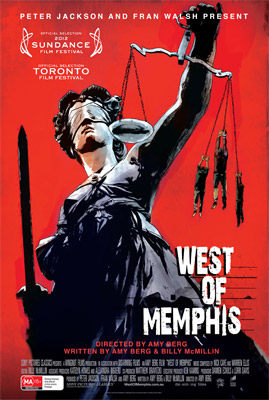

West Of Memphis

West Of Memphis

Cast: Jason Baldwin, Damien Wayne Echols, Jessie MisskelleyDirector: Amy Berg

Genre: Documentary

Rated: MA

Running Time: 147 minutes

Synopsis: Produced by Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, West Of Memphis is a powerful and provocative look into the untold story behind the infamous case of the "West Memphis 3" - three teenagers who were imprisoned for a heinous crime, despite overwhelming evidence of their innocence. Acclaimed filmmaker Amy Berg (Deliver Us from Evil) chronicles their trial, conviction, and the subsequent investigation that generated the movement to prove their innocence, which involved everyone from grassroots supporters to celebrated artists and musicians. The film features original music by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis.

Release Date: February 14th, 2013

Director's Statement

In 2007, I received a phone call from a friend, asking if she could give my phone number toPeter Jackson and Fran Walsh because they wanted to discuss a project with me. At the time, I didn't know much about the West Memphis Three. When I learned that the story of this case had become so important to Fran and Peter that they wanted to produce a documentary about the crime and subsequent legal battle, I wondered what could have moved this pair of successful filmmakers who lived eight thousand miles away from Arkansas to be so invested in seeing the West Memphis Three walk free from prison. But after our first conversation-hearing the unwavering commitment in their voices as they spoke about the case; about the 18 years of injustice, an investigation rife with corruption, and the destruction of multiple lives-I understood that this was a story that not only exposed a frightening failure of justice within our legal system, but exposed a judicial culture where innocence did not matter.

Soon after that conversation, I met Lorri Davis, the wife of Damien Echols. Lorri and Damien had been together for 15 years, married for twelve of them, yet had never shared a life together that did not involve prison bars, and shackles; a life of having to say goodbye every time they met. We spoke for hours; I heard about the promising developments and outrageous disappointments that they had lived through, day after day, and year after year. After I met Lorri and Damien in person, and experienced first-hand their strength of character, poise, and love for each other I knew I wanted to make this film.

Soon after that conversation, I met Lorri Davis, the wife of Damien Echols. Lorri and Damien had been together for 15 years, married for twelve of them, yet had never shared a life together that did not involve prison bars, and shackles; a life of having to say goodbye every time they met. We spoke for hours; I heard about the promising developments and outrageous disappointments that they had lived through, day after day, and year after year. After I met Lorri and Damien in person, and experienced first-hand their strength of character, poise, and love for each other I knew I wanted to make this film. Much of my career has been devoted to the plight of all victims of the judicial system. The families of murder victims and the wrongly incarcerated both suffer from the same corruption that is endemic to the very institutions they look to for guidance and protection. Rarely had I come across a failure of justice with such profound consequences - three young men falsely convicted of crimes for which they were still imprisoned; six families lives forever destroyed while the real killer of three eight year old boys remained free. A combination of poverty, corruption, political ambition and religious bigotry had collided in this case to create a horrific illustration of how wrong things can go for everyone when we, as a society, fail to do all in our power to discover the truth.

I spent over two years chasing down every lead, every person willing to talk to us, pulling at the tangled threads of the truth to see where it might lead. This film is the end result of that journey.

The day after I left Memphis, a friend and prominent figure in the US justice system told me about a phrase that's been coined to describe how the legal community operates in corrupted judicial systems: "Just Us" … The term encapsulates the idea that rather than an equable court of justice, there are only the authorities who control that system. To me, the phrase eloquently summarises the long series of omissions and outright manipulations that characterised this case for so many years. But the phrase can also be flipped around. Damien, Jason and Jessie took the power from the state to successfully broadcast the facts of their innocence. They became the "us." It has been a source of great pride and gratitude to me to be able to share in the process of three, young, innocent men, supported by thousands of well-wishers from all over the world, taking the judicial system back. West of Memphis shows how "Just Us" can transform into All of Us; all those who refuse to surrender to injustice, regardless of what higher authorities might like us to accept.

- Amy Berg, January 2012

About The Production

Sometimes the trigger to action is inaction. In 2005, when Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh first became aware of the inadequacies and outright injustices of the legal proceedings that brought Damien Echols to death row in 1994, what shocked them was that the case had languished since his conviction. The combination of human error and politicised decision-making that built the case against Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley Jr. for the murders of three young boys in rural Arkansas is frighteningly prevalent. But one distinguishing point of the notorious "West Memphis 3" case was the volume of conflicting evidence that was publicly available, yet had made no impact on the fate of the three young men incarcerated for a terrible, still unsolved crime. "The more court documents we read," Fran Walsh recalls, "the more dreadful it all became, and the natural hope was that the three were about to get out soon. But, in fact, nothing was happening. That 'nothing" was the catalyst that moved us to contact Lorri Davis." Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh began an intense correspondence with Lorri Davis, who brought them up to date on the case-and made sure that Damien Echols himself was an integral part of the process from the beginning. At the end of 2005, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh met Lorri Davis along with attorney Dennis Riordan in New York City. Each additional layer of information on the trial that resulted in life sentences for Jason Baldwin and Jessie Miskelley, and a death sentence for Damien Echols, further persuaded Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh that justice had not been served. Since the deeply troubling findings that were already readily available had not influenced the position of the State of Arkansas on the guilt of the three young men, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh decided to launch an investigation of their own. It was clear to them that hard science had been sorely neglected in the case. And this omission became their starting point. By pursuing DNA evidence and an objective reexamination of the forensic evidence that had been gathered in the original trials, they hoped to clarify what had actually happened to the three, eight-year-old boys whose bodies had been discovered in a grisly condition at the bottom of a creek.

Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh began an intense correspondence with Lorri Davis, who brought them up to date on the case-and made sure that Damien Echols himself was an integral part of the process from the beginning. At the end of 2005, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh met Lorri Davis along with attorney Dennis Riordan in New York City. Each additional layer of information on the trial that resulted in life sentences for Jason Baldwin and Jessie Miskelley, and a death sentence for Damien Echols, further persuaded Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh that justice had not been served. Since the deeply troubling findings that were already readily available had not influenced the position of the State of Arkansas on the guilt of the three young men, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh decided to launch an investigation of their own. It was clear to them that hard science had been sorely neglected in the case. And this omission became their starting point. By pursuing DNA evidence and an objective reexamination of the forensic evidence that had been gathered in the original trials, they hoped to clarify what had actually happened to the three, eight-year-old boys whose bodies had been discovered in a grisly condition at the bottom of a creek. For Lorri Davis, the decision by Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh to fund a fresh investigation that would begin at the start of 2006 offered a glimmer of hope. For the first time since she herself became involved with Damien Echols' legal case in 1998, there was a real strategy in place to begin constructing the foundation for a challenge to the convictions. Moreover, with almost all of Damien Echols' avenues of appeal exhausted, the DNA appeal had become one of his last bids to escape execution. Every day, there was work to be done and there were fresh developments to be parsed. It was an immensely complex process, as Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh were to discover, since it was always, necessarily, an investigation, not of one, but of three cases: that of Jason Baldwin and Jessie Miskelley, as well as of Damien Echols.

For Damien Echols himself, the idea of embracing the new private investigation as grounds for hope was more fraught. Worn out from having to live the case every single day for years, he had learned not to think about the evolving status of the case. "I'd had my hopes picked up and let down so many times," Damien Echols recalls. "If you let that keep happening, it kills something in you." But he was grateful for the copious supply of books and magazines that Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson sent him- precisely because they distracted him from his own plight. Reading gave him a window onto the outside world.

Throughout 2006 and well into 2007, all efforts were concentrated on carrying out the methodical, exacting forensic science analyses that had been dispensed with in the mash up of sensationalism and political expediency that defined the initial trial. Private investigators hired by Walsh and Jackson gathered multiple DNA samples from key sites and individuals, then presented these findings to SERI, one of the most highly regarded independent DNA experts in the field. They submitted the physical evidence-most notably the numerous disturbing photographs of the boys' mutilated bodies- to Dr. Werner Spitz, Dr. Michael Baden, Dr. Janice Ophoven, Dr. Terry Haddix, Dr. Richard Souviron, Dr. Vincent Di Maio, Dr. Robert Wood, top pathologists and odontologists, to determine whether their interpretations matched those of Frank Peretti, the local medical examiner who'd testified in court on behalf of the prosecution about their significance.

In May of 2007, revelations began to roll in that completely transformed the profile of the case. Expert pathologists all arrived independently at identical, unequivocal conclusions: the wounds and mutilations that disfigured the bodies of the boys to such viscerally horrifying effect- injuries that had been instrumental in convincing the jury to give Damien Echols a death sentence-were not caused by a knife. Nor had they occurred in the midst of a satanic ritual preceding the murders. The gory injuries were caused by animal predation-post-mortem bites to the bodies as they lay underwater. Frank Peretti's qualifications-he was an assistant medical examiner who was not even board certified at the time of the trial-now seemed woefully insufficient. He was literally out of his depth.

But it wasn't only the radical reappraisal of the victim's injuries that occurred that year. In early 2007 the DNA findings began to arrive. None of the DNA of either Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin or Jessie Miskelley was found on any of the physical evidence connected to the murders. Just as dramatically, DNA found on a hair underneath a ligature that had been used to bind one of the boys matched that of Terry Hobbs, the stepfather of one of the murdered children.

Inexplicably given his own legal history, Terry Hobbs had never been interviewed by the police, nor had his home been searched.

The watershed year of 2007 convinced Fran Walsh, Peter Jackson and Lorri Davis that a new trial would be granted to the West Memphis 3. In September of 2008, the new evidence, which went beyond the pathologists' reports and the DNA findings to include juror misconduct and other irregularities, was presented to Judge David Burnett, who'd presided over the original trial.

David Burnett dismissed the new evidence out of hand, saying that it was not compelling enough to warrant a new trial.

Damien Echols moved one step closer to execution. This blanket dismissal of a substantial dossier of evidence casting grave doubts over the first trial was one of the low points for Damien Echols throughout the entire ordeal. Fran Walsh, Peter Jackson and Lorri Davis, meanwhile, were appalled at the notion that the wealth of new information appeared utterly irrelevant in the eyes of the court.

This was the moment when the idea of creating a film on the case was conceived. "We felt there had to be a way to make the greater public aware of what was happening in this case," Fran Walsh recounts. "There were no other documentaries in production. There wasn't much public interest. It was a dead time. We were determined to get the information out, and we came up with the idea of presenting the evidence in a film, to let the public would know what was being done in their name. Getting the true story into the public arena seemed our best hope for pressuring the authorities to reassessing the case. We mooted the idea with Damien Echols and Lorri Davis."

Damien Echols and Lorri Davis were immediately, wholeheartedly on board. By this point, Damien Echols was eager to speak with anyone he could. He felt he had nothing to hide, and the court would listen to nothing his supporters uncovered that further bolstered his claim to be innocent. Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson reached out to filmmaker Amy Berg, whose film Deliver Us From Evil convinced them that Amy Berg had the courage and tenacity to go into Arkansas and tackle the story. They had seen defense attorneys and others get tattered in the process of trying to salvage the facts in this case. They knew that the director for this project would need to be someone who was not only capable of making a great film, but also someone who could grasp the intricacies of how the film would play a key role in the defense.

Amy Berg was unfamiliar with the story of the West Memphis 3 when the project was first proposed to her, but over the course of a couple of months of back and forth with Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson, she began to immerse herself in all the evidence and coverage the case had received. She hesitated at first about taking on the film because she recognised what a massive project it would end up being. But then she met Lorri Davis and found herself enormously moved by her account of events in the story. She then spoke with Damien Echols on the phone and found him to be an extraordinary presence. One of the first things he told her was that he wouldn't give up a single day he'd spent on death row since that experience had, in fact, made him who he was. Amy Berg travelled to Arkansas to visit Damien Echols in prison. They spoke for three and a half hours about everything from life and literature to spirituality. Damien Echols told her that he would meditate for up to seven hours a day to retain his sanity in that torturous prison environment. The idea of the discipline it required to sustain that kind of focus in a 90 square foot room with no natural light astonished her.

Amy Berg was unfamiliar with the story of the West Memphis 3 when the project was first proposed to her, but over the course of a couple of months of back and forth with Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson, she began to immerse herself in all the evidence and coverage the case had received. She hesitated at first about taking on the film because she recognised what a massive project it would end up being. But then she met Lorri Davis and found herself enormously moved by her account of events in the story. She then spoke with Damien Echols on the phone and found him to be an extraordinary presence. One of the first things he told her was that he wouldn't give up a single day he'd spent on death row since that experience had, in fact, made him who he was. Amy Berg travelled to Arkansas to visit Damien Echols in prison. They spoke for three and a half hours about everything from life and literature to spirituality. Damien Echols told her that he would meditate for up to seven hours a day to retain his sanity in that torturous prison environment. The idea of the discipline it required to sustain that kind of focus in a 90 square foot room with no natural light astonished her. It had been ten years since Damien Echols had been the subject of documentarian attention. There'd been no communication with other filmmakers during that decade.

"My approach is different from that of a lot of other documentary filmmakers," Amy Berg notes. "I feel I can create a much stronger film when I have a greater understanding and trust with my subjects. I have to be emotionally moved myself in order to create work that will move others. I was committed from the start to presenting all the many aspects of this complex story-including the perspectives of all the relevant authorities, even when I believed their interpretation of events was refuted by the evidence. It was clear to me that this story had become a tragedy for everyone involved."

But working on the film also became a lifeline of hope for Lorri Davis and Damien Echols. "As producers on the film," Damien Echols says, "West of Memphis became the very first time we were given the chance to tell our own story. In the case of every other production-whether it was for television or a movie-the story was ultimately fulfilling someone else's agenda and was shaped the way they wanted to shape it. But Amy Berg, Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson gave us the chance to let this film become the truth we lived. That makes its' vision unique."

From the start of the project, the fact that the film was enmeshed with the defense also created singular constraints. There was information that had to be protected since once it was released it could be subpoenaed by the state. New rounds of interviews with witnesses began to produce an astonishing series of recantations of testimony. Yet there were confidentiality agreements that had to be observed and which forestalled the possibility for a premature disclosure of the full story. "The case always came first," Fran Walsh remarks. "We had a responsibility to the defense, we were privy to sensitive and confidential information and we had to respect that, but getting the truth about the case into a public forum was always our long term goal."

At last, however, the momentum toward a reversal of the 1994 verdict began to build. In August of 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court granted Dennis Riordan's petition for a new evidentiary hearing. The oral arguments were heard in September of 2010. Prior to that, at the end of August, Eddie Vedder held a press conference and benefit concert in Arkansas on behalf of the West Memphis 3, and national and international media returned to the state in full force to cover the story. On November 4th, 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court unanimously overturned all points in Judge David Burnett's DNA ruling.

"For the first time," Damien Echols says, "I began to feel hope again. It wasn't just one thing. I knew the physical evidence wouldn't be sufficient to free me. It was a combination of everything. I'd always known that one day I would win my freedom. It may be a naïve belief, but I didn't think the victory of the good guy was just something you saw on television-I was convinced that good eventually prevails in real life as well."

In point of fact, the new Supreme Court-ordered hearing would be repeatedly postponed. In order to save face-and protect itself from the possibility of a costly suit for wrongful imprisonment- in August of 2011 the State of Arkansas agreed that the Memphis 3 would accept the highly unusual Alford plea whereby the defendants could simultaneously assert their innocence while pleading guilty in their own best interest. On August 19, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley accepted the pleas proposed by Judge David Lazer and were released from prison. The gross miscarriage of justice that put three teenagers behind bars for eighteen years has brought no repercussions for the State of Arkansas and the killer of the three eight-year-old boys remains at large.

West Of Memphis Timeline

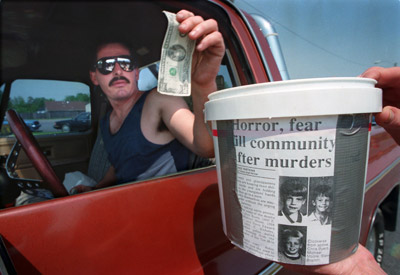

West Of Memphis TimelineMay 1993: Three eight-year-old boys-Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and ChristopherByers-are found dead in a creek in Robin Hood Hills, West Memphis, Arkansas.

February 1994: Jessie Misskelley is convicted of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder

March 1994: Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin are found guilty on three counts of murder.Echols is sentenced to death and Baldwin to life in prison.

August 1996: Lorri Davis meets Damien Echols for the first time in person.

December 1999: Lorri Davis and Damien Echols get married

2005: Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh begin speaking with Lorri Davis, offering to help in any way they can.

December 2005: Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh meet with Lorri Davis in New York City. Lorri Davis catches Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh up to speed on the case's latest developments.

2006: A strategy is put in place to construct the foundation for a new challenge to the convictions. Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh officially begin working with the defense team, funding defense investigation anonymously.

May 2007: New key evidence and shocking revelations are uncovered that go beyond the pathologists' reports and the DNA findings to include juror misconduct and other irregularities.

November 2007: The defense holds a press conference to publicise the new DNA and forensic findings.

September 2008: The new evidence is presented to Judge David Burnett, who had presided over the original WM3 trial. Judge Burnett dismisses the new evidence saying it is not compelling.

2008: The WM3 case is stagnant. Public and media interest seems to have disintegrated.

2008: The WM3 case is stagnant. Public and media interest seems to have disintegrated.2008: Lorri Davis and Fran Walsh contact filmmaker Amy Berg with the thought of creating an investigative documentary to present new findings.

2008 Amy Berg travels to Arkansas to speak with Damien Echols and Lorri Davis. She works tirelessly for two years immersing herself in the case, interviewing sources, and documenting the defense's investigative efforts. No media or film crews are on the ground.

August 2010: Eddie Vedder and other high profile celebrities host a benefit concert for the WM3. At this point, national and international media return to cover the case. This same month, the Arkansas Supreme Court grants Dennis Reardon's petition for a new evidentiary hearing.

September 2010: Oral arguments are heard.

November 2010: The Arkansas Supreme Court unanimously overturns all points in Judge David Burnett's initial ruling.

August 2011: The State of Arkansas agrees to accept the Alford Plea whereby the defendants could simultaneously assert their innocent while pleading guilty in their own best interest. Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, Jessie Misskelley accept the pleas and are released from prison.

MORE