometimes run into people who look younger than they looked twenty years ago! We are very close to being vampires already. So the vampires of today are not the monsters who corrupt and destroy, but the magical creatures that provide what we lust for-eternal youth and immortality. We are vampirising ourselves and at the same time, humanising the monsters. For example, the vampires of the Twilight series are "vegetarians," only eating wild beasts and devoting themselves to protecting human life. They are de-fanged, so to speak, and far from losing their immortal souls, have highly evolved consciences. They are not to be feared but emulated.

Question: All of your novels so far have been historical. What is the appeal of the genre for you? Have you ever considered writing a contemporary story?

Karen Essex: I tend to use screenwriting as my outlet for contemporary stories. I am fortunate enough to be able to write historical fiction, and I am even more fortunate in that I love every aspect of the work. I love learning, which is a good thing because I practically get a Ph.D in every era I write about. My great passion, however, is to travel to the actual locations and interact with different cultures. The work is exhaustive, and there is no way I could do it if I were not in love with the process. I have many, many history-based ideas that I have yet to explore in book form. When I run out, I might tackle a contemporary story, but I doubt it.

Question: When you're not writing novels, you're writing or adapting screenplays. What skills from this have you brought over to novel-writing, and vice versa?

Karen Essex: My novels are very cinematic. I'm just rereading my Kleopatra novels, and I am surprised at how cinematic they are. I was not aware of that when I was writing them. The early readers of Dracula in Love tell me that it's very cinematic as well. I do "see" in scenes when I am writing. My editor kept commenting that she loved all the "scene-setting" I was doing. I never actually think about that when I'm writing. I barely "think" about anything at all when I'm writing, to be frank.

I also think that screenwriting has taught me to plot. It's interesting; screenwriting is all about form, so that when I turn to screenplays, I have to let go of my novel-writing tendencies and pay strict attention to plotting, whereas I do believe that bringing a screenwriter's skills to my novels have made them better and more engrossing. Honestly, the process of writing the two mediums is like night and day, using entirely different parts of the brain. Writing a novel is like painting a lavish landscape, and writing a script is like carving a sleek sculpture.

Allen and Unwin

Author: Karen Essex

ISBN: 9781742376134

Price: $24.99

MORE