Prince of Persia the Sands of Time Interview Part 2

Surviving Summer in Morocco: On location with triple-digit temps

"Everybody said to us, 'Morocco's a great place,'" recalls director Mike Newell. "'Just don't go there in July and August.' So of course, we shot all the way through July and August."

"I couldn't understand why my hotel was empty when I got to Morocco," says Alfred Molina. "I kept thinking, isn't everybody in Europe on holiday in August? And the local people were looking at me as if to say, What are you doing here? And then I quickly discovered that you don't go to Morocco, 'cause it's too bloody hot! Nobody works in Morocco in August. So, yeah, mad dogs and Englishmen, I guess."

"It makes perfect sense to film a movie about the ancient world in Morocco," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, "because the ancient and the modern coexist side by side. Even with chic restaurants, elegant clubs and boutique hotels springing up all over Marrakesh, artisans in the medina are still hand-tooling their products just as they have for thousands of years. And outside of the cities, life is even more traditional amidst Morocco's mountains and valleys, plains and deserts. With so many films having been made there, there's a great infrastructure with skilled technicians and workers, and the Moroccan government is always very welcoming. Moroccans are great craftsmen, and we used an enormous number of artisans. They did an amazing job."

Cast and crew braved temperatures in excess of 120 degrees Fahrenheit, high altitudes, countless lamb burgers and lethal critters in harsh desert landscapes. Following six months of active preparation, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time began principal photography on July 23, 2008, in suitably epic fashion, with the first two weeks of filming occurring at an altitude of 8,200 feet in Oukaimden, 75 kilometers above the sizzling hot city of Marrakesh. To access this remote location in the High Atlas range, one had to ride through the verdant Ourika Valley and then ascend a winding, rustic mountain road with perilous drops and switchbacks. But it was a perfect site for the film's Hidden Valley location.

It took 20 Moroccan laborers three and a half weeks to build a road into the secluded location. Meanwhile, the first of many base camps that included a massive catering tent and cooking facilities was created, plus all of the production vehicles-from the actors' trailers to tech trucks. An armada of four-wheel-drive Land Rovers was brought in by Morocco transportation coordinator Gerry Gore to ferry the company from the base camp at the foot of the ski lift to the Hidden Valley site-a ride bumpy enough to compete with the Indiana Jones attraction at Disneyland.

Temperatures in midsummer in North Africa rarely drop below 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and during shooting, the average loomed at about 110-115 degrees. During many days of the shoot, the Moroccan locations were either the hottest places on Earth, or something very close to it.

Approximately 18 miles north of Izergane is a flat, dusty, windless stretch of desert called Agafay, where nearly 500 background players portrayed a large chunk of the Persian army as it approaches Alamut. The film's technical and security adviser Harry Humphries and his Moroccan associate Lotfi Saalaoui (a police officer assigned to work with the film's security team) trained the hundreds of local extras. Humphries, a former Navy SEAL and longtime Jerry Bruckheimer associate is one of the motion-picture industry's most experienced technical, military and security advisers. "We had to turn 400 people into a marching army within a very short period of time," says Harry Humphries. "Luckily, Sergeant Lotfi is an excellent drill sergeant, so although none of the extras had ever seen a drill field before, he turned them into an excellent marching force in just three days."

Approximately 18 miles north of Izergane is a flat, dusty, windless stretch of desert called Agafay, where nearly 500 background players portrayed a large chunk of the Persian army as it approaches Alamut. The film's technical and security adviser Harry Humphries and his Moroccan associate Lotfi Saalaoui (a police officer assigned to work with the film's security team) trained the hundreds of local extras. Humphries, a former Navy SEAL and longtime Jerry Bruckheimer associate is one of the motion-picture industry's most experienced technical, military and security advisers. "We had to turn 400 people into a marching army within a very short period of time," says Harry Humphries. "Luckily, Sergeant Lotfi is an excellent drill sergeant, so although none of the extras had ever seen a drill field before, he turned them into an excellent marching force in just three days."

Twenty kilometers southwest of Marrakesh, Tamesloht is a dusty, unpaved village consisting of a few shops, some humble dwellings, a gendarme station, friendly townspeople and walls of an ancient kasbah reputed to be 700 years old. It was chosen as the site for the film's fictitious city of Alamut, as designed by Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time production designer Wolf Kroeger. The imaginary locale features a magnificent square with a Taj Mahal-like palace rising 50 feet above the ground, an adjacent red-andwhite structure festooned with balconies, and a central fountain spouting water-all flanked by elephant statues. Streets abound with architectural and decorative detail: scroll shops in a narrow alley bedecked by small, tinkling bells, a pale yellow temple adorned with garlands of vividly colored flowers, arches carved with floral designs in bas relief, plus stalls selling shoes, dried herbs and flowers, and ancient mud walls festooned with imaginative frescoes of men and beasts. "There aren't many sets," says screenwriter Carlo Bernard, "that are so big that you can actually get lost in them!"

"Wolf Kroeger is a real artist," says Jerry Bruckheimer. "He has great vision, amazing attention to detail, and isn't afraid to think big and build big."

Mike Newell agrees: "Wolf Kroeger has a wonderful ability to tune himself. He's fantastic with two things: one is the big overall concept, and the other is expressing the concept through minute detail. He has a painterly eye, and, like myself, he was inspired by Orientalist art. But Wolf Kroeger also did an enormous amount of research into ancient Persian and Near Eastern architecture. We spent days and days looking at pictures of Iran."

Wolf Kroeger's creations for Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time weren't just sets, but complete environments that enveloped the cast and created an alternate world that combined history and fantasy with truly unleashed imagination. Working alongside Wolf Kroeger were supervising art director Jonathan McKinstry (for Morocco), supervising art director Gary Freeman (U.K.), set decorator Elli Griff, prop master David Balfour, armorer Richard Hooper, construction managers John Maher (Morocco) and Brian Neighbour (U.K.), and an entire army of artists and technicians.

The version of pre-Islamic, sixth-century Persia created by Wolf Kroeger and his cohorts comes from a deliberate attempt to interweave authentic architecture and meticulously researched design elements with a high degree of fantasy, as dictated by the fanciful and supernatural element in the story. Alamut is entirely fictitious, a kind of Shangri-la, with a noticeable Indian influence. "From a design point of view," says Jonathan McKinstry, "the sets, set dressing and props are historical-looking pieces. However, because we're not making a factual historical film, we haven't locked ourselves into any one particular style.

And since we are relying on a lot of Moroccan locations, there's admittedly some North African flavor in the designs as well."

Every design department would rely heavily on the extraordinary skills of Moroccan artisans, craftsmen and builders. Nearly every single piece required by Griff's setdecorating team, David Balfour's prop department and Hooper's armory crew was made in massive workshops in the Marrakesh industrial zone. Items like King Sharaman's ornate horse-drawn hearse and the overweight Mughal's palanquin were created and constructed by Stuart Rose. "Visiting the set-decoration and props warehouses was one of the most amazing experiences I've had on any location of any of our movies," says executive producer Chad Oman. "They were gigantic warehouses filled floor to ceiling with props and production-design elements, from lamps to swords to saddles to all sorts of elaborate weaponry-all of it made right there on the spot, by hand, by local artisans. Really, I can't think of any other place in the world where you can get this kind of craftsmanship and artistry."

Whether working from his specially tricked-out truck in the burning heat of Morocco or from a chilly and drafty corrugated-metal workshop at Pinewood Studios, Hooper was the go-to guy for weapons. "For the film," Richard Hooper says, "everything was created from scratch, designed or concept-approved by the art department, the producer, the director or the actor, and then executed.

"The main design influence of the Persian weaponry came from research of sixth century design and also was influenced by the Prince of Persia video game," Richard Hooper continues. "I tried to find a balance between historic authenticity and fantasy, because Jerry Bruckheimer and Mike Newell wanted us to travel that fine line. We researched the collections in museums in Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt, the British Museum in London, the Smithsonian. And we found various books containing the armor and weapons of Persia at that time. We chose various styles and elements, then created our own designs of the swords, daggers and shields."

Richard Hooper and his department created nearly 3,500 individual items, including swords, shields, spears, axes, arrows, bows, quivers, scabbards, bow cases, daggers and Hassansin weapons. The weaponry was fabricated from iron, wood and rubber, or whatever was required for an individual scene. And like other creative department heads on the film, Richard Hooper would rely on the fine artisanship found in Morocco. "We utilised the great skills of the country's artisans," says Richard Hooper. "From leather workers to metal engravers and cloth makers, there are many skills which many have completely forgotten in developed countries like England and America."

Richard Hooper and his department created nearly 3,500 individual items, including swords, shields, spears, axes, arrows, bows, quivers, scabbards, bow cases, daggers and Hassansin weapons. The weaponry was fabricated from iron, wood and rubber, or whatever was required for an individual scene. And like other creative department heads on the film, Richard Hooper would rely on the fine artisanship found in Morocco. "We utilised the great skills of the country's artisans," says Richard Hooper. "From leather workers to metal engravers and cloth makers, there are many skills which many have completely forgotten in developed countries like England and America."

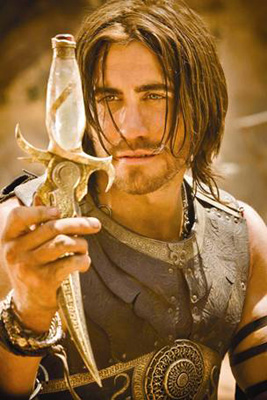

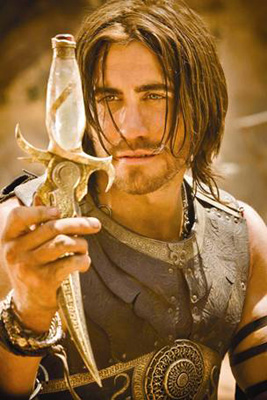

Of all the thousands of items under the domain of David Balfour, none was more important than the single most iconic object in the film: the Dagger of Time. As was the case with nearly everything in the movie, creating the final version of the Dagger of Time was a process of research, development and experimentation.

"Initially, we looked at an old-style Indian dagger as a model," says David Balfour, "but Jerry Bruckheimer wanted the Dagger to more closely resemble the one in the video game. The problem was when we turned the hilt of the Dagger from the game into something three-dimensional, it couldn't perform the functions that it had to do in the film. We had to do a bit of work to redesign the hilt, with its glass handle, metal filigree and jewel button on top that releases the sand from the blade.

"I think the end result was successful," continues David Balfour. "The handle is still elegant, as it was in the game, and we enhanced the blade with a lot of engraving." David Balfour created 20 different versions of the Dagger of Time, all identical but serving different functions. "The main, literal version actually has a metal blade," explains David Balfour. "It's fabricated from brass and is gold-plated. The weight is there, and it's picture-quality."

There was a considerable amount of maintenance that had to be constantly performed on this version of the Dagger, because of the film's many action sequences. "It's thrown around, kicked out of Dastan's hands, knocked into the dirt," says David Balfour. "There's a lot that goes on with the Dagger, so it's had its fair share of repairs. But we also had exact duplicates made in both hard and soft rubber for stunts and one that actually lights up."

The hard work made an impression on the cast. "When we went to Morocco in the first week, we visited some of the sets which had been built," recalls Gemma Arterton. "That was when I realised, 'Whoa, this is a big deal.' They were like cities. I'd never seen anything like it. You don't have to imagine anything. It's right there, and it's a real luxury, especially in these times of green screen. It was the world that really interested me in doing this film, and when you walk onto sets like ours, that world has already been created."

"Everywhere we looked, we saw the most exquisitely carved walls, drapes, ramparts," says Ben Kingsley. "And in Morocco, nature itself, the camels, thousands of horsemen, the dust. Our sets were so detailed that even if you're pausing, halfway in a line and just breathing in, the amount of energy and information you're breathing in is extraordinary. Hours and hours of work went into the environment. It's really uplifting and it honored our craft to such a degree."

The lunar-like landscape of Bouaissoun, 45 kilometers northwest of Marrakesh, was perfectly suited for Sheikh Amar's desert kingdom. The scenes involving his ostrich racetrack required four days of shooting with the temperamental birds. Ostriches have a reputation for being ornery, smelly, scary and dangerous, which might explain why the birds have rarely been featured on screen. "I never thought that ostriches would ever end up in one of my films," says Jerry Bruckheimer, "but it's a really funny and exciting sequence."

Brought in to supervise the extraordinary birds were ostrich experts Bill Rivers and Jennifer Henderson. Stunt coordinator George Aguilar and his team, with Rivers' assist, enlisted eight professional Moroccan jockeys to ride the ostriches in the racing sequences, requiring two solid weeks of training. "None of the jockeys ever rode an ostrich before," says Bill Rivers. "It's a lot different than riding a horse, because ostriches are not as stable. It takes a lot of practice. You also have to dismount properly so you don't get run over, kicked or stepped on."

Brought in to supervise the extraordinary birds were ostrich experts Bill Rivers and Jennifer Henderson. Stunt coordinator George Aguilar and his team, with Rivers' assist, enlisted eight professional Moroccan jockeys to ride the ostriches in the racing sequences, requiring two solid weeks of training. "None of the jockeys ever rode an ostrich before," says Bill Rivers. "It's a lot different than riding a horse, because ostriches are not as stable. It takes a lot of practice. You also have to dismount properly so you don't get run over, kicked or stepped on."

Alfred Molina portrayed the ostrich-adoring Sheikh Amar, and the actor did his best to get in character. Alfred Molina recalls: "I show off my ostrich Anita to Dastan and talk to him lovingly about this particular bird. These animals are very unpredictable and rather quixotic in their movements and decisions. I noticed Jennifer Henderson would constantly stroke their necks to keep them calm. So I thought, I'll try that, maybe it will help the scene.

"I was praying that Anita would be still, so I stroked her neck-which was actually very soft and sinewy-did the dialogue, and it went beautifully for two or three takes. And then, on one take-and I don't know what possessed me-but in the middle of the dialogue praising Anita, I just leaned forward and kissed her on the neck, thinking that I would either get my eye poked out or get away with it. And it went great! But at the end of the day, Jennifer Henderson told me that Anita, who I thought was a female, was actually Alan, a male. Hopefully, they'll create an MTV Award for that category."

The company next hit the road for the 200-kilometer, two-and-a-half-hour drive through the 7,415-foot Tizi n'Tichka pass in the High Atlas range, journeying southeast to Ouarzazate, the self-proclaimed "Hollywood of North Africa."

The call sheet of the first day of filming at the Little Fint oasis, 40 minutes outside of Ouarzazate, held two warnings, one more terrifying than the other: "Please do not touch the Ostrich on set today" and, even worse, "Beware- Snakes and Scoropions can be found at this location under and around the rocks. Be cautious."

There was nothing to fear, however, because Snake Dude (per his T-shirt) was on the case. This ever-smiling Moroccan man was greatly experienced in the ways of vipers and venomous beasties. He was responsible for clearing the shooting areas of the deadly pests before the cast and crew arrived and during shooting. It didn't take long for Snake Dude's glass jars to become filled with the pernicious creatures, all of which were released at the end of the workdays.

Two days into the location, high winds kicked up ferocious sandstorms followed by rain. "When we first scouted in Morocco," recalls Mike Newell, "there was a 50-mile-per hour wind blowing, but the locals would not dignify it with the name sandstorm. They said, 'This isn't a sandstorm, just a little breeze.' A sandstorm is a hell of a terrifying thing, because everything goes black-you can't see a thing-and it chokes you. And one of the great scenes in the movie takes place in a sandstorm."

Constant maintenance of equipment in such extreme weather conditions would bedevil Australian director of photography John Seale and his camera crew throughout filming in Morocco, but he had already experienced similar conditions shooting in Tunisia on The English Patient, for which he won an Academy Award®. "We were able to acclimatise to this heat, and the cameras were equipped for it," says John Seale. "But even so, we had a continual fogging of the negative. Its origin eluded us for weeks, but eventually we had to agree that it was the incredible heat that was fogging the film. Nothing we did could get rid of it. A lot of preparation went into the equipment. The dust storms and sand dervishes wreaked havoc with sand in the cameras, which can cause scratches and, consequently, reshoots, so the camera crew was particularly careful."

The next location for Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time was truly special. Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, the towering ancient ksar (fortified city) of Ait Ben Haddou was built with brown pisé (earth and rubble) tighremt (granary) structures designed with Berber motifs. Adjacent to the ksar was a perfect place for Wolf Kroeger to build the magnificent Nasaf marketplace, incorporating elements of Ait Ben Haddou in the background.

While filming in Ouarzazate, both the first and second units also shot within the extraordinary pisé walls of the Kasbah Taourirte, an ancient dwelling right in the center of town. In fact, the Kasbah was once all that existed of Ouarzazate, before the French overlords built their new garrison town around it, and it still has the beautiful and primitive atmosphere exuding strength and exoticism in equal measure. It's still the beating heart of Ouarzazate, its narrow alleyways teeming with residents coming and going, playing cards or dominoes, buying, selling and haggling in tiny shops.

After filming in the dramatic Tiwiyne Gorge, the company packed up and drove 322 kilometers due east along the Route of a Thousand Kasbahs to Erfoud. At a stone's throw from the Algerian border, the filmmakers selected a stretch of desert to serve as the forbidding entrance to the Valley of the Slaves, where Sheikh Amar and his raggedy bandits hold sway.

The final two days of filming in Morocco took place among the famed Merzouga Sand Dunes, mountains of sand rising like a golden-hued mirage to heights of 450 feet from a black, rocky, unforgiving plain. "I think it's really appropriate that a movie titled Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time ends its Morocco shoot in sand dunes," said executive producer Eric McLeod. These are the classic dunes of every Arabian Nights fantasy, sculpted, shaped and rippled by the hot winds, their colors changing with the movement of the sun. On the final day in Morocco, the thermometer topped out at 125 degrees Fahrenheit. Crew members from the Western Hemisphere wrapped themselves in indigo Tuareg head coverings and went shoeless to make walking easier among the deep dunes.

"My DNA now has the Moroccan desert in it, because I definitely breathed in my share of sand," says Jake Gyllenhaal. "I grew up in Southern California, and the weather and topography of Morocco are actually quite similar, so it wasn't too rough for me. I had shot here before, but I'd never actually gone as far into the desert and seen as much of Morocco as I did on Prince of Persia. It's a really beautiful country. There were times, on off days, when I'd just drive and drive, just amazed at the landscapes and the culture. Moroccan people are the sweetest, kindest people, and the hardest workers."

Filming in Cooler, Calmer Great Britain: Filmmakers create a magical world on pinewood studios sound stages

Filming in Cooler, Calmer Great Britain: Filmmakers create a magical world on pinewood studios sound stages

The sudden transition from ruthlessly hot and routinely chaotic Morocco to the staid, cool, controlled confines of Pinewood Studios was a kind of culture shock for the company. The fully fabricated but no less wondrous sets designed by Wolf Kroeger were constructed on nine soundstages of the historic studio in the bucolic burg of Iver Heath in Buckinghamshire.

"There's nothing better than being in a real environment, being in a place where you feel like you go back centuries," says Jake Gyllenhaal. "When we were filming in Morocco, we were all in the middle of the desert, dirty and dusty. I can't recall the amount of times between takes you had to just get the sand out of your eyes, mouth and ears so you looked like you weren't literally made of sand. The realism of it all was indelible. But onstage in London, we could mix reality with fantasy, which is all the more interesting towatch."

At Pinewood, the company settled into a routine utterly different from what they had experienced in Morocco. It was more predictable, more controllable and certainly cooler. "It's as if you're running a long race and Morocco was the uphill part," says executive producer Patrick McCormick. "We could walk from one location to the next just by going from one soundstage to another, and we didn't have weather to contend with. And instead of catering an average of 700 people a day, we dropped down to just 250 or 300. In Morocco, we had 300 drivers alone!"

While the company was filming in Morocco, U.K. supervising art director Gary Freeman's team of art department and construction personnel were readying 35 complex sets on nine soundstages.

The jaw-dropping Eastern Gate of Alamut occupied nearly the entire length, breadth and height of the 007 Stage at Pinewood, with walls nearly 50 feet high and palm trees imported from southern Spain and then carefully maintained by greensman Jon Marson and his team. The set was large enough for the filming of a massive battle scene involving hundreds of extras and 25 horses charging through gates and barriers of fire. "The primary reason for building this set was for night work involving lots of parkour and other stuntwork, which would have been difficult to shoot in Morocco," says Freeman. U.K. construction manager Brian Neighbour built the Alamut Eastern Gate complex in just 14 weeks, utilising 3,000 sheets of 8x4 and 70,000 feet of 3x1 timber, as well as 40 tons of casting plaster for the moldings.

The Alamut Great Hall on S Stage was a lustrous amalgamation of Indian styles, all in cream tones with flecks of gold. "I didn't want to use candlelight for this set," says set decorator Elli Griff. "I was determined to use only oil light, which turned out to be a bit of a feat. But John Seale, our cinematographer, felt that he got interesting light from it. I used jeweled colors, low-level dressing, canopies and things of that nature that could reflect the light."

The versatile Alamut Palace interior was utilised for several environments, including Tamina's throne room, Tus' chambers and the banquet room in which King Sharaman is assassinated. "I wanted to make the base of Tamina's throne a crystal lotus flower, which almost subconsciously links to the crystalline Sandglass of the Gods," says Elli Griff.

"She has a huge, golden canopy above her throne with a hole in it so that the light can come down as if she has a direct connection with the gods and heaven. Everything about Tamina and her culture is accepting, soft and humorous."

A sumptuous fantasia of color, with its peacock bed and wall ornamentation resembling ancient illuminated manuscripts, inlaid with precious jewels, Tamina's chambers is a bedroom truly befitting a princess. "Mike Newell and Wolf Kroeger had a discussion in which they decided that Tamina's boudoir needed to be a fantastic, very feminine space," says Gary Freeman.

"You have to do something that just begs belief, that's surreal and opulent," adds Elli Griff. "Tamina's bedroom is very jewel-encrusted so that the low-level lights would cast an enchanted glow."

Constructed on the same soundstage as the Alamut Palace interior and Tamina's chamber was the Sky Chamber, an aerie high above Alamut where the sacred Dagger of Time is kept in a beautifully designed tabernacle. With its carved wooden statuary and stone pillars-all of the figures were hand-carved, then molded and cast-it has a temple like feeling, which was accentuated during filming by cinematographer John Seale's artful shafts of light illuminating the object with a spiritual glow. The Alamut Temple Garden was an intentionally idyllic slice of paradise, with lorikeets, macaws, parrots and toucans in ornate cages, topiary elephants, a working fountain decorated with colorful statues of unicorns, rams and peacocks, an arch with jewel-encrusted frescoes, trees with pale, translucent leaves (each one meticulously applied by hand), golden lanterns and small, tinkling bells.

"Wolf wanted to steer away from a purely realistic period garden," says Gary Freeman. "Since it's for one of the most important scenes of the movie, he wanted to make it kind of a magic garden, using several Russian expressionist artists for inspiration."

Other major sets constructed at Pinewood included the Temple of the Dagger, a cave with waterfalls spilling into a pool, and a shrine bedecked with treasures and spiritual offerings-the site of a major action sequence with Jake Gyllenhaal, Gemma Arterton and Thomas Dupont as Hassad, the whip-blade Hassansin. The interior had to tangentially match exteriors shot in Oukaimden back in Morocco. Sets were also constructed in great detail replicating the Avrat Bazaar, as well as streets and rooftops of the city, all designed for thrilling parkour action.

"We knew from day one that there was a key action sequence that needed to be filmed on this set featuring lots of parkour," says Gary Freeman. "Wolf Kroeger wanted to create a series of vertical and horizontal structures which could contain the acrobatics. We took a team of plasterers to Morocco to get the textures as true as possible, and they took molds for the wall finishes. The real difficulty was in reinforcing the walls for the stunt players, so there's lots of metal hiding beneath the earthen structures."

Dressing Persia: Costume designer Penny Rose cuts a rug, literally

A nondescript street in a Marrakesh neighborhood known as the Zone Industrielle has a building that could be a warehouse or factory. But in the months leading up to the filming of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, and during the duration of its Morocco shoot, this building was a dream factory, housing a small army of cutters, costumers, cobblers, seamstresses, milliners, dyers, armorers and artisans, all working under the supervision of costume designer Penny Rose.

"There's no one in her field like Penny Rose," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who enlisted her for the entire Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy. "Her attention to detail almost defies description, and her ability to find the exact right costumes to define characters is fantastic. Penny Rose can organise anything, anywhere in the world. She's a tough taskmaster, but we love her artistry."

"Orientalist paintings were part of the influence," says Penny Rose. "Most of those images were painted in Victorian times, so they're 19th-century impressions of scenes from hundreds of years previous to that. The scale of the Orientalist pictures was the most significant thing to us: the shapes of the garments, the flowing cloaks, the amount of people crushed into small spaces."

For Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Penny Rose had to create no fewer than 7,000 costumes, nearly all of them built from scratch. Assisting Penny Rose were assistant costume designers Timothy John Norster, Margie Fortune and Maria Tortu, as well as costume supervisor Ken Crouch, costume designer assistant Lucy Bowring and wardrobe master Mark Holmes. Rose also relied on a veritable army of wardrobe masters, on-set costumers, workshop supervisors, dyers, metalworkers, shoemakers and artisans from all over the world.

Another trick of Penny Rose's trade, unimaginable to those outside the craft, is the breakdown department. "Very few people on the films I do go to set in a new costume," explains Penny Rose. "We always have to break it down first. I want costumes to look real, even in a fantasy film like this. Our breakdown department employed tools like a cement mixer. Once the leather goods are newly made, we put them in the cement mixer for a couple of hours with a few stones, and they come out looking well used. They also use cheese graters to distress costumes, believe it or not."

To obtain the materials for so many thousands of costumes, Penny Rose scoured the four corners of the globe, discovering fabrics from as far away as Turkey, Thailand, Afghanistan, China, Malaysia, Great Britain, Paris, Rome and, of course, Morocco. These materials were then utilised in surprising ways. For example, to create Sheikh Amar's shabby but colorful coat, Rose fabricated it from three Indian bedspreads sewn together.

"Then we took a cheese grater to it until we got this fantastic ragged look, revealing layers of different fabrics, colors, and designs," says Penny Rose. "The sheikh also has a headdress, and his boots are made from an old carpet."

Highly Visual Effects Complete the Picture: Filmmakers look to the pros for rewinds and extensions

"Just when you think that you've seen just about everything," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, "we stand visual effects on their ear and do things that haven't been seen before. Hopefully, what you'll see on screen in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time will be something fresh, interesting and innovative."

Tom Wood and his extensive team of producers, managers, coordinators, data wranglers, and technicians were called upon to create nearly 1,200 visual-effects shots for the film. Some were long and involved-such as the time rewinds, the massive sandstorm in the climactic sequence at the Sandglass of the Gods, and the Lead Hassansin's vicious pit vipers-and some were minor little fixes at the edge of a frame.

Tom Wood enlisted all of the modern technologies and techniques at his command. Among the most important effects for Wood were the four time rewinds, caused when the jewel on the hilt of the dagger is pushed, releasing the Sands of Time. "We decided immediately that we couldn't just run the film backwards," explains Tom Wood. "We didn't want it to look like a VCR rewind. We had to develop an original and visually interesting approach. What we aimed for was a kind of slit-scan effect where everything would be warped by time and space.

"What we've done for the time rewind was designed by the visual-effects house Double Negative," Tom Wood continues. "They call it 'event capture.' We pre-visualised the sequence thoroughly with 'animatics' resembling animated storyboards. We then came onto the main unit set and shot the forward-running action, followed by four days of effects coverage, putting cameras in the positions that we wanted to capture the shot from.

"We have nine Arriflex 435 cameras shooting with identical lenses, up to 48 frames a second at a 45-degree shutter angle, which has caused a lot of challenges with relighting the set," Tom Wood continues. "That's to get as sharp an image as possible. We have a number of people from Double Negative who have laid out the cameras each time, surveyed into position. They have to be very precise. It takes about two hours to set up each array of cameras.

"We had to have our principal actors do 20 minutes of acting, go away for two hours, come back for another 20 minutes, and remember where they were. It's a challenge, trying to keep it fresh for each time that we see it."

The arduous filming of the time rewind sequences obviously challenged the actors' abilities of recall and concentration. "I'd never done visual-effects sequences before, and it's a really, really long process," admits Gemma Arterton. "But when you see it, it looks magical, adding a whole other dimension to the film."

Director: Mike Newell

Genre: Action, Adventure, Fantasy

Rated: PG

Running Time: 111 minutes

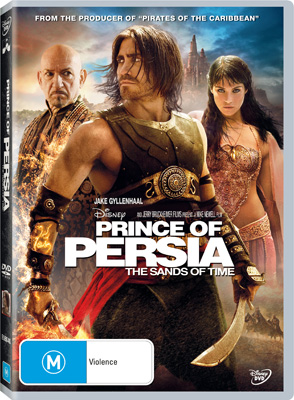

Synopsis: From the team that brought the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy to the big screen, Walt Disney Pictures and Jerry Bruckheimer Films present Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, an epic action-adventure set in the mystical lands of Persia. A rogue prince (Jake Gyllenhaal) reluctantly joins forces with a mysterious princess (Gemma Arterton) and together, they race against dark forces to safeguard an ancient dagger capable of releasing the Sands of Time-a gift from the gods that can reverse time and allow its possessor to rule the world.

Release Date: May 27th, 2010

Website: www.princeofpersiamovie.com.au

"Everybody said to us, 'Morocco's a great place,'" recalls director Mike Newell. "'Just don't go there in July and August.' So of course, we shot all the way through July and August."

"I couldn't understand why my hotel was empty when I got to Morocco," says Alfred Molina. "I kept thinking, isn't everybody in Europe on holiday in August? And the local people were looking at me as if to say, What are you doing here? And then I quickly discovered that you don't go to Morocco, 'cause it's too bloody hot! Nobody works in Morocco in August. So, yeah, mad dogs and Englishmen, I guess."

"It makes perfect sense to film a movie about the ancient world in Morocco," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, "because the ancient and the modern coexist side by side. Even with chic restaurants, elegant clubs and boutique hotels springing up all over Marrakesh, artisans in the medina are still hand-tooling their products just as they have for thousands of years. And outside of the cities, life is even more traditional amidst Morocco's mountains and valleys, plains and deserts. With so many films having been made there, there's a great infrastructure with skilled technicians and workers, and the Moroccan government is always very welcoming. Moroccans are great craftsmen, and we used an enormous number of artisans. They did an amazing job."

Cast and crew braved temperatures in excess of 120 degrees Fahrenheit, high altitudes, countless lamb burgers and lethal critters in harsh desert landscapes. Following six months of active preparation, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time began principal photography on July 23, 2008, in suitably epic fashion, with the first two weeks of filming occurring at an altitude of 8,200 feet in Oukaimden, 75 kilometers above the sizzling hot city of Marrakesh. To access this remote location in the High Atlas range, one had to ride through the verdant Ourika Valley and then ascend a winding, rustic mountain road with perilous drops and switchbacks. But it was a perfect site for the film's Hidden Valley location.

It took 20 Moroccan laborers three and a half weeks to build a road into the secluded location. Meanwhile, the first of many base camps that included a massive catering tent and cooking facilities was created, plus all of the production vehicles-from the actors' trailers to tech trucks. An armada of four-wheel-drive Land Rovers was brought in by Morocco transportation coordinator Gerry Gore to ferry the company from the base camp at the foot of the ski lift to the Hidden Valley site-a ride bumpy enough to compete with the Indiana Jones attraction at Disneyland.

Temperatures in midsummer in North Africa rarely drop below 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and during shooting, the average loomed at about 110-115 degrees. During many days of the shoot, the Moroccan locations were either the hottest places on Earth, or something very close to it.

Approximately 18 miles north of Izergane is a flat, dusty, windless stretch of desert called Agafay, where nearly 500 background players portrayed a large chunk of the Persian army as it approaches Alamut. The film's technical and security adviser Harry Humphries and his Moroccan associate Lotfi Saalaoui (a police officer assigned to work with the film's security team) trained the hundreds of local extras. Humphries, a former Navy SEAL and longtime Jerry Bruckheimer associate is one of the motion-picture industry's most experienced technical, military and security advisers. "We had to turn 400 people into a marching army within a very short period of time," says Harry Humphries. "Luckily, Sergeant Lotfi is an excellent drill sergeant, so although none of the extras had ever seen a drill field before, he turned them into an excellent marching force in just three days."

Approximately 18 miles north of Izergane is a flat, dusty, windless stretch of desert called Agafay, where nearly 500 background players portrayed a large chunk of the Persian army as it approaches Alamut. The film's technical and security adviser Harry Humphries and his Moroccan associate Lotfi Saalaoui (a police officer assigned to work with the film's security team) trained the hundreds of local extras. Humphries, a former Navy SEAL and longtime Jerry Bruckheimer associate is one of the motion-picture industry's most experienced technical, military and security advisers. "We had to turn 400 people into a marching army within a very short period of time," says Harry Humphries. "Luckily, Sergeant Lotfi is an excellent drill sergeant, so although none of the extras had ever seen a drill field before, he turned them into an excellent marching force in just three days."Twenty kilometers southwest of Marrakesh, Tamesloht is a dusty, unpaved village consisting of a few shops, some humble dwellings, a gendarme station, friendly townspeople and walls of an ancient kasbah reputed to be 700 years old. It was chosen as the site for the film's fictitious city of Alamut, as designed by Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time production designer Wolf Kroeger. The imaginary locale features a magnificent square with a Taj Mahal-like palace rising 50 feet above the ground, an adjacent red-andwhite structure festooned with balconies, and a central fountain spouting water-all flanked by elephant statues. Streets abound with architectural and decorative detail: scroll shops in a narrow alley bedecked by small, tinkling bells, a pale yellow temple adorned with garlands of vividly colored flowers, arches carved with floral designs in bas relief, plus stalls selling shoes, dried herbs and flowers, and ancient mud walls festooned with imaginative frescoes of men and beasts. "There aren't many sets," says screenwriter Carlo Bernard, "that are so big that you can actually get lost in them!"

"Wolf Kroeger is a real artist," says Jerry Bruckheimer. "He has great vision, amazing attention to detail, and isn't afraid to think big and build big."

Mike Newell agrees: "Wolf Kroeger has a wonderful ability to tune himself. He's fantastic with two things: one is the big overall concept, and the other is expressing the concept through minute detail. He has a painterly eye, and, like myself, he was inspired by Orientalist art. But Wolf Kroeger also did an enormous amount of research into ancient Persian and Near Eastern architecture. We spent days and days looking at pictures of Iran."

Wolf Kroeger's creations for Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time weren't just sets, but complete environments that enveloped the cast and created an alternate world that combined history and fantasy with truly unleashed imagination. Working alongside Wolf Kroeger were supervising art director Jonathan McKinstry (for Morocco), supervising art director Gary Freeman (U.K.), set decorator Elli Griff, prop master David Balfour, armorer Richard Hooper, construction managers John Maher (Morocco) and Brian Neighbour (U.K.), and an entire army of artists and technicians.

The version of pre-Islamic, sixth-century Persia created by Wolf Kroeger and his cohorts comes from a deliberate attempt to interweave authentic architecture and meticulously researched design elements with a high degree of fantasy, as dictated by the fanciful and supernatural element in the story. Alamut is entirely fictitious, a kind of Shangri-la, with a noticeable Indian influence. "From a design point of view," says Jonathan McKinstry, "the sets, set dressing and props are historical-looking pieces. However, because we're not making a factual historical film, we haven't locked ourselves into any one particular style.

And since we are relying on a lot of Moroccan locations, there's admittedly some North African flavor in the designs as well."

Every design department would rely heavily on the extraordinary skills of Moroccan artisans, craftsmen and builders. Nearly every single piece required by Griff's setdecorating team, David Balfour's prop department and Hooper's armory crew was made in massive workshops in the Marrakesh industrial zone. Items like King Sharaman's ornate horse-drawn hearse and the overweight Mughal's palanquin were created and constructed by Stuart Rose. "Visiting the set-decoration and props warehouses was one of the most amazing experiences I've had on any location of any of our movies," says executive producer Chad Oman. "They were gigantic warehouses filled floor to ceiling with props and production-design elements, from lamps to swords to saddles to all sorts of elaborate weaponry-all of it made right there on the spot, by hand, by local artisans. Really, I can't think of any other place in the world where you can get this kind of craftsmanship and artistry."

Whether working from his specially tricked-out truck in the burning heat of Morocco or from a chilly and drafty corrugated-metal workshop at Pinewood Studios, Hooper was the go-to guy for weapons. "For the film," Richard Hooper says, "everything was created from scratch, designed or concept-approved by the art department, the producer, the director or the actor, and then executed.

"The main design influence of the Persian weaponry came from research of sixth century design and also was influenced by the Prince of Persia video game," Richard Hooper continues. "I tried to find a balance between historic authenticity and fantasy, because Jerry Bruckheimer and Mike Newell wanted us to travel that fine line. We researched the collections in museums in Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt, the British Museum in London, the Smithsonian. And we found various books containing the armor and weapons of Persia at that time. We chose various styles and elements, then created our own designs of the swords, daggers and shields."

Richard Hooper and his department created nearly 3,500 individual items, including swords, shields, spears, axes, arrows, bows, quivers, scabbards, bow cases, daggers and Hassansin weapons. The weaponry was fabricated from iron, wood and rubber, or whatever was required for an individual scene. And like other creative department heads on the film, Richard Hooper would rely on the fine artisanship found in Morocco. "We utilised the great skills of the country's artisans," says Richard Hooper. "From leather workers to metal engravers and cloth makers, there are many skills which many have completely forgotten in developed countries like England and America."

Richard Hooper and his department created nearly 3,500 individual items, including swords, shields, spears, axes, arrows, bows, quivers, scabbards, bow cases, daggers and Hassansin weapons. The weaponry was fabricated from iron, wood and rubber, or whatever was required for an individual scene. And like other creative department heads on the film, Richard Hooper would rely on the fine artisanship found in Morocco. "We utilised the great skills of the country's artisans," says Richard Hooper. "From leather workers to metal engravers and cloth makers, there are many skills which many have completely forgotten in developed countries like England and America."Of all the thousands of items under the domain of David Balfour, none was more important than the single most iconic object in the film: the Dagger of Time. As was the case with nearly everything in the movie, creating the final version of the Dagger of Time was a process of research, development and experimentation.

"Initially, we looked at an old-style Indian dagger as a model," says David Balfour, "but Jerry Bruckheimer wanted the Dagger to more closely resemble the one in the video game. The problem was when we turned the hilt of the Dagger from the game into something three-dimensional, it couldn't perform the functions that it had to do in the film. We had to do a bit of work to redesign the hilt, with its glass handle, metal filigree and jewel button on top that releases the sand from the blade.

"I think the end result was successful," continues David Balfour. "The handle is still elegant, as it was in the game, and we enhanced the blade with a lot of engraving." David Balfour created 20 different versions of the Dagger of Time, all identical but serving different functions. "The main, literal version actually has a metal blade," explains David Balfour. "It's fabricated from brass and is gold-plated. The weight is there, and it's picture-quality."

There was a considerable amount of maintenance that had to be constantly performed on this version of the Dagger, because of the film's many action sequences. "It's thrown around, kicked out of Dastan's hands, knocked into the dirt," says David Balfour. "There's a lot that goes on with the Dagger, so it's had its fair share of repairs. But we also had exact duplicates made in both hard and soft rubber for stunts and one that actually lights up."

The hard work made an impression on the cast. "When we went to Morocco in the first week, we visited some of the sets which had been built," recalls Gemma Arterton. "That was when I realised, 'Whoa, this is a big deal.' They were like cities. I'd never seen anything like it. You don't have to imagine anything. It's right there, and it's a real luxury, especially in these times of green screen. It was the world that really interested me in doing this film, and when you walk onto sets like ours, that world has already been created."

"Everywhere we looked, we saw the most exquisitely carved walls, drapes, ramparts," says Ben Kingsley. "And in Morocco, nature itself, the camels, thousands of horsemen, the dust. Our sets were so detailed that even if you're pausing, halfway in a line and just breathing in, the amount of energy and information you're breathing in is extraordinary. Hours and hours of work went into the environment. It's really uplifting and it honored our craft to such a degree."

The lunar-like landscape of Bouaissoun, 45 kilometers northwest of Marrakesh, was perfectly suited for Sheikh Amar's desert kingdom. The scenes involving his ostrich racetrack required four days of shooting with the temperamental birds. Ostriches have a reputation for being ornery, smelly, scary and dangerous, which might explain why the birds have rarely been featured on screen. "I never thought that ostriches would ever end up in one of my films," says Jerry Bruckheimer, "but it's a really funny and exciting sequence."

Brought in to supervise the extraordinary birds were ostrich experts Bill Rivers and Jennifer Henderson. Stunt coordinator George Aguilar and his team, with Rivers' assist, enlisted eight professional Moroccan jockeys to ride the ostriches in the racing sequences, requiring two solid weeks of training. "None of the jockeys ever rode an ostrich before," says Bill Rivers. "It's a lot different than riding a horse, because ostriches are not as stable. It takes a lot of practice. You also have to dismount properly so you don't get run over, kicked or stepped on."

Brought in to supervise the extraordinary birds were ostrich experts Bill Rivers and Jennifer Henderson. Stunt coordinator George Aguilar and his team, with Rivers' assist, enlisted eight professional Moroccan jockeys to ride the ostriches in the racing sequences, requiring two solid weeks of training. "None of the jockeys ever rode an ostrich before," says Bill Rivers. "It's a lot different than riding a horse, because ostriches are not as stable. It takes a lot of practice. You also have to dismount properly so you don't get run over, kicked or stepped on."Alfred Molina portrayed the ostrich-adoring Sheikh Amar, and the actor did his best to get in character. Alfred Molina recalls: "I show off my ostrich Anita to Dastan and talk to him lovingly about this particular bird. These animals are very unpredictable and rather quixotic in their movements and decisions. I noticed Jennifer Henderson would constantly stroke their necks to keep them calm. So I thought, I'll try that, maybe it will help the scene.

"I was praying that Anita would be still, so I stroked her neck-which was actually very soft and sinewy-did the dialogue, and it went beautifully for two or three takes. And then, on one take-and I don't know what possessed me-but in the middle of the dialogue praising Anita, I just leaned forward and kissed her on the neck, thinking that I would either get my eye poked out or get away with it. And it went great! But at the end of the day, Jennifer Henderson told me that Anita, who I thought was a female, was actually Alan, a male. Hopefully, they'll create an MTV Award for that category."

The company next hit the road for the 200-kilometer, two-and-a-half-hour drive through the 7,415-foot Tizi n'Tichka pass in the High Atlas range, journeying southeast to Ouarzazate, the self-proclaimed "Hollywood of North Africa."

The call sheet of the first day of filming at the Little Fint oasis, 40 minutes outside of Ouarzazate, held two warnings, one more terrifying than the other: "Please do not touch the Ostrich on set today" and, even worse, "Beware- Snakes and Scoropions can be found at this location under and around the rocks. Be cautious."

There was nothing to fear, however, because Snake Dude (per his T-shirt) was on the case. This ever-smiling Moroccan man was greatly experienced in the ways of vipers and venomous beasties. He was responsible for clearing the shooting areas of the deadly pests before the cast and crew arrived and during shooting. It didn't take long for Snake Dude's glass jars to become filled with the pernicious creatures, all of which were released at the end of the workdays.

Two days into the location, high winds kicked up ferocious sandstorms followed by rain. "When we first scouted in Morocco," recalls Mike Newell, "there was a 50-mile-per hour wind blowing, but the locals would not dignify it with the name sandstorm. They said, 'This isn't a sandstorm, just a little breeze.' A sandstorm is a hell of a terrifying thing, because everything goes black-you can't see a thing-and it chokes you. And one of the great scenes in the movie takes place in a sandstorm."

Constant maintenance of equipment in such extreme weather conditions would bedevil Australian director of photography John Seale and his camera crew throughout filming in Morocco, but he had already experienced similar conditions shooting in Tunisia on The English Patient, for which he won an Academy Award®. "We were able to acclimatise to this heat, and the cameras were equipped for it," says John Seale. "But even so, we had a continual fogging of the negative. Its origin eluded us for weeks, but eventually we had to agree that it was the incredible heat that was fogging the film. Nothing we did could get rid of it. A lot of preparation went into the equipment. The dust storms and sand dervishes wreaked havoc with sand in the cameras, which can cause scratches and, consequently, reshoots, so the camera crew was particularly careful."

The next location for Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time was truly special. Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, the towering ancient ksar (fortified city) of Ait Ben Haddou was built with brown pisé (earth and rubble) tighremt (granary) structures designed with Berber motifs. Adjacent to the ksar was a perfect place for Wolf Kroeger to build the magnificent Nasaf marketplace, incorporating elements of Ait Ben Haddou in the background.

While filming in Ouarzazate, both the first and second units also shot within the extraordinary pisé walls of the Kasbah Taourirte, an ancient dwelling right in the center of town. In fact, the Kasbah was once all that existed of Ouarzazate, before the French overlords built their new garrison town around it, and it still has the beautiful and primitive atmosphere exuding strength and exoticism in equal measure. It's still the beating heart of Ouarzazate, its narrow alleyways teeming with residents coming and going, playing cards or dominoes, buying, selling and haggling in tiny shops.

After filming in the dramatic Tiwiyne Gorge, the company packed up and drove 322 kilometers due east along the Route of a Thousand Kasbahs to Erfoud. At a stone's throw from the Algerian border, the filmmakers selected a stretch of desert to serve as the forbidding entrance to the Valley of the Slaves, where Sheikh Amar and his raggedy bandits hold sway.

The final two days of filming in Morocco took place among the famed Merzouga Sand Dunes, mountains of sand rising like a golden-hued mirage to heights of 450 feet from a black, rocky, unforgiving plain. "I think it's really appropriate that a movie titled Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time ends its Morocco shoot in sand dunes," said executive producer Eric McLeod. These are the classic dunes of every Arabian Nights fantasy, sculpted, shaped and rippled by the hot winds, their colors changing with the movement of the sun. On the final day in Morocco, the thermometer topped out at 125 degrees Fahrenheit. Crew members from the Western Hemisphere wrapped themselves in indigo Tuareg head coverings and went shoeless to make walking easier among the deep dunes.

"My DNA now has the Moroccan desert in it, because I definitely breathed in my share of sand," says Jake Gyllenhaal. "I grew up in Southern California, and the weather and topography of Morocco are actually quite similar, so it wasn't too rough for me. I had shot here before, but I'd never actually gone as far into the desert and seen as much of Morocco as I did on Prince of Persia. It's a really beautiful country. There were times, on off days, when I'd just drive and drive, just amazed at the landscapes and the culture. Moroccan people are the sweetest, kindest people, and the hardest workers."

Filming in Cooler, Calmer Great Britain: Filmmakers create a magical world on pinewood studios sound stages

Filming in Cooler, Calmer Great Britain: Filmmakers create a magical world on pinewood studios sound stagesThe sudden transition from ruthlessly hot and routinely chaotic Morocco to the staid, cool, controlled confines of Pinewood Studios was a kind of culture shock for the company. The fully fabricated but no less wondrous sets designed by Wolf Kroeger were constructed on nine soundstages of the historic studio in the bucolic burg of Iver Heath in Buckinghamshire.

"There's nothing better than being in a real environment, being in a place where you feel like you go back centuries," says Jake Gyllenhaal. "When we were filming in Morocco, we were all in the middle of the desert, dirty and dusty. I can't recall the amount of times between takes you had to just get the sand out of your eyes, mouth and ears so you looked like you weren't literally made of sand. The realism of it all was indelible. But onstage in London, we could mix reality with fantasy, which is all the more interesting towatch."

At Pinewood, the company settled into a routine utterly different from what they had experienced in Morocco. It was more predictable, more controllable and certainly cooler. "It's as if you're running a long race and Morocco was the uphill part," says executive producer Patrick McCormick. "We could walk from one location to the next just by going from one soundstage to another, and we didn't have weather to contend with. And instead of catering an average of 700 people a day, we dropped down to just 250 or 300. In Morocco, we had 300 drivers alone!"

While the company was filming in Morocco, U.K. supervising art director Gary Freeman's team of art department and construction personnel were readying 35 complex sets on nine soundstages.

The jaw-dropping Eastern Gate of Alamut occupied nearly the entire length, breadth and height of the 007 Stage at Pinewood, with walls nearly 50 feet high and palm trees imported from southern Spain and then carefully maintained by greensman Jon Marson and his team. The set was large enough for the filming of a massive battle scene involving hundreds of extras and 25 horses charging through gates and barriers of fire. "The primary reason for building this set was for night work involving lots of parkour and other stuntwork, which would have been difficult to shoot in Morocco," says Freeman. U.K. construction manager Brian Neighbour built the Alamut Eastern Gate complex in just 14 weeks, utilising 3,000 sheets of 8x4 and 70,000 feet of 3x1 timber, as well as 40 tons of casting plaster for the moldings.

The Alamut Great Hall on S Stage was a lustrous amalgamation of Indian styles, all in cream tones with flecks of gold. "I didn't want to use candlelight for this set," says set decorator Elli Griff. "I was determined to use only oil light, which turned out to be a bit of a feat. But John Seale, our cinematographer, felt that he got interesting light from it. I used jeweled colors, low-level dressing, canopies and things of that nature that could reflect the light."

The versatile Alamut Palace interior was utilised for several environments, including Tamina's throne room, Tus' chambers and the banquet room in which King Sharaman is assassinated. "I wanted to make the base of Tamina's throne a crystal lotus flower, which almost subconsciously links to the crystalline Sandglass of the Gods," says Elli Griff.

"She has a huge, golden canopy above her throne with a hole in it so that the light can come down as if she has a direct connection with the gods and heaven. Everything about Tamina and her culture is accepting, soft and humorous."

A sumptuous fantasia of color, with its peacock bed and wall ornamentation resembling ancient illuminated manuscripts, inlaid with precious jewels, Tamina's chambers is a bedroom truly befitting a princess. "Mike Newell and Wolf Kroeger had a discussion in which they decided that Tamina's boudoir needed to be a fantastic, very feminine space," says Gary Freeman.

"You have to do something that just begs belief, that's surreal and opulent," adds Elli Griff. "Tamina's bedroom is very jewel-encrusted so that the low-level lights would cast an enchanted glow."

Constructed on the same soundstage as the Alamut Palace interior and Tamina's chamber was the Sky Chamber, an aerie high above Alamut where the sacred Dagger of Time is kept in a beautifully designed tabernacle. With its carved wooden statuary and stone pillars-all of the figures were hand-carved, then molded and cast-it has a temple like feeling, which was accentuated during filming by cinematographer John Seale's artful shafts of light illuminating the object with a spiritual glow. The Alamut Temple Garden was an intentionally idyllic slice of paradise, with lorikeets, macaws, parrots and toucans in ornate cages, topiary elephants, a working fountain decorated with colorful statues of unicorns, rams and peacocks, an arch with jewel-encrusted frescoes, trees with pale, translucent leaves (each one meticulously applied by hand), golden lanterns and small, tinkling bells.

"Wolf wanted to steer away from a purely realistic period garden," says Gary Freeman. "Since it's for one of the most important scenes of the movie, he wanted to make it kind of a magic garden, using several Russian expressionist artists for inspiration."

Other major sets constructed at Pinewood included the Temple of the Dagger, a cave with waterfalls spilling into a pool, and a shrine bedecked with treasures and spiritual offerings-the site of a major action sequence with Jake Gyllenhaal, Gemma Arterton and Thomas Dupont as Hassad, the whip-blade Hassansin. The interior had to tangentially match exteriors shot in Oukaimden back in Morocco. Sets were also constructed in great detail replicating the Avrat Bazaar, as well as streets and rooftops of the city, all designed for thrilling parkour action.

"We knew from day one that there was a key action sequence that needed to be filmed on this set featuring lots of parkour," says Gary Freeman. "Wolf Kroeger wanted to create a series of vertical and horizontal structures which could contain the acrobatics. We took a team of plasterers to Morocco to get the textures as true as possible, and they took molds for the wall finishes. The real difficulty was in reinforcing the walls for the stunt players, so there's lots of metal hiding beneath the earthen structures."

Dressing Persia: Costume designer Penny Rose cuts a rug, literally

A nondescript street in a Marrakesh neighborhood known as the Zone Industrielle has a building that could be a warehouse or factory. But in the months leading up to the filming of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, and during the duration of its Morocco shoot, this building was a dream factory, housing a small army of cutters, costumers, cobblers, seamstresses, milliners, dyers, armorers and artisans, all working under the supervision of costume designer Penny Rose.

"There's no one in her field like Penny Rose," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who enlisted her for the entire Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy. "Her attention to detail almost defies description, and her ability to find the exact right costumes to define characters is fantastic. Penny Rose can organise anything, anywhere in the world. She's a tough taskmaster, but we love her artistry."

"Orientalist paintings were part of the influence," says Penny Rose. "Most of those images were painted in Victorian times, so they're 19th-century impressions of scenes from hundreds of years previous to that. The scale of the Orientalist pictures was the most significant thing to us: the shapes of the garments, the flowing cloaks, the amount of people crushed into small spaces."

For Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Penny Rose had to create no fewer than 7,000 costumes, nearly all of them built from scratch. Assisting Penny Rose were assistant costume designers Timothy John Norster, Margie Fortune and Maria Tortu, as well as costume supervisor Ken Crouch, costume designer assistant Lucy Bowring and wardrobe master Mark Holmes. Rose also relied on a veritable army of wardrobe masters, on-set costumers, workshop supervisors, dyers, metalworkers, shoemakers and artisans from all over the world.

Another trick of Penny Rose's trade, unimaginable to those outside the craft, is the breakdown department. "Very few people on the films I do go to set in a new costume," explains Penny Rose. "We always have to break it down first. I want costumes to look real, even in a fantasy film like this. Our breakdown department employed tools like a cement mixer. Once the leather goods are newly made, we put them in the cement mixer for a couple of hours with a few stones, and they come out looking well used. They also use cheese graters to distress costumes, believe it or not."

To obtain the materials for so many thousands of costumes, Penny Rose scoured the four corners of the globe, discovering fabrics from as far away as Turkey, Thailand, Afghanistan, China, Malaysia, Great Britain, Paris, Rome and, of course, Morocco. These materials were then utilised in surprising ways. For example, to create Sheikh Amar's shabby but colorful coat, Rose fabricated it from three Indian bedspreads sewn together.

"Then we took a cheese grater to it until we got this fantastic ragged look, revealing layers of different fabrics, colors, and designs," says Penny Rose. "The sheikh also has a headdress, and his boots are made from an old carpet."

Highly Visual Effects Complete the Picture: Filmmakers look to the pros for rewinds and extensions

"Just when you think that you've seen just about everything," says producer Jerry Bruckheimer, "we stand visual effects on their ear and do things that haven't been seen before. Hopefully, what you'll see on screen in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time will be something fresh, interesting and innovative."

Tom Wood and his extensive team of producers, managers, coordinators, data wranglers, and technicians were called upon to create nearly 1,200 visual-effects shots for the film. Some were long and involved-such as the time rewinds, the massive sandstorm in the climactic sequence at the Sandglass of the Gods, and the Lead Hassansin's vicious pit vipers-and some were minor little fixes at the edge of a frame.

Tom Wood enlisted all of the modern technologies and techniques at his command. Among the most important effects for Wood were the four time rewinds, caused when the jewel on the hilt of the dagger is pushed, releasing the Sands of Time. "We decided immediately that we couldn't just run the film backwards," explains Tom Wood. "We didn't want it to look like a VCR rewind. We had to develop an original and visually interesting approach. What we aimed for was a kind of slit-scan effect where everything would be warped by time and space.

"What we've done for the time rewind was designed by the visual-effects house Double Negative," Tom Wood continues. "They call it 'event capture.' We pre-visualised the sequence thoroughly with 'animatics' resembling animated storyboards. We then came onto the main unit set and shot the forward-running action, followed by four days of effects coverage, putting cameras in the positions that we wanted to capture the shot from.

"We have nine Arriflex 435 cameras shooting with identical lenses, up to 48 frames a second at a 45-degree shutter angle, which has caused a lot of challenges with relighting the set," Tom Wood continues. "That's to get as sharp an image as possible. We have a number of people from Double Negative who have laid out the cameras each time, surveyed into position. They have to be very precise. It takes about two hours to set up each array of cameras.

"We had to have our principal actors do 20 minutes of acting, go away for two hours, come back for another 20 minutes, and remember where they were. It's a challenge, trying to keep it fresh for each time that we see it."

The arduous filming of the time rewind sequences obviously challenged the actors' abilities of recall and concentration. "I'd never done visual-effects sequences before, and it's a really, really long process," admits Gemma Arterton. "But when you see it, it looks magical, adding a whole other dimension to the film."

Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time

Cast: Sir Ben Kingsley, Alfred Molina, Gemma Arterton, Jake GyllenhaalDirector: Mike Newell

Genre: Action, Adventure, Fantasy

Rated: PG

Running Time: 111 minutes

Synopsis: From the team that brought the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy to the big screen, Walt Disney Pictures and Jerry Bruckheimer Films present Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, an epic action-adventure set in the mystical lands of Persia. A rogue prince (Jake Gyllenhaal) reluctantly joins forces with a mysterious princess (Gemma Arterton) and together, they race against dark forces to safeguard an ancient dagger capable of releasing the Sands of Time-a gift from the gods that can reverse time and allow its possessor to rule the world.

Release Date: May 27th, 2010

Website: www.princeofpersiamovie.com.au

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview