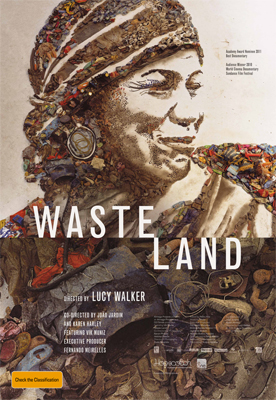

Waste Land

Waste Land

Cast: Vik MunizDirector: Lucy Walker

Genre: Documentary

Running Time: 98 minutes

Synopsis: Filmed over nearly three years, Waste Land follows renowned artist Vik Muniz as he journeys from his home base in Brooklyn to his native Brazil and the world's largest garbage dump, Jardim Gramacho, located on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. There he photographs an eclectic band of "catadores" - or self-designated pickers of recyclable materials. Vik Muniz's initial objective was to "paint" the catadores with garbage. However, his collaboration with these inspiring characters as they recreate photographic images of themselves out of garbage reveals both dignity and despair as the catadores begin to re-imagine their lives. Walker (Devil's Playground, Blindsight) has great access to the entire process and, in the end, offers stirring evidence of the transformative power of art and the alchemy of the human spirit.

Release Date: December 1st, 2011

Production Notes

'The moment when one thing turns into another is the most beautiful moment. A combination of

sounds turns into music. And that applies to everything'

Vik Muniz 'Waste Land'

'What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.'

T.S. Eliot 'The Waste Land'

Directors Statement

I have always been interested in garbage. What it says about us. What in there embarrasses us, and what we can't bear to part with. Where it goes and how much of it there is. How it endures. What it might be like to work with it every day. I read about one woman's crusade to show her appreciation for all the sanitation workers in New York by hugging each of them, and I applauded the sentiment and yet ... there had to be some other way for me to show my appreciation.

Then when I was a graduate film student at NYU, I started training with the NYU Triathlon Club. As we endured the most grueling 6:00 a.m. workouts imaginable, I bonded with fellow triathlete Robin Nagle, a brilliant professor who was teaching about garbage. Listening to Robin Nagle talk about her work was so fascinating that I began sitting in on her PhD seminar, and loved deepening my thinking about the sociology and implications and revelations and actuality of garbage.

So when Robin Nagle took her grad students to visit Fresh Kills, the landfill in Staten Island, I was curious and gatecrashed. These days it is best known as the resting place of the debris from the World Trade Center, but this was back in March 2000. It was a shocking place, with chainlink fences clad with teeming nightmare quantities of plastic bags making the nastiest noise imaginable, and pipes outgassing methane poking up at regular intervals through the exaggerated contours of the grassedover giant mounds of garbage. It's a parody of an idyllic hyper-landscaped city park, with garbage hills 225' high - taller than the Statue of Liberty. We looked at the rats and seagulls and dogs, and at the palimpsests of layer upon layer discarded possessions. And we tried to ignore the putrid smell.

I love great locations in movies, and I couldn't believe I'd never seen a landfill on-screen before. It was the most haunting place. And all of the garbage I'd ever generated living in New York City was in there somewhere. This was the graveyard of all my stuff. Along with everyone else's. I immediately knew that I wanted to make a movie in a garbage dump.

Cut to 2006, and I met producer Angus Aynsley and co-producer Peter Martin at BritDoc and again at the London Film Festival, and instantly liked them enormously and wanted to work with them. Talking about possible projects, Angus mentioned that he had met Vik Muniz and been impressed by his highly entertaining slideshow about art history. I had seen and loved Vik Muniz's work, and I was hugely excited about the possibility of working with him. So I read some of Vik Muniz's writing and set off with Angus and Peter to meet Vik Muniz in Newcastle, England when he had an opening at the Baltic in January 2007.

When we met up again in Vik Muniz's studio in New York two months later the conversation turned to garbage, and I suddenly thought about my trip to Fresh Kills seven years previously. That was the lightbulb moment. Vik Muniz had previously done a beautiful series using junk, and he had also done projects with street sweepings and dust. His creative use of materials is his signature - whether chocolate sauce, sugar, or condensation trails from planes -- so this project would very much be an extension of his earlier work. After we'd started talking about it, no other ideas were interesting anymore. I knew that a collaboration between Vik Muniz and the catadores would be potentially very dramatic. Vik Muniz had previously done some brilliant social projects with street kids in Sao Paolo and had a wonderful ongoing project in Rio which employed kids from the favelas, and I was totally inspired by him.

When we met up again in Vik Muniz's studio in New York two months later the conversation turned to garbage, and I suddenly thought about my trip to Fresh Kills seven years previously. That was the lightbulb moment. Vik Muniz had previously done a beautiful series using junk, and he had also done projects with street sweepings and dust. His creative use of materials is his signature - whether chocolate sauce, sugar, or condensation trails from planes -- so this project would very much be an extension of his earlier work. After we'd started talking about it, no other ideas were interesting anymore. I knew that a collaboration between Vik Muniz and the catadores would be potentially very dramatic. Vik Muniz had previously done some brilliant social projects with street kids in Sao Paolo and had a wonderful ongoing project in Rio which employed kids from the favelas, and I was totally inspired by him. A month later, Angus Aynsley and I got exciting news that Fabio had found one landfill where the drug traffic was under control, and the catadores were being organized into a co-operative by a charismatic young leader who might be open to collaborating with Vik Muniz. We were all very nervous - there were so many things to be afraid of, from dengue fever to kidnapping - but we all wanted to go. We arrived in Rio de Janeiro in August 2007 - Vik Muniz, Angus Aynsley, Peter and I. Seeing the extremes of poverty and wealth so ostentatiously displayed through the car window the contrasts of mountains and oceans, black and white, garbage and art, art stars and catadore ... the contrasts couldn't be more starkly drawn than in Rio de Janeiro, and I realized that it wasn't a coincidence that we were tackling this particular topic in Rio. It was perfect.

For me this film, as with all of my work, is about getting to know people who you do not normally meet in your life. And, if I'm doing my job, I aim to create an opportunity for the audience to feel they are getting under the skin, to emotionally connect with the people on the screen. But you need people you can care about. And so when Valter first cycled into my line of sight, I knew for sure that we had a movie. That day I had gone on my first recce to the landfill and was dressed head-to-toe in protective layers fit for a moon landing. His bike was decorated so creatively with odd trinkets from the trash and he honked his eagle horn with such sweet wit that I was totally smitten.

I am Vik Muniz's biggest fan. And this idea of "the human factor", about scales in portraiture, and distances in getting to know people, is what the movie is about, for me. I'm not sure anyone will notice this unless I tell them, but there are three references to ants in the movie: Vik Muniz says that when he is flying over Gramacho, the people look like "just little ants, doing what they do every day"; then Isis talks about the ant that she saw crawling over her dead son's face; finally we see Vik Muniz playing with an ant with his paintbrush in the studio. That play of being so far away that people are just ants, with no "human factor" is the opposite experience of being so deeply connected to your son that you will never forget "not the tiniest detail, not a single single detail", not even an ant on his face in a single moment.

And Vik Muniz, as an artist, plays between these levels of proximity and distance, between showing the viewer the material and showing them the idea, revealing the relationship between the paintstrokes and the scene depicted by the paint. The portrait is Isis, it is a Picasso, it is a bunch of garbage, and it is a work by Vik Muniz - all at once. You can view things close in or further away. Likewise you can fear people from afar or you can go interact with them. I love the Eames's Powers Of Ten and I wanted to create a social analog. To start with we see the place from GoogleEarth, then from a helicopter, then from a car, then from a safe distance, then from a first meeting, then from a growing friendship, then from it having changed you fundamentally and permanently.

Just as Vik Muniz wants the portraits to serve as a mirror in which the catadores may see themselves, so I hope the movie serves as a means for us to see our journey to becoming involved with people so far from ourselves. To zoom all the way in to caring about someone who was previously as far away as it's possible to be.

Questions poke through the fabric of the movie as things get messy. In Waste Land Vik Muniz and his wife start to argue on-camera about whether the project is hurting the catadores by taking them out of their environment and then, when it's over, expecting them to return. Likewise, should documentary filmmakers interfere with their subjects' lives? But how could they not? I don't believe in objectivity. I observe the observer's paradox every moment I'm filming. Your presence is changing everything; there's no mistaking it. And you have a responsibility.

My heartfelt thanks to the catadores. I can't help seeing Waste Land as the third in a triptych with my earlier films Devil's Playground and Blindsight, and not least in the awe and gratitude I feel for the group of people who were courageous enough to share their stories with us -- and to live lives so rich in inspiration for us all. We dedicate the movie to Valter, and remember him saying that 99 is not 100. A single can, or a single catador, can make the difference.

Lucy Walker, January 2010

Director's Blog from Location at the Largest Garage Dump in the World, Jardim Gramacho - August 2007

Just when you get used to the smell they find a human body, or mention a leprosy epidemic, and the sound man passes out. But at least it's at sea level - after the hell of 23,000' for Blindsight I'm relieved to look across at the ocean at all times.

Across the bay you can see Christ The Redeemer reaching his arms out to the wealthy in Rio's south zone - Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon. They say even Christ turns his back on the north of Rio, where we are.

Don't worry, we have kidnap insurance, the producers tell me - from their desks on Ipanema beach. But seriously, everyone is wonderful. O2 Filmes, and Vik Muniz, the fantastico Brazillian artist who got me into all this, and our crew - our sound man's dad wrote Pixote, one of my favorite movies, and especially our producer Angus Aynsley. It's the most enjoyable shoot, notwithstanding the garbage. Vik Muniz describes Rio as St. Tropez surrounded by Mogadishu. The garbage is the only place in Rio where the social extremes get mixed in together. The posh rubbish from the south zone with the cheap trash from the favelas. Garbage is the negative of consumer culture, it's everything that nobody wants, and when it disappears from everyone's lives, rich or poor, it doesn't disappear at all, it appears here, like a conjuring trick gone wrong.

Garbage is a matter of opinion, say the catadores who work here, sifting through. Tread carefully, because you are treading on money. On a bad day they make twice minimum wage salvaging cans, bottles, plastics, paper. Then somebody finds R$30,000 cash - while somebody else finds two headless bodies. After Carnival they pick out the discarded costumes and wear them as they work.

When the airline Varig did a dump everyone dressed up in the air steward outfits and served each other recycled drink bottles.

That's the most striking thing, the good humor, the sheer fun. These people are having a good time. When we film The Governor, a grinning old-timer with a boombox strapped to his belly - he calls out"I'm gonna be on TV". "Yeah, the animal channel", comes right back.

And they are honest. They don't touch each other's piles of pickings. Many catadores had limited career choices: prostitution, drug traffic, or garbage, and they chose garbage, where the only person you hurt is yourself. There is a lot of pride.

Zumbi is the resident intellectual. We hear about him before we see him - we hear that when he sees a book, he doesn't see just recycling paper. He has kept every book he's ever found on the landfill, and he has a lending library in his shack. He's handsome, like a young Sam Jackson, with a white towel tied around his head and a paperback bulging in his shorts.

Half of the catadores sleep in the garbage, risking being run over by trucks, and the other half sleep in the worst favela in town. Their garbage-clad open-sewer favela makes the other favelas look like the Amalfi coast, with their brightly-coloured two-story buildings with twinkling christmas lights piled up the hillside.

Evenings we return to the south zone. I sulk as I head to a delicious dinner in a bulletproof car, I'd rather be with the catadores than these billionaires moaning about the price of contemporary art. How competitive the current art market is, because there is just so much money, you have to interview and practically beg for the chance to buy insanely overpriced art works by totally unestablished artists. These are the people who are going to buy the art work that Vik is making in the garbage in our charity auction at Phillips. And these are the people whose garbage will be part of the piece. We're going to trace all these comings-and-goings of things.

Evenings we return to the south zone. I sulk as I head to a delicious dinner in a bulletproof car, I'd rather be with the catadores than these billionaires moaning about the price of contemporary art. How competitive the current art market is, because there is just so much money, you have to interview and practically beg for the chance to buy insanely overpriced art works by totally unestablished artists. These are the people who are going to buy the art work that Vik is making in the garbage in our charity auction at Phillips. And these are the people whose garbage will be part of the piece. We're going to trace all these comings-and-goings of things. When we ask the catadores what they want to do with the money from the auction, they say they're not sure, their first thought is that they don't really need anything, They have everything they need. Richer people are much quicker to tell you what they need money for. I guess the catadores know exactly where most things that people spend money on wind up.

Artist Background

Brazilian-born, Brooklyn-based illusionist and innovator Vik Muniz lives for the moment when all of our fixed preconceptions fail us and we are forced to enter a dialogue with the world we inhabit. In this moment, we are confronted with the chaos that is otherwise hidden from view. It is precisely through his art work (both in product and process) that Muniz harnesses the generative possibility of chaos. Similar to dumpster diving and freeganism, Vik Muniz's latest project "Pictures of Garbage" is invested in the excavation of garbage. However, a key distinction is that his particular exploration moves beyond questions of utility- he isn't simply interested in finding and salvaging the secret treasures within trash heaps (ipods, sealed fruit bowls, jewelry) but rather in using garbage as an art medium.

"The beautiful thing about garbage is that it's negative; it's something that you don't use anymore; it's what you don't want to see," says Vik Muniz. "So, if you are a visual artist, it becomes a very interesting material to work with because it's the most nonvisual of materials. You are working with something that you usually try to hide."

First, Vik Muniz traveled to the biggest garbage dump in the world, Jardim Gramacho (north of Rio de Janeiro) where he was met with a community of people who scavenge the recyclable refuse of the city - catadores in Portuguese - to make a living. An estimated 3,000-5,000 people live in the dump, 15,000 derive their income from activities related to it, and some that Muniz met in Jardim Gramacho come from families that had been working there for three generations. Catadores like the trash heaps they call home, are shunted to the margins of society and made invisible to the average Brazilian. And yet, Vik Muniz is not interested in perpetuating a "Save The Children" politics of pity that positions catadores as passive victims. "These people are at the other end of consumer culture," he says. "I was expecting to see people who were beaten and broken, but they were survivors." Vik Muniz quickly befriended and collaborated with a number of catadores on large-scale portraits of themselves including Irma, a cook who sells food in the dump; Zumbi, the resident intellectual who has held onto every book he's scavenged; and 18-year-old Suelem, who first arrived there when she was 7.

According to Donald Eubank, "Vik Muniz rented 4 tons of junk and a warehouse, and together they arranged the trash on the ground to replicate photographs of themselves that Vik Muniz had taken earlier. Then they would climb up to the ceiling and take photos of the compositions from 22 meters high. The portraits of the people are made out of empty spaces, out of what wasn't garbage". Calling upon his resources as a world famous artist, Vik Muniz raised $64,097 at the esteemed Phillipe de Pury auction in London by selling one of his garbage portraits. 100% of the profits went to the Garbage Pickers Association of Jardim Gramacho.

Jardim Gramacho

Built on the north edge of Rio de Janeiro's Guanabara Bay directly across from the iconic statue of Christ the Redeemer, whose back is turned to it, arms outstretched away towards the south, the metropolitan landfill of Jardim Gramacho ("Gramacho Gardens") receives more trash every day than any landfill in the world. 7,000 tonnes of garbage arriving daily make up 70% of the trash produced by Rio de Janeiro and surrounding areas.

Established in 1970 as a sanitary waste facility, the landfill became home to an anarchic community of scavengers during the economic crises of the 70's and 80's. These catadores lived and worked in the garbage, collecting and selling scrap metal and recyclable materials. They established a squatter community (the favela of Jardim Gramacho) surrounding the landfill that is now home to over 20,000 people and entirely dependent on an economy that revolves around the trade of recyclable materials. In 1995, Rio's sanitation department began to rehabilitate the landfill and formalize the job of the catador, granting licenses to catadores as well as enforcing basic safety standards, like the prohibition of children from the landfill. They also began a pilot project to create a carbon negative power plant fuelled by urban solid waste. On the other hand (ON THEIR SIDE), the catadores formed ACAMJG, the Association of Pickers of Jardim Gramacho, whose president TiĆ£o Santos is featured in WASTE LAND. ACAMJG lead the way in community development. With (UNDER) Mr. Santos' leadership, ACAMJG has created a decentralized system of recycling collection in neighboring municipalities; the creation of a recycling center, professional recognition of the catador, enabling catadores to be contracted for their services, the creation of a 24 hour medical clinic, and the construction of a daycare center and skills training center. In addition to their community initiatives, ACAMJG leads a national movement for greater professional recognition for the catador and support from the federal government and has teamed up with other movements across South America to hold the first international conference of catadores in SĆ£o Paulo in November 2009.

Today roughly 1,300 catadores work in the landfill each day, removing 200 tonnes of recyclable materials each day. They have extended the life of the landfill by removing materials that would have otherwise been buried and have contributed to the landfill having one of the highest recycling rates in the world. The landfill is scheduled to close in 2012 and groups like ACAMJG are fighting to raise support to provide skills training to catadores. Information on how to help and give donations to ACAMJG and the catadores can be found on our website.

Vik Muniz was born into a working class family in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1961. As a young man he was shot in the leg whilst trying to break up a fight. He received compensation for his injuries and used this money to fund a trip to New York City, where he has lived and worked since the late 1980s. He began his career as a sculptor but gradually became more interested in photographic reproductions of his work, eventually turning his attention exclusively to photography. He incorporates a multiplicity of unlikely materials into this photographic process. Often working in series Vik has used dirt, diamonds, sugar, string, chocolate syrup and garbage to create bold, witty and often deceiving images drawn from the pages of photojournalism and art history. His work has been met with both commercial success and critical acclaim, and has been exhibited worldwide. His solo show at MAM in Rio de Janeiro was second only to Picasso in attendance records; it was here that Vik first exhibited his 'Pictures of Garbage Series' in Brazil.

Fabio Ghivelder

Vik's collaborator and the director of his studio in Rio de Janeiro was crucial to all aspects of the "Garbage" series of works presented in WASTE LAND. Fabio was responsible for identifying JardimGramacho as the site for Vik to make the garbage works. He was in charge of all liaising with the catadores, officials at the sanitation department (Comlurb) and at Jardim Gramacho. He was also the practical mastermind behind creating the new studio in Rio, building the infrastructure required to make these monumental works, ensuring that the artistic environment would meet the standards set by Vik, day-to-day management of the project and liaising with the catadores, overseeing the photo shoot at Jardim Gramacho, and most importantly collaborating as Vik's sounding board and key advisor on all creative aspects of the project.

Previously, Fabio managed the production of Vik's highly successful "Junk" series that was produced in the Rio studio. Before returning to his native Brazil to create and run Vik's operations, Fabio lived and worked in NYC for many years in various professional capacities in the photographic world. Fabio has a wicked sense of humor, is a great raconteur, huge fan of various television series such as "Seinfeld" and forms an amazing comedic double act with Vik!

Catadores

CatadoresTiao (Sebastiocarlosdos Santos)

TiaƵ is the young, charismatic President of ACAMJG (the Association for the Pickers of Jardim Gramacho), a co-operative to improve the lives of his fellow catadores. Inspired by the political texts he found in the waste, Tiao had to convince his coworkers that organizing could make a difference. TiaƵ has been picking since he was 11 years old.

Zumbi (Jose Carlos Da Silva Bala Lopes) is the resident intellectual. When he sees a book, he doesn't see just recycling paper. He has kept every book he's ever found on the landfill, and he has started a community lending library in his shack. He is on the Board of the Association of Pickers of Jardim Gramacho, ACAMJG. He has been working at Jardim Gramacho since he was nine years old.

Suelem (Suelem Pereira Dias) has been working in the garbage since she was seven; now she's 18 with two kids and another on the way. She's proud of her work, because she's not a prostitute or involved in the drug traffic, those being her only other career options. Still, she'd love to be taking care of children, or even be able to stay home with her own children.

Isis (Isis Rodrigues Garros) loves fashion and hates picking garbage. When she falls apart she reveals the tragedy that brought her to the dump.

Irma (Leide Laurentina Da Silva) Irma is the resident chef, cooking up a plat du jour from the freshest ingredients she can find at Jardim Gramacho.

Valter (Valter Dos Santos) is the landfill elder statesmen, recycling guru and resident bard who delights in rhymes and morals.

Magna (Magna De Franca Santos) fell on hard times when her husband lost his job. Her fellow bus passengers may turn their noses up at her, but she tells them at least she's not turning tricks on Copacabana.

MORE