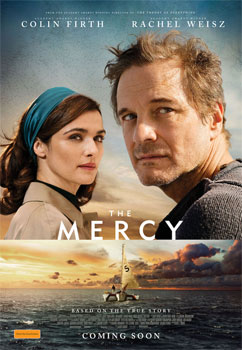

Rachel Weisz The Mercy

"I am going because I would have no peace if I stayed." " Donald Crowhurst

Cast: Colin Firth, David Thewlis, Rachel Weisz

Director: James Marsh

Genre: Drama

Synopsis: Following on from his Academy Award® winning film The Theory of Everything, James Marsh directs the incredible true-story of Donald Crowhurst, an amateur sailor who competed in the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in the hope of becoming the quickest person to single-handedly circumnavigate the globe without stopping. With an unfinished boat and his business and home on the line, Donald leaves his wife, Clare, and their children behind, hesitantly embarking on an adventure on his boat, the Teignmouth Electron.

Not long after his departure, it becomes apparent to Donald that he is drastically unprepared. His initial progress is slow, so Donald begins to fabricate his route. His sudden acceleration doesn't go unnoticed and he soon emerges as a serious contender in the competition. Donald's business partner, Stanley Best, had reminded him that he could pull out at any time, however, the consequences to his family from such a decision are unthinkable; Donald has given himself no other choice but to carry on. During his months at sea, Donald encounters bad weather, faulty equipment, structural damage and, the most difficult obstacle of all, solitude.

One by one, his fellow competitors drop out until it is only Donald left to challenge Robin Knox-Johnston, who is first to complete the round trip. As the pressure from what awaits him back home increases, Donald faces his toughest challenge, maintaining his sanity. When he receives word from his press officer, Rodney Hallworth, of the recognition and celebrations awaiting him upon his return, Donald's mind finally breaks.

The Teignmouth Electron is found abandoned off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Donald's scrawled logs are inside, filled with ramblings of truth, knowledge and cosmic beings. Back home, his wife Clare is left without a husband, his children without a father.

The Mercy

Release Date: March 8th, 2018

About The Production

An Introduction

May 2015 saw the start of principal photography in the UK and Malta on The Mercy, the highly anticipated new feature film based on the true story of amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst and his attempt to win the Sunday Times Golden Globe round the world yacht race in 1968. Helmed by Academy Award®-winning director James Marsh (The Theory of Everything, Man on Wire), Academy Award® and Golden Globe-winner Colin Firth (Kingsman: The Secret Service, The King's Speech, A Single Man) stars as Donald Crowhurst.

Scripted by Scott Z. Burns (The Bourne Ultimatum, Contagion, Side Effects), the stellar support cast includes Academy Award® and Golden Globe Award-winner RACHEL WEISZ (The Constant Gardener, The Bourne Legacy, The Deep Blue Sea) as Donald's wife Clare Crowhurst; David Thewlis (Harry Potter, The Theory of Everything) as his press agent Rodney Hallworth; Ken Stott (The Hobbit) as his sponsor Stanley Best, and Jonathan Bailey (Testament of Youth, Broadchurch) as rookie reporter Wheeler.

Produced by Pete Czernin and Graham Broadbent through Blueprint Pictures and Scott Z. Burns, alongside Nicolas Mauvernay and Jacques Perrin of Galatee, the project was developed with Christine Langan from BBC Films and Studiocanal. Director James Marsh comments: "Donald Crowhurst's story is an extraordinary and haunting tale of a man going to sea and the family he leaves behind. Scott has written a beautiful script that gets to the heart of the myth of Crowhurst in a sympathetic and humane way".

Who Was Donald Crowhurst?

Donald Crowhurst was born near Delhi in British colonial India in 1932 to John and Alice Crowhurst. At the age of eight he was sent to an Indian boarding school where he would spend nine months of the year. Two years later, his parents moved to Western Pakistan. After the Second World War, aged fourteen, Donald was sent back to England to board at Loughborough College. His parents returned to England in 1947 when India gained Independence from Britain and the Partition took place. His father ploughed all of his retirement savings into an illfated business deal in the new territory of Pakistan. The Crowhurst's life in post-war England was a far cry from colonial life. The lack of funds forced Donald to leave Loughborough College at the age of sixteen once he passed his School Certificate, and sadly John Crowhurst died in March 1948.

After starting as an apprentice in electronic engineering at the Royal Aircraft Establishment Technical College in Farnborough, Donald went on to join the RAF in 1953; he learned to fly and was commissioned. He enjoyed the life of a young officer and was described by many as charming, warm, wild, brave and a compulsive risk-taker who defied authority and possessed a madcap sense of humour. After he was asked to leave the RAF, he promptly enlisted in the army, was commissioned and took a course in electronic control equipment. He resigned from the army in 1956 and went on to carry out research work at Reading University aged twenty-four.

Crowhurst is remembered as being quite dashing and he caught the attention of his future wife Clare at a party in Reading in 1957. Clare was from Ireland and had been in England for 3 years. Apparently he told her that she would 'marry an impossible man". He said he would never leave her side and took her out the very next evening. Theirs was a romantic, whirlwind courtship that took place over the spring and summer of 1957. They married on 5th October and their first son, James was born the following year. It was at this time that Crowhurst began sailing seriously.

He secured a job with an electronics firm called Mullards but left after a year and aged twenty-six, he became Chief Design Engineer with another electronics company in Bridgwater, Somerset. His real dream was to invent his own electronic devices and he would spend hours of his spare time tinkering with wires and transistors creating gadgets. He also found solace in sailing his small, blue, 20-foot boat, Pot of Gold.

Crowhurst designed the Navicator, a radio direction-finding device for yachting and set up his company Electron Utilisation to manufacture and market the gadget. Donald and Clare's family expanded with the arrival of Simon in 1960, Roger in 1961 and Rachel in 1962 and they lived happily in the Somerset countryside.

When Electron Utilisation hit financial difficulty, Crowhurst was introduced to Taunton businessman, Stanley Best, who agreed to back the company and Best eventually sponsored Crowhurst's attempt to circumnavigate the world in the trimaran Teignmouth Electron.

With the Empire gone, in 1960s Britain there developed a phenomenon where men sought adventure, recognition and heroism. Sending men to the moon was something Britain couldn't afford, so instead, heroes came in the form of people like Francis Chichester who was the first person to tackle a single-handed circumnavigation of the world, starting and finishing in England with one stop in Sydney. Upon his return in 1967, Chichester was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II and instantly became a national hero.

Capitalising on this wave of interest in individual round the world voyages, The Sunday Times sponsored the Golden Globe race, a non-stop, single-handed round the world yacht race. No qualifications were required for entrants but the rule was that they had to depart between 1st June and 31st October 1968 in order to pass through the Southern Ocean in summer. The trophy would be awarded to the first person to complete the race unassisted via the old clipper route, of the great Capes: Good Hope, Leeuwin and Horn. The newspaper also offered a cash prize of £5000 for the fastest single-handed navigation.

Nine sailors started the race, four retired before leaving the Atlantic Ocean. Chay Blyth who had no previous sailing experience, retired after passing the Cape of Good Hope. Nigel Tetley was leading the race but sank with 1,100 nautical miles to go. Frenchman Bernard Moitessier rejected the commercial nature of the race, so abandoned it but continued sailing, completing the circumnavigation and carried on half way around the globe again.

Donald Crowhurst's Teignmouth Electron was discovered mid-Atlantic, 1,800 miles from England at 7.50am on 10th July 1969 by the Royal Mail vessel, Picardy that was en route from London to the Caribbean. On inspection, the trimaran was deserted and a subsequent US Air Force search for Crowhurst followed to no avail. British sailor Robin Knox-Johnston was the only entrant to complete the race. He was awarded both prizes and subsequently donated his £5000 prize money to Clare Crowhurst and the Crowhurst children.

Director James Marsh carried out painstaking research and delved deep into the heart and soul of what made Donald Crowhurst tick: 'If I can speculate on Crowhurst's background and his experience, he seemed to have a series of failures, if you like, and he escaped the failure by rolling the dice bigger on the next adventure. He was a man of enormous energy and charm and that energy and charm led him into decisions like the ones he made in joining the race, for example. He had enormous self-belief as well, and people around him substantiated that. He managed to fund and build that boat, so there's a danger of overlooking what he achieved in this story as well as what he didn't achieve. He achieved enormous amounts".

'He was a fairly inexperienced sailor but he wasn't as inexperienced as some people think he was. He hadn't sailed the ocean properly, yet he built this very fast trimaran, but the boat wasn't fully tested and finished. He made a pretty good go at sailing round the world - he stayed out in the ocean for the best part of seven months so all in all, he achieved much more than people ever thought he could, he just didn't achieve what his objective was. It was a case of over-reach, it was hubris and that is what caused the tragedy of his demise", concludes Marsh. The research materials available on Crowhurst were 'endless" says James Marsh, 'there are quite a few books out there and great raw materials that he left behind, his logbooks, his diaries and letters he wrote to his wife".

In the course of the research, Marsh also read a lot about psychology and about isolation, 'You can read about what happens to prisoners who are on their own for six months and what that does to their minds. I made a documentary about a chimpanzee and he went mad within three days. There's something about us as animals that are entirely social".

Marsh found Crowhurst's logbooks to be one of the most fascinating elements of research 'because they're the real thing when they're not the real thing, he's disguising the real thing. You can perceive the real story through the disguise". 'I would drive around the country looking at locations listening to Crowhurst's tapes" recalls Marsh, 'He sings on the tapes, mostly sea shanties and he speculates about the state of the world, about politics, about his own life. It's extraordinary really, some of that is a persona but some of it also is the truth. That's the great joy of this kind of film - you get a chance to research and the more you know the more you want to know".

'There are entries in the logbooks and in the tape recordings that he became aware of the cosmic reality of where he was." comments Marsh. 'No-one behaved rationally after a certain point in that race. Moitessier lost his mind a bit too – he went round again! Robin Knox-Johnston was perhaps the exception but his boat was in a very strange state when he came back to the British coastline. All in all, no-one was spared by this journey".

'The sea is like a desert. It's also mercurial, it has moods, it changes, and it threatens you. But, all you're seeing is a horizon and a sky. The sea changes colour, it can be stormy and it has this sort of personality that can destroy you," muses Marsh. 'The isolation is a huge part of what goes wrong in Crowhurst's mind. Your brain chemistry changes when you don't speak to people".

When a real-life character is portrayed on screen, there comes a certain responsibility to the memory of the person and to the feelings of loved ones. James Marsh doesn't think there is any -definitive' version of any true story, 'that's the great virtue of true stories, you can interpret them this way or that way, endlessly". He says The Mercy is 'a version of a story that we think has some truth to it. There's no definitive version apart from the reality of what actually happened. You capture and distil it somehow into a dramatic form or a documentary form. There is a duty to respect that character and to be sympathetic. Colin and I both respect that – we both really liked Crowhurst, we felt we knew enough about him to go on with this story and get to the truth of it. Colin plays him with such sympathy and such careful precise emotional progression, which is totally profound".

'A lot of artists became quite obsessed with Donald Crowhurst" notes Rachel Weisz who plays his wife Clare in The Mercy, 'I actually think this story is a very loving portrait of him and his ambitions. There's a kind of Donald Crowhurst in all of us, we all dream of some kind of glory. I think in the culture we live in now, we're encouraged to reach beyond our lot or our station. Crowhurst could have made it and it would be a very different story. At the time, there was perhaps this notion that he'd cheated and lied, but I don't really feel the story's about that. It's about somebody who is a dreamer and he gets caught up in a kind of white lie. Everybody exaggerates a little bit now and then to suit his or her story but obviously, this is a very extreme version of it, therefore it makes good drama. I think Donald Crowhurst is immensely human and relatable. He's not a strange, ununderstandable being. I think he's very understandable. I think the essence of the film is celebrating him as a kind of romantic hero. I hope his family might feel that too, because that's my feeling about the film" concludes Weisz.

The Other Key Characters

Clare Crowhurst

Donald's Wife

'I think this film is about family", comments Rachel Weisz, who plays Donald Crowhurst's wife, Clare. 'Donald, the head of the family is an amateur sailor, an inventor, a dreamer and a fantasist, so when he sees a competition in the Sunday Times offering £5000 to the first man who circumnavigates the earth singlehandedly, without stopping, he dreams that he could do this. Chichester had sailed around the world recently, stopping once and he was knighted upon his return and became a hero. It's a story about how boys and men become fixated with becoming heroes".

'I think Donald had a lot of madcap ideas which often didn't get carried out, so at first when Clare hears he's going to enter this race, it's such a preposterous idea to her, because he's not a professional sailor, he's just pottered around. I don't think she believed he would actually do it. Slowly but surely it dawns on her that he's getting closer and closer to actually going and there's a moment where she asks him -Are you really going to go?' and he says -yes'".

The question is - could Clare Crowhurst have stopped her husband from embarking on this risky challenge? 'Perhaps he would have been stoppable," says Weisz, 'but from my viewpoint, it's a portrait of a marriage and a relationship and what would have happened had she stopped him from going? Would he ever have forgiven her? In a relationship, can you stop the other from living out their dreams? In this case, it turns out to be tragic decision. Clare Crowhurst has said in interviews that she felt retrospectively that she should have stopped him. But, I think in the moment, she didn't feel like she had the right to. She was in an impossible situation."

'It sort of becomes two films, the one at sea, where myself and the children are not there, and then there's the family home, waiting for news of her husband and their father who is becoming a national hero whilst he's at sea. Clare has to deal with the press, with long periods of silence and Christmas and birthdays without him. She also has to deal with having no money to buy food or heat the house without him because Clare depended on Donald for money."

In the course of her research for the film, Rachel Weisz got a sense of Clare from the documentary Deep Water and from reading about her, 'that she really wasn't interested in being married to someone famous. I sense that she loved him very, very deeply and she didn't want to stop him living out his dreams."

'At that time in history, men were leaving their homes and crossing new frontiers, be it in outer space or circumnavigating the world. So, for Clare, she was happy he was going to be successful as that was going to make him happy" muses Weisz, 'I think she was happy if Don was happy."

When an actor approaches a role where the character being portrayed is real and still alive, there comes a certain responsibility. Rachel Weisz was keen not to do an impersonation of Clare Crowhurst, but to simply convey something of her spirit as she explains, 'I think it would be different if one were playing someone already iconic, as everybody would know what they looked like and how they spoke. I'm playing a real person who has been very media-shy. She has not sought fame or publicity, she was never interested in that. I want to honour her. I watched a lot of footage to get an essence of her but at the end of the day, it's me being her".

In telling Donald Crowhurst's story on the big screen, Rachel Weisz hopes, 'We're celebrating the beauty of being a dreamer, the beauty of thinking big, wanting great things and following one's passion and one's heart towards doing something incredible."

'Rachel is one of those actors who just surprises you and does things you don't quite expect her to", recalls Marsh, 'that flushes out things in other actors. I loved working with her. She really relies on instinct, she doesn't really like to do lots of rehearsals or commit to things. Rachel always wants to be loose and to respond. I love that style of work from her."

Screenwriter Scott Z. Burns feels that for the audience, the voyage Clare goes on is just as important as the voyage Don goes on, 'You get the sense that her insight into her husband – both in terms of his need to go and her acceptance of what happened afterwards – is extraordinary, it's from a place of reluctance to a place of forgiveness."

'The great thing about Rachel is that she understands the strength of Clare Crowhurst", observes Burns. 'Rachel also understands that the moment in history we're talking about, also asked certain things of a woman in terms of being a wife. I think she very quickly understood the journey Clare went on. On one had she wanted to be loving and nurturing but you also see a very progressive thinker. Most people would be aghast at the prospect of their husband setting off on this kind of adventure, but Clare understood how fundamental it was to his being and that casts a really interesting light on their relationship."

'To me it's a love story", concludes Rachel Weisz, 'you don't see them meeting as teenagers, you meet them when they have children and they're settled into their marriage. I think they were passionately in love with each other and Clare's whole life is Donald. She didn't have a job, though I think she wanted to teach amongst other things, and to write. But she was a mum and very devoted to Donald. That's how I perceive her. I guess what makes it so romantic is the fact that they're separated because that's what old school romantic with a capital -R' means – something that's unattainable, unfulfilled and broken. That's why it's tragic because I think they were yearning for each other while they were separated."

Rodney Hallworth

The Press Agent

'I remember my parents being quite taken with the story of Sir Francis Chichester in the 1960s when I was a kid, but I didn't know the Crowhurst story" recalls actor David Thewlis who plays Crowhurst's press agent, Rodney Hallworth.

When Thewlis received the script for The Mercy from his agent, he was 'absolutely fascinated straight away. It was one of the rare occasions where I read it in the morning and rang James Marsh immediately afterwards and said yes. There was no doubt and having worked with James before on The Theory of Everything, I knew he was good news I've had a great time immersing myself in the history of this story. There's lots to research about it and it becomes a little obsessional".

Thewlis devoured the 'embarrassment of riches" in the documentary footage, Crowhurst's recordings and the BBC interviews of the time with Rodney Hallworth, 'Everyone involved gave extensive interviews so we've all had access to that" shares Thewlis. 'We've read all the books and seen all the documentaries and during the shoot in Teignmouth, we met people who remember the actual events. Some of the extras were friends of my character Hallworth and I even had a letter from a gentleman who was more or less the character of Wheeler. It's incredible to have so much information available and the story's really just a compression of all that. There's no exaggeration – there doesn't need to be, it's such an extraordinary tale."

Rodney Hallworth was a larger than life character, a former crime reporter for the Daily Mail, he ended up living in Teignmouth running a local news agency and acting as PR for Teignmouth Council. He offered himself up as Donald Crowhurst's press agent, 'The story takes quite a dark twist with Hallworth" explains Thewlis. 'With the role he plays in embellishing what's going on. He's not complicit with what Crowhurst is doing, he actually believes he's going round the world but, he's not receiving enough information from Crowhurst so he starts to get a little creative and exaggerates the speeds and the whereabouts of Crowhurst on the map. This doesn't help the world understand the real story, it doesn't help Crowhurst's family and it doesn't help Crowhurst because Hallworth is reporting it as a certainty that Crowhurst has rounded the tip of Africa. Crowhurst hadn't and therefore this made it increasingly difficult for him to give up and turn back. I think Hallworth was the man who pushed Crowhurst when the boat wasn't ready to go and he was the man who said -You've got to go, there's too much to lose'".

Thewlis feels 'if there's a villain of the piece, it's Hallworth, but it's not as simple as that because he's also an innocent to a degree in that he doesn't know what's really happening."

Crowhurst cites Hallworth many times in his log as being the main person he would be letting down, as well as Stanley Best who was his sponsor. He feels that his wife Clare would be more understanding but Hallworth wouldn't.

Portraying Rodney Hallworth allowed David Thewlis to tap into 'a kind of Shakespearean clownish element". Hallworth also exhibited dubious, Machiavellian traits, not least when he went aboard the Teignmouth Electron in the Dominican Republic, 'He entered the cabin and found the logs and discovered the truth. He discovered the rambling, the diaries and the insanity and a very high likelihood of suicide so he ripped out the final two pages of the log, then negotiated the sale of the logs to the Times newspaper, without Clare Crowhurst's permission" explains Thewlis. 'Whoever he was, that was not cool. We can forgive him for some of his part in the story, but not for what he did at the end."

The real Rodney Hallworth died in 1985 but Thewlis still felt a responsibility to the character as he explains 'We were on the beach filming with some extras who were all men in their 70s who were all very happy to let me know that they knew Rodney and they used to have a drink with him, which kind of freaked me out a little bit and I did suddenly feel very responsible."

Director James Marsh views Hallworth as 'an old fashioned Fleet Street hack. He's always got a pint on the go and is often slightly intoxicated". With a background in crime reporting, Marsh notes that he must have" dealt with the really grubby tabloid stuff of the era and he brings some of that mentality to press representation. He's a very cynical man and an opportunist and David Thewlis caught all of those things so beautifully."

Marsh doesn't feel that Hallworth is completely the villain of the piece, 'Everyone has their reasons for doing what they do and to be fair to Rodney, he exaggerates Don's story as it's being conveyed to him from the boat. He embellishes it and adds to the lie. He feels cheated and as a tabloid crime reporter, he feels he's been had. So, his anger and indignation are personal but also professional. I can see where he was coming from at the end. He had pathos for Don in his own cynical way, he felt responsible, as did Stanley Best but they didn't know what they were getting into."

'Rodney is the voice of the future", observes screenwriter Scott Z. Burns, 'he's sort of an entry point into reality TV and what we live in now. He was a man of his time and he'd made a promise to the people of Teignmouth, he'd made promises to sponsors, he'd taken up a lot of his own time and invested in this. At one point, he said that it was his job to make Don the most famous man in England and he did that. The way he did it was brutal and insensitive but I can imagine him being in a position where he'd made a commitment to someone who had lied to him so he acted in his own best interest. I don't think Rodney was an evil man by nature, I think he was a practical man who had invested in something and he wanted to make good on his investment."

Stanley Best

The Sponsor

Stanley Best was a shrewd, successful businessman who'd made his money as a caravan dealer in the coastal town of Teignmouth, Devon.

Ken Scott portrays Best in The Mercy and weighs him up as 'A very ordinary man of no distinction who grabbed the opportunity to be part of something quite splendid. The relationship with Donald Crowhurst was friendly. Stanley Best liked him very much. It seems that Crowhurst was the kind of man anybody could like because he was charismatic."

Stott says that it's worth noting 'Stanley Best didn't do anything just for the hell of it. He wasn't a big risk taker. He liked things to be neatly sewn up. That contributed greatly to what could be considered a modern Greek tragedy in its immensity". 'It would have been acceptable for Crowhurst to come home but the pressure was on him and Stanley Best put that pressure on him, somewhat unwittingly I'm sure. I do believe Best blamed himself in many ways but the family reassured him, that they didn't hold him in any way responsible."

'What makes this story so touching is Crowhurst's love of his family", observes Stott, 'and it's that love for his family that put him into such jeopardy. The irony is the tragedy. It is a painfully beautiful story."

From Script To Screen

Scott Z. Burns' original vision to James Marsh's realisation Acclaimed director James Marsh comes from a documentary filmmaking background and was responsible for Man on Wire, winner of the 2008 Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards®. His multi award-winning feature, The Theory of Everything explored the early life of physicist Stephen Hawking, so Marsh is no stranger to real life characters being portrayed on film and it is indeed something he responds to 'because it offers the opportunity to carry out detailed research, which deepens your understanding of the story".

'Crowhurst's is a real story, a true story, but it's definitely a mythical story of the sea and it sort of seeped into the culture as an example of British amateur sailor overreaching" comments Marsh. 'The idea of -hubris-nemesis' is built into the story. I saw the documentary Deep Water about ten years ago and it fleshes out the imprint you have. It's an absolutely fascinating and compelling narrative. It's literally classical Greek tragedy. A man has an ambition and ambition doesn't end up ennobling him, it ends up corrupting him, and tragedy then ensues. It has a very classic tragic shape."

Marsh received the screenplay from acclaimed American screenwriter Scott Z. Burns, 'He's a great writer and being American, his perspective was very interesting. He took this very archetypal English story and was very detached from his point of view, so was able to cut through some of the baggage of the story and distil it into something really, really strong and compelling to read. It had a very interesting perspective on the unravelling of a human mind, which is again, part of this story. I was won over by the script and really wanted to do the film", recalls Marsh.

'For me, it's always a positive if the story is true" admits Marsh, 'it just gives you a sure foundation if people made these choices and you've to understand their story in a dramatic context. They're real choices and you have to reckon with those and there's something more persuasive about that than some fictional stories. There are always turning points that you look for in a true story as it gives you a larger insight into the human psychology and you can be constantly surprised by the choices people make. In our era, a true story seems to be one that people increasingly respond to. It's a very interesting time for a filmmaker like me who has a background in documentary and also wants to make dramatic film, as the barriers are just breaking down".

'I'd never really understood the term, -Truth is stranger than fiction' until I saw the documentary Deep Water" admits producer Pete Czernin. 'We were incredibly lucky to have such an amazing and very clever screenwriter in Scott who knew about and had pursued the story over the years. You have to decide what sort of story you're going to tell, especially in this instance where what Crowhurst did was so incredible and brave, flawed and interesting, so you need to strike the right balance. A lot of work went into this screenplay to get the tone right. James Marsh also had a sort of forensic intelligence and was exactly the right director for us because of his documentary background. He also has a real passion for telling real life stories. The Theory of Everything was so truthful, interesting and unusual, we were genuinely excited when James became interested in The Mercy. As I hoped he would, he immersed himself in all the source material and became really passionate. It was an absolute blessing that James came on board."

'A lot has been written about Donald Crowhurst and I wanted to get as close as we possibly could to telling the authentic story", explains Czernin. 'Some people have been of the opinion that he cheated and he did this or that wrong but I disagree, I think he was immensely heroic. He found himself in a peculiarly difficult situation and he explored a way to get out of it. I don't think he in any way set out to do what he did. He was heroic and brave. Having the notion in the first place, entering the race, designing the boat, building the boat, raising the money – that's a pretty impressive guy. I love the idea of a man trying to do something that may or may not be beyond his reach. That makes for a very human, fantastic story." Colin Firth had already expressed interest in portraying Donald Crowhurst before James Marsh boarded the project. 'I thought it was just too good to be true, I was thrilled", recalls Marsh. 'As an actor, Colin invites sympathy and I thought he would be the perfect person to take us on this very dark journey. The story starts very optimistically and ends in a state of madness. It's a real challenge for an actor to plot and understand that journey and to do it so utterly persuasively and convincingly. When I realised Colin was involved, it just made me more excited about the project. He has huge talent and experience but he also had personal engagement with the story and a commitment to it that was all consuming. There was technical preparation and psychological preparation and what he had to do was extraordinarily difficult. It's a sort of psychological version of what Eddie Redmayne did in my last film, The Theory of Everything. Colin was able to bring out the pathos in a man losing his mind. The reasons why Crowhurst unravels are very forgivable – isolation, lack of communication with his loved ones, the pressure of what he was doing, the deception and the guilt. Colin and I both saw a lot of ourselves in Crowhurst, for good and for bad. There was a mutual interest and solidarity with the character. It was a very rewarding and harmonious collaboration."

James Marsh and Colin Firth were both in agreement about the story they were telling and they had a shared passion and desire to bring Crowhurst's story to the big screen. 'We're telling the story of a man who, in a sense, wants to have the recognition that he doesn't have in life. He strives for that by doing something very brave and very foolhardy" comments Marsh. 'That venture and objective destroys him".

Screenwriter Scott Z. Burns first became aware of the Crowhurst story through the documentary Deep Water, 'I saw it at a very small theatre in LA and it was one of those stories I identified with in a lot of ways and I knew I had to tell this one. There were a lot of books around and because of the nature of Don's voyage and the support of the BBC, there was newsreel footage, logs and tape".

Burns was aware of the conflicting stories and the differing conclusions people came to about Donald Crowhurst, his motivations and his demise. He explains his own motivations, 'I wanted to write about the fact that all of us find ourselves in situations where we've compromised ourselves inadvertently, sometimes even by virtue of having the best intentions and I wanted to try to show some compassion for that. I wanted to write Don as a character that was sympathetic because at the end of the story, I feel that way towards him in spite of what he does."

There was never any suggestion of a Hollywood ending for The Mercy, Burns 'Wanted to show a man who makes a bunch of choices and ends up paying the price. I hope people can identify with the situation Don gets himself in then maybe we'll have more compassion for each other. I hope the way Clare Crowhurst is portrayed in the movie is instructive in some ways, so we can approach each other and the people we love with a little more generosity and a little less expectation. I took from Clare, the notion that when you love somebody, you don't just get to love the good parts, you have to accept the fact that there are bad parts. I think that's what she tried to convey to her children."

During the writing process, Burns reflected extensively on ways that Crowhurst could have solved his dilemma, but he says, 'What's important to remember is that Don didn't have the luxury of what you, or I or the audience can do, which is talk to another person. You can get caught in your own head and feel as though these are your only solutions. Events conspired against him. The fact that a coastguard officer in Argentina chose not to make the phone call exposing Don is extraordinary. When you spend years writing the script, you begin to wonder why he didn't capsize his boat and radio for help. Yet, if you read Moitessier's book, you learn that sailors love their boats and that relationship they have after nine months at sea, is not one they'd willingly give up."

The Look And Feel

James Marsh returned to Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now as points of reference from literature for The Mercy, 'Herzog's Aguirre, Wrath of God felt like an interesting film to watch because it's about people going mad on a boat and Polanski's Knife in the Water is also an interesting film about the psychology of space on a boat. You look for clues how other great filmmakers have shot in that kind of space. Coppola's way of shooting was very different from Polanski's. Heart of Darkness is a key text for this film or any film about going to sea and civilisation falling away from people and what they become without other people around."

The palette for the film was visualised quite quickly as production designer Jon Henson recalls, 'We used lots of organic blues and colours of the sea. That might sound kind of obvious but using that as a background colour, we dropped in lots of strong colours. Eric our cinematographer found these amazing Capa colour photographs – they're quite unusual and had a real quality to them and that really led the look of the film, as well as the grade. That seeded many thoughts and we laid colours from those palettes into the house as well as the boat."

Keen not to slip into a clichéd 1960s look, Henson wanted to create a naturalistic, simple world that the audience could believe in, 'That's probably been our hardest challenge funnily enough", admits Henson. 'With the Crowhurst's family house, we started to look at wallpapers, colours and 1960s references and they're not all psychedelic bright colours. The Crowhursts were unpretentious, unselfconscious people living a simple life so that's what we've tried to create. My memories of being a child at that time also helped, just small things really that I tried to layer into the film."

One key consideration for Henson was James Marsh and Eric Gautier's desire to create 360 degree sets, even on the boat, 'So that gives it an almost documentary style. We dressed the house completely and the garden so we could feel free to move around in it for two whole weeks. Being able to shoot throughout the house and travel through it brought a particular energy to it."

Constructing The Trimaran Teignmouth Electron

Jim Dines, an accomplished British boat builder, is one of the few people in the UK specialising in boat design and build for the film industry. He and his team created the replica Teignmouth Electron. After accessing the original drawings from a museum in the United States, and as many photographic references he could muster, Dines came up with a drawing and boat design: 'We specialise in building boats that can be dismantled, transported and put back together and still work as a boat rather than being part of a set build."

Dines was given the challenge of building the boat in twelve weeks, on a budget and it had to be transportable by road. The replica Teignmouth Electron is fully functional and was built to sail, although 'It's got limitations" says Dines, 'because it unbolts down the middle of each hull and divides into three pieces. You can take the two outside hulls off the centre hull and get it on a lorry. It had to be under seven feet and six inches in order to transport it by road to Malta."

Constructed in Dines' boat yard in Maldon, Essex, 'We then took it apart, moved it outside the shed and put it back together again so the filmmakers could see it all finished off with the mast and the sails on. We then we took it apart, loaded it onto a lorry and took it down to Portland in Dorset and rebuilt it again, launched it and towed it about 90 miles across Lyme Bay to film in Teignmouth. Then we towed it back to Portland, filmed in Portland, took it apart and put it on two lowloaders and shipped it down to Genoa in Italy, then it went on a three-day ferry ride from Genoa to Malta. We put it back together in a dock in the north of the island, filmed for a couple of weeks, took it apart again and stored it in Malta for a month before returning in September 2015 to put it back together for the fourth time to complete filming in the tank in Malta."

The boat used in the film is as faithful as it possibly can be to Crowhurst's original Teignmouth Electron. Cox's Marine Ltd of Brightlingsea, Essex, built the three hulls of Crowhurst's trimaran then L.J. Eastwood Ltd of Brundall in Norfolk assembled the hulls and completed the fit-out on the boat. Time was of the essence as Crowhurst had a 31st October deadline to set sail, so it was for this reason that the construction was split between the two boat builders as Cox were unable to complete everything in time, hence they sub-contracted to Eastwoods.

The actual name Teignmouth Electron was coined because of Rodney Hallworth's role as public relations officer for Teignmouth, as well as being Crowhurst's press agent. The Electron part of the name is from Electron Utilization, Crowhurst's company.

Jim Dines constructed the hull of the film replica to the same size and specification but used plywood for the frame 'Because we cut it out in the CNC machine just to speed the process up. We eventually got some of the original drawings so we know our sizes were right, apart from stretching the cockpit a little bit to accommodate filming" explains Dines. 'The seats are slightly smaller than they would be but the actual space underneath is slightly bigger so you can get in and out and that meant I could lie down in the floor of the cockpit while Colin was sailing the boat and I could just steer with my finger, looking up the mast and see where the wind vane was. When we were actually sailing at sea, rather than being in the tank, we could drive the boat and hide in the bottom of the cockpit so you're out of shot. The original cockpit would have been too small to do that, so there were a couple of little tweaks we've made to make it work for filming."

Crowhurst wanted to base his trimaran on those of American trimaran pioneer, Arthur Piver, 'He was designing all sorts of different trimaran hulls at that time" notes Jim Dines, 'then there was another guy at the time called Warren who was doing very similar catamaran hulls which were all easy to build – the kind you can do in your back garden as long as you can get it out of the gate. If Crowhurst had finished some of the stuff he was working on, it could have been pretty innovative, like his self-righting systems that he never actually quite got to work. There was a lot of technology he was trying to put on the boat and I think if he'd had more preparation time and money, he could have been in a better state, mentally and structurally before he left."

'A trimaran wouldn't have been my choice if I was doing it, I'd choose something, larger, a steel hull, probably mono-hull. But yeah, trimarans are fast, that's the thing Crowhurst was looking at" notes Dines. 'We've sailed that boat ten or twelve knots and it does fly for a boat with a very small rig in it. Whereas a monohull you're probably looking at seven, eight knots, so you'd think at the time, if you can get the thing round the world safely without it flipping over or falling apart, it would have been fast. Nigel Tetley had exactly the same hull form as Crowhurst, with a slightly bigger rig. Tetley would have done it in a much better time than Knox-Johnston but in the last couple of weeks he pushed the boat so hard that the boat broke and his boat wasn't built for that trip. Crowhurst on the other hand, strengthened up his hulls, took the big cabin off the top and changed the way the boat joins up with the crossbeams, he increased the size of those and things like that, whereas Tetley just had a standard off the shelf boat."

'I think the Teignmouth Electron was capable, so if Crowhurst had been better prepared he would have done it and it would have worked. He just didn't have everything on board that he needed, stuff was taken off that he thought was on board. The boat was very well built apart from the problems with the glass fibre which they put on with the wrong paint because they couldn't get hold of it, and this was something Crowhurst had been dwelling on. In his head, right from the beginning, he was never as prepared as he should have been."

'I hope the film portrays a man who tried to achieve something and do the right thing. I don't think he went out foolhardy, he was just put up against it on time. Back in those days, people went off and did these things. It was a sort of boys' own adventure thing. Chichester did it the year before, only stopping once, so the idea of doing it and not stopping at all was an adventure" concludes Dines.

About The Production

Teignmouth is an early 19th century seaside resort in Devon, England and became one of the most significant locations for filming The Mercy, as it was where Donald Crowhurst set sail from at 4.52pm on 31st October, 1968.

Much of the older generation of Teignmouth vividly recall the day Crowhurst departed on his fateful journey. It was a big event in a small town. Lots of people remembered Crowhurst being around the town, preparing his boat in the weeks leading up to the trip. Half the town showed up to help the unit with the production and to feature as extras in the departure. 'We felt very welcome in Teignmouth, people were happy to have us there" notes director James Marsh. 'We closed down a lot of roads and owned the beach for two days but there was never a problem. There was a general sense of local support because it was a folk memory imprinted into the town. It was great to shoot exactly where Crowhurst had walked. There's archive material showing it hasn't changed very much either which was helpful to us."

'I've not met anyone in Teignmouth who condemned Crowhurst or judged him harshly" notes Marsh, 'because he paid the price, as did his family. His demise was so pitiful and full of pathos, it would be hard to judge him and condemn him on the back of that."

The biggest challenge for location manager Camilla Stephenson was working out the logistics for one of the key elements – filming a man on a boat, as she explains 'We were under the mastership of Daren Bailey our marine co-ordinator, but the second big consideration was that that it's a period film - late 1960s. We needed to be outdoors as much as possible on land as well as being out on the water." One of the first conversations Stephenson had with director James Marsh was about where they would shoot the Teignmouth scenes, 'I looked at Teignmouth and all over Devon but it was evident from the start that Teignmouth itself worked as a location as we could reveal a lot of it. Often with period films you're caught in little corners of a location because behind you or to the side of you is completely wrong period-wise."

The story evokes the image of a small town and it was important to portray that feeling of the people and community who have invested in Donald Crowhurst, 'Visually it's small enough so that you realise the sort of pressure he'd have been under if he pulled out. He couldn't come back and face them all. He'd have felt too humiliated. I don't think Donald Crowhurst sought fame, he sought respect from the community and his own family" comments Stephenson.

'There's something universal in the idea that a small town or community can pin its hopes on somebody. That person becomes the mascot of the people and the keeper of their dreams" suggests screenwriter Scott Z. Burns. 'When you're writing, you're trying to find the specifics so that took a lot of digging and a lot of research and understanding Rodney Hallworth's relationship with Teignmouth. Previously he tried to sell the idea that Teignmouth was the sunniest place in England. The people were looking for an identity, just as Don was looking for an identity." Camilla Stephenson and her team started setting up logistics in Teignmouth from January 2015, with filming commencing in May so they really got a taste of the place and met many individuals who had personal recollections of the Crowhurst story and the historic departure in 1968, 'I got us into the yacht club quite early on and by chance a group of older men were having coffee and they all had an opinion on Crowhurst because they'd either met or heard of him. The story really divides people, some are very sympathetic and others regard him as a cheat. Modern day Teignmouth is very positive and they're proud to have a film about him being made in the town. When we filmed Crowhurst's departure with the mayor officiating on the beach, the man who played the mayor is the son of the actual mayor from 1968."

The importance of the Crowhurst's family home was another major consideration when it came to location scouting. James Marsh and production designer Jon Henson knew that it needed to feel like a real family home and that the audience should get a strong sense of a tight-knit, loving family who all enjoyed being together in their home, 'We wanted to show that they didn't spend their money on a trendy, high-end life, but that they were very much a middle-class family, who really cared about each other. We wanted the home to show a lot about Donald Crowhurst as a person, a husband and a father, as well as showing you a lot about Clare his wife and his children, and that makes it all the more poignant" notes Camilla Stephenson.

On a practical level, Stephenson needed to find a house big enough for the unit to film in for two weeks, 'We initially thought the interior of the house would have to be a set build in a studio but on our first visit to Devon with James and our cinematographer Eric, it became evident that they really wanted to be able to look out of the windows for real". The house she finally found was actually close to Leatherhead in Surrey and it was here that the intimate scenes between Donald and Clare Crowhurst were shot, as well as depictions of family life, Donald tinkering, inventing and plotting in his garden workshop, and winter snow scenes with the Crowhurst children that included snow effects filmed on one of the hottest summer days of 2015.

The logistics of shooting out at sea both in the UK and Malta were a constant challenge. During the UK shoot, aside from shooting Crowhurst's departure from Teignmouth, production moved to Portland in Dorset where the unit battled weather, tides and long hours out at sea.

Producer Pete Czernin admits that every other producer he spoke to said, 'Don't go near the sea". Malta posed its own challenges because of the heat and length of the shooting day out at sea and 'endless problems with the horizon and seeing the land, with other boats passing so you've got to make sure you're far enough out at sea". 'On top of that we were shooting on film so magazines would run out while we were out there so we had all the logistics associated with that but I think Portland and Weymouth was the biggest challenge because of the wind, changing weather and waves. Then there's the fact that the crew need to eat and go to the loo. It was kind of bonkers and very difficult. I don't think I'll make another film on the water in a hurry" confirms Czernin.

In Malta, numbers were limited to eight people on the crew catamaran, when normally you would have around 30 shooting crew. The camera department were on a separate boat, as were hair and make-up there was a main boat for director James Marsh, a safety boat, three or four ribs, then a runner boat. When you're shooting an eight or ten-hour day, three or four miles offshore everything the crew requires has to be on hand, hence the need for the -mothership' as it became known. This large motorboat had amongst other things, essentials like toilet facilities and drinking water. 'You can see why a lot of people don't want to film at sea" says Jim Dines, 'but you do get such a better image, the movement and the whole thing feels much more real".

When asked what his thoughts were on filming at sea again, director James Marsh responded quite simply by saying, 'Well, just not to do it again because it's a foolhardy thing to do in a way. I can see why people want to shoot films in the controlled environment of a tank where you can very easily control the movement of the boat. But, the actual motion of the boat and the experience of shooting with Colin on the boat was so important to the texture of the film."

Marsh worked with French cinematographer Eric Gautier who was also insistent on shooting it for real on the ocean. 'The experience is more like a documentary because it's a minimal unit and Colin. It made the collaboration with Colin so interesting because there were no other actors involved. It wasn't easy. You're stuck out there so you get a small sense of what Crowhurst went through, but it's an amateur's vicarious thrill compared to what he was doing", concludes Marsh.

The Mercy

Release Date: March 8th, 2018

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview