Robert Frank Don't Blink

Robert Frank Don't Blink

Cast: Mena Suvari, Joanne Kelly, Brian Austin Green

Director: Laura Israel

Genre: Horror, Mystery

Running Time: 82 minutes

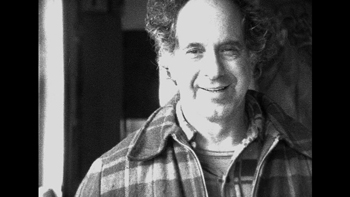

Synopsis: The life and work of Robert Frank"as a photographer and a filmmaker"are so intertwined that they're one in the same, and the vast amount of territory he's covered, from The Americans in 1958 up to the present, is intimately registered in his now formidable body of artistic gestures. From the early '90s on, Frank has been making his films and videos with the brilliant editor Laura Israel, who has helped him to keep things homemade and preserve the illuminating spark of first contact between camera and people/places. Don't Blink is Israel's like-minded portrait of her friend and collaborator, a lively rummage sale of images and sounds and recollected passages and unfathomable losses and friendships that leaves us a fast and fleeting imprint of the life of the Swiss-born man who reinvented himself the American way, and is still standing on ground of his own making at the age of 91.

Don't Blink

Release Date: December 1st, 2016

About The Production

About The Production

Unexpected Beginnings

Director Laura Israel has built up an impressive resume of artistic collaborations throughout her career – Lou Reed, Sonic Youth and John Lurie are among those who've enlisted her talents in the realm of montage. Israel decided to step into the director's chair herself for 2010's Windfall, a critical documentary about the wind turbine industry attempting to establish a foothold in upstate New York. The lauded doc played some of the world's most prestigious film festivals, including Toronto and IDFA.

It was while touring with Windfall that Israel ended up determining the topic of her next directorial effort, which originally seemed an unlikely prospect to her: a portrait of living-legend photographer Robert Frank, the 90-year old master who revolutionized photography with his famous series The Americans before moving into more abstract realms of photography and cinema.

Israel has been working as Frank's editor since the late 80s, and she ended up in a conversation at IDFA about Frank's life. 'I spoke to somebody there who suggested I do a film about Robert," Israel explained. 'I said, -No, no, no. I work with Robert. I don't do films about him.' But on the plane ride home I started to think perhaps it was a good idea."

Israel attributes Frank's change of heart about the project to their longstanding friendship, which engendered a respect and understanding of Frank that made the photographer feel comfortable allowing his life to be depicted by Israel – an allowance he has not made often throughout his life. 'I think it came together because I was very respectful " I never shot any video before asking him, and I think that's a big part of why he eventually warmed up to the doc. That respect and conviviality carried over into the shoot. A lot of times if we were having a long shoot, we would stop and have tea and talk for an hour.

Israel's goal was to provide more than a typical bio-doc portrait, to go deeper than a simple work of mythologizing. 'It was important for me to keep in my mind that I couldn't idolize Robert," she explained, 'Because that's not an honest way to approach something like this. I was always cognizant of that."

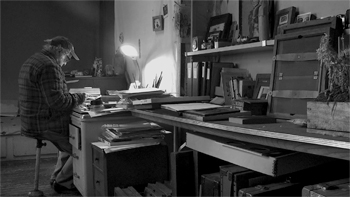

Instead, Israel decided to analyze Frank's creative process – which of course she'd already been given the opportunity to examine through their decades of collaboration. 'I felt like I had the opportunity to provide some insight into his creative process. You sit next to someone for that long and you see the outtakes and the footage, you see what their thought process is, you get a really good perspective on how they make artistic choices. I wanted to share that perspective because I think I've really benefitted from it."

Chief among Frank's artistic attributes that Israel wanted to explore was his style of creation, which owes something to the bursts of energy exemplified by the artists of the Beat Generation with whom he's sometimes grouped (after all, Pull My Daisy was narrated by Jack Kerouac). 'I was interested in sharing my insights into Robert's relentless pursuit of creativity," Israel explained. 'He's big on spontaneous intuition. I think that's something that younger people could use a dose of, and that other people could be inspired by. The creative approach of, -I'm just going to go and do it. I'm going to do whatever comes to my head. I'm going to think about it but I'm not going to think about it too much.'"

With her subject willing and her focus set, Israel commenced the work of putting the documentary together – a deeply personal process in which her crew was never more than a handful of individuals at a time.

The Traveling Structure of Don't Blink

In keeping with the roaming, creatively restless and aggressive nature of Frank's body of work (and uninhibited artistic style), Israel decided to structure Don't Blink as a back-and-forth journey traveling through various aspects of and periods in Frank's life – touching on The Americans, his involvement with the Beats and the Rolling Stones and 60s counter-culture, his experimental film work, as well as his relationships with his wife June Leaf and his children Pablo and Andrea (both of whom died tragically young). The film's structure also includes verite footage of Frank at his home in New York, and on excursions with the filmmakers and with various friends (revered cinematographer Ed Lachman appears late in the film).

For Israel, the decision to not structure the film as a completely linear biodoc was integral to her goal of reflecting Frank's creative process. 'I think it reflects Robert's life to have the film unfold and build upon itself," she explained. 'I think that's the way he works - he looks at his life and he tries to figure out how to have it unfold through his work in a way that is, for the viewer, a bit of a mystery. So I wanted the film to correspond with themes of his life that appear in his work. The film travels from one scene to the next and instead of telling everybody everything right up front, it takes detours back and forth between various subjects – like Robert's own body of work. I think that makes it a bit different for people to experience and as a result I think it forces the viewer to become more involved."

While Frank is known foremost for his work in the realm of photography – especially the manner in which he revolutionized photojournalism with The Americans – Israel devotes a significant amount of time to an exegesis of Frank's cinematic works, including the aforementioned Pull My Daisy, which he completed in 1959, one year after he finished The Americans. Frank's interest in moving back and forth between the mediums of photography and cinema illustrates why Israel was so interested in a traveling, back-and-forth structure. 'I read an interview where someone asked Robert once, -Why did you start making films?' and he said, -It's like walking into another room. I'm walking into that room and then when I walk back into the room I was in, it's more interesting because I've been somewhere else, and I can use that experience.' Detours outside of your normal realm provide some perspective."

Frank's love of the detour in art carries over to the freewheeling, open manner in which he conducts his life – a manner that Israel captures in various interviews in the film. 'Robert really is interested in the idea of, -Oh, let's get lost for a while, and then we'll go back to what we were doing, you know, or go back on the road.' At one point when we were shooting we went on a road trip and I said, -We need a map. You know, we're going to get lost.' And he said, -No, let's just get lost. Forget about the map. Don't bring the map.'"

Frank's love of the detour in art carries over to the freewheeling, open manner in which he conducts his life – a manner that Israel captures in various interviews in the film. 'Robert really is interested in the idea of, -Oh, let's get lost for a while, and then we'll go back to what we were doing, you know, or go back on the road.' At one point when we were shooting we went on a road trip and I said, -We need a map. You know, we're going to get lost.' And he said, -No, let's just get lost. Forget about the map. Don't bring the map.'" Frank's improvisational style forced Israel and her crew to remain on their toes at all times – providing them with a kind of trial-by-fire throughout the shoot that forced them to adopt Frank's off-the-cuff working methods in their own work. 'Robert didn't take direction very kindly!" Israel said with a laugh. 'It's pretty funny because we asked him at one point " he had pulled the shade up and we said, -Oh, we didn't get that. Could you do that again?' And he pulled the shade down instead. It was funny but he did the exact opposite thing of what we wanted, and we started to understand that about him."

Israel's attempts to plan out shoots in advance were subject to similar whims of Frank's creativity. 'At one point, when we had a shooting day traveling around with him, we made this whole plan of where we were going to travel to, and then in the end he just said, -I want to go to Staten Island,' so we wound up trying to get on the Staten Island Ferry, which made us end up in whole different direction. He loves to put a wrench in the plan, whatever plan it is, just to see how you deal with it. It was fun actually, to be prepared for that. It's really nerve wracking but it can be fun if you go with it. So he did that on purpose just to shake us up a little and have things happen more organically."

Israel spends much of the film bringing to light aspects of Frank's life that are lesser-known, as she herself was interested in uncovering new facts about the man she'd been collaborating with for over 20 years. 'I felt like I knew him well enough to make the film so I actually shot a lot of it and then did research after I began shooting. I thought I knew everything about him, but once you start to look at the vast amount of his work out there, you become surprised. I didn't know that he wrote so many articles about photography when he was younger. But once I got to know the photography and his history a bit better, some of the films that I knew by heart made more sense to me. There were things in them I started to understand on a deeper level, catching certain references I hadn't noticed before. I wanted to help people understand him on a deeper level than they get to when they just see his work, without having much context."

Frank's artistic collaborations are widely associated and varied, but Israel was surprised to learn that in the late 60s Frank made documentary collaborations with Stewart Brand and Wavy Gravy, which she ended up excerpting in her film. 'I had no idea he had worked with Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog crew. Once I found out about that, it seemed like such a natural progression, that he would be into the Beats and then he would be into those guys. Then the Living Theater Vietnam war protest footage he shot made more sense to me. I met him in the 80s, so the downtown East Village punk scene was the prevailing subculture I was more familiar with."

Much of the documentary touches on Frank's collaborative nature, which – exemplified by his work in cinema – sets him apart from many other master photographers, who often work in relative isolation. Israel sees that collaborative nature as key to the portrait of Frank she wanted to depict. 'The fact that Robert hung out with poets, painters, actors – it really distinguishes him from so many other photographers and highlights what's unique about him. It's also why he was drawn toward filmmaking – because it's collaborative. He likes life, he likes people, he's inspired by people. In some archive we did not use in the film, Allen Ginsberg actually talked about how the reason why Robert was so attracted to Julius Orlovsky, a catatonic, and made a film about him is he really wanted to see what made Julius tick. His approach wasn't, -Oh, I feel sorry for this guy.' It was more like he felt some sort of connection to Julius as an equal, and felt a common bond with him as an outsider. Robert looks at people. He looks really hard. In a way, the funny thing about Cocksucker Blues is the fact that he was really just looking at The Rolling Stones and just saying, -Okay, this is what these guys do.' I think they wanted something done a little bit differently, obviously."

Israel's film is a comprehensive portrait of the varied stages and works in Frank's career, but Israel also wanted to provide an intimate portrait of Frank's personal life. Frank's wife June Leaf, also an artist, is also featured in the film, and her presence was crucial for Israel. 'With the film, there was something extremely important that I wanted to portray, and that was what it's like to have two very strong people living together and working each on their own, but side by side. Robert and June are both very strong but very individual personalities and they support each other's work. I think that really comes out in the film.

Through explorations of Frank's work, Israel also touches upon perhaps the saddest chapter in Frank's personal life – the loss of both his son and daughter. Israel found that the most effective way to explore those losses was by examining how Frank addressed them in his work. 'I think portraying those losses through how they're presented in his work is more honest and much more lyrical. I think that that is where he really is the most honest about it, in his work. I think the work says a lot more than any direct comment about what happened to his children could – and to me, it's a lot more poignant."

The approach of examining Frank's deeply personal losses through his work exemplifies Israel's larger strategy for the portrait – to continually refer to Frank's work in order to better understand the man. 'Every time I approached a scene I said, -Okay, should this be about his work, what happened in his work? Or should this be about his life?' It's interesting, I tried to vary it a little so that you're kind of on a road, touching these different points. A lot of time it just all came together. It seems like the film sort of made itself because I kept following the work. We would always say, -Let's go back to the work. Let's look at the work. It's somewhere in the work. We'll find it.'"

The approach of examining Frank's deeply personal losses through his work exemplifies Israel's larger strategy for the portrait – to continually refer to Frank's work in order to better understand the man. 'Every time I approached a scene I said, -Okay, should this be about his work, what happened in his work? Or should this be about his life?' It's interesting, I tried to vary it a little so that you're kind of on a road, touching these different points. A lot of time it just all came together. It seems like the film sort of made itself because I kept following the work. We would always say, -Let's go back to the work. Let's look at the work. It's somewhere in the work. We'll find it.'" Examining her own work, now from the remove of having completed her portrait, Israel recognizes that the film has gone through various permutations. 'I've heard that as a director there's always three films. There's the one that you started making, there's the one that you shoot, and then there's the one that you edit and end up with. I think that throughout this process, those three things became different things for us, and for Robert. I think in the beginning he thought, -Oh, we're just making this little film and it's going to be a ten minute video or something.' And then when I started researching and talking to him more, he started to realize it was a much different film than he thought it was going to be."

As the film's scope expanded, Frank became more involved in the production itself, perhaps recognizing the documentary's power to orient new audiences toward and understanding of his body of work. 'Eventually Robert became involved on a bigger level. He would call and say, for example, -My friend made these big contact sheets of The Americans. Do you want to come over and we'll talk about them?' Then when I started to show him longer cuts, I think he enjoyed the humor in the film. I think he enjoyed that about the film, that it had this unexpected quality to it, that's it's not a straight documentary."

Ultimately, Israel sees the film as being a portrait that enables audiences to engage more deeply with Frank's career, post-Americans. 'I would like this film to be a stepping stone for people to understand where he went after The Americans, where he was going after that. You know, before The Americans journalistic photography was more about the captions than the photographs. You couldn't have a photograph that said something striking in the image. His photographs didn't need captions but also rather than trying to explain something they evoked a feeling. So the fact that he revolutionized the notions of photography at that time but then continued to move forward was important to convey in the film. That's why I started with The Americans in the film because I wanted people to use that as a departure for the rest of his work and I think it was very important for enabling him to do what came after, but for me it's just as amazing to look at the Polaroids books he's done more recently, his scratching on negatives, his videos. In the end, the film is about photography and cinema, and how for Robert they're interchangeable – it's just him expressing himself as an artist. And his imagery transcends typical boundaries."

Don't Blink

Release Date: December 1st, 2016

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview