Nick Hornby An Education Interview

HORNBY EDUCATES ON FRESH ADAPTATION

EXCLUSIVE Nick Hornby, An Education Interview by Paul Fischer in Toronto.Nick Hornby is one of the successful screenwriters and novelists of his generation. His often wry, British style have made him a household name, and some of his novels have been reinterpreted for American cinema, some more successfully than others. Born on April 17, 1957 in Maidenhead, England, Nick Hornby is the son of businessman Sir Derek Hornby.

When the younger Nick Hornby was 11 years old, his parents divorced and his father began taking him to watch the North London Premier League club Arsenal during their visits. He ultimately developed into a loyal, and somewhat irrational, fan of the team. Nick Hornby also became a dedicated reader, absorbing everything from comic books to Lorrie Moore. As an English Literature major at Cambridge University, he began composing stage plays, screenplays, and radio plays in his spare time. A professor then introduced Nick Hornby to novelist Anne Tyler's Dinner at a Homesick Restaurant, which inspired him to write prose. After graduating, Nick Hornby worked a series of jobs - he taught grade school, gave language classes, and served as host for Samsung executives visiting the U.K. -- before becoming a paid journalist. He composed a pop culture column for the Independent, and wrote about books and sports for publications like Esquire and the Sunday Times.

In 1992, he published his first book, Contemporary American Fiction, a collection of essays on American writers such as Ann Beattie, Raymond Carver, and Tobias Wolff. That same year, he released Fever Pitch, a memoir about being a devoted (and irrational) Arsenal fan since childhood. The work was a surprise hit, earning countless acclaim and selling out copies years into its release. Nick Hornby finished his first novel, High Fidelity, in 1995. The story of a record shop owner whose only lasting relationship is with pop music, High Fidelity earned accolades for both its compassion and its flippant refusal to compromise itself for political correctness.

Nick Hornby followed its success with the screen adaptation of Fever Pitch (1997), a four-star dramatic comedy starring Colin Firth as a schoolteacher struggling to sustain a romance against the backdrop of Arsenal's first championship season in 18 years. He also made a cameo appearance in the film. In 1998, Nick Hornby published About a Boy, a novel inspired in part by the children (especially the badly behaved adolescent girls) that he encountered as a teacher. The story follows Will, an immature single man, and Marcus, a struggling preadolescent, as they grow up together. His most favorably reviewed book to date, About a Boy, helped its author earn the E.M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1999. Unlike with Fever Pitch, Hornby did not pen the film adaptations of High Fidelity and About a Boy.

Co-written by its star John Cusack and helmed by legendary British director Stephen Frears, High Fidelity opened in 2000 to rave reviews and ended the year on many top ten lists. Despite having its setting transplanted from London to Chicago, the film still owed much of its success to its source material. About a Boy faired even better -- after buying the rights to the book for nearly three million dollars, Robert De Niro's Tribeca Films and Working Title commissioned What's Eating Gilbert Grape creator Peter Hedges to draft the screenplay.

The film went into production under the direction of brothers Chris and Paul Weitz with Hugh Grant and Nicholas Hoult in the lead roles and Nick Hornby as an executive producer. Released in 2002, critics hailed About a Boy as the best Nick Hornby adaptation to date.

While enjoying his big-screen success, Nick Hornby published How to Be Good, which earned him Britain's prestigious W.H. Smith Fiction Award in 2002. He also began working on several screenplays, including a collaboration with Academy Award-winning writer Emma Thompson. He continues to contribute to Time Out, the Sunday Times, the Times Literary Supplement, and is the pop music reviewer for the New Yorker. The parents of an autistic son, Nick Hornby and his ex-wife founded TreeHouse, a school for autistic children in London. In 2000, he edited a collection of short stories entitled Speaking With the Angel to raise funds for the school. The book includes writings by Colin Firth, Irvine Welsh, and Helen Fielding.

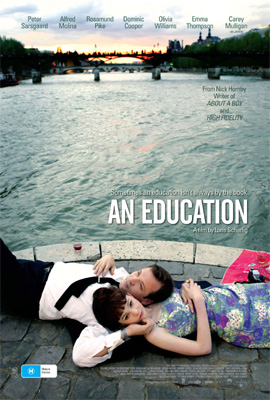

His latest screenplay, An Education, is based on Lynn Barber's memoir of growing up in London in the early 60s as a bright schoolgirl is torn between studying for a place at Oxford and the more exciting alternative offered to her by a charismatic older man.

Nick Hornby talked to Paul Fischer during the Toronto Film Festival.

QUESTION: The first comment that people make is that what's unusual about this is that you rarely adapt other people's work. Was it the historical aspect of this that drew you, or the characters?

NICK HORNBY: Well, I think the first thing that's kind of important to me when I'm thinking about anything, whether it's my own fiction, or something like this, is that it had a lot of tones to it. In that it had the potential for comedy, and great sadness. And there isn't that much stuff that comes along, actually, like that. Most things kind of lock into a groove and stay there. And - you know, the first - hopefully, the first half of the movie's funny, and then it becomes something else. But because my wife's an independent producer, and it's - stuff's in the air. You know, she's looking for stuff. And first of all, I read the piece and said, "You should do something with this." And then when they started to talk about writers, I felt very possessive of the material. And it was partly that, it was partly set in a very interesting time. You know, the '60s, back lot of the '60s.

QUESTION: A very conservative part of the '60s.

NICK HORNBY: Yes, exactly.

QUESTION: I mean, still sort of post-war.

NICK HORNBY: Yeah. No, it had much more in common - I mean, it's 1962, but it has much more in common with 1945 than 1963. And I didn't know - I didn't know those people, that kind of rather dangerous bohemian subculture that Lynn Barber had been knocking around in. And that - that was something fresh, for me.

QUESTION: Did you immerse yourself in the research? I mean, did you really have to do that? Or did you sketch out relationships first?

NICK HORNBY: Yeah. It was relationships and character first. I mean, one thing that weirdly became - you just become very insecure about what everyone's saying. It's like, "sleep with." "Do people say sleep with in 1962? What euphemisms did they use? What - how did they describe pregnancy" All that kind of thing. And so - linguistically, there was quite a lot to dissect. And - you know, I read a couple of books about the period, and - you know, when food rationing stopped, and how this would affect the mindsets of the people. I was a kid. I was five in 1962. So, in part, I was writing about my parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles, as well.

QUESTION: You're a screenwriter that has a great literary sense. How important are words to a screenwriter and to use language as the basis for a script?

NICK HORNBY: Well, I mean, I think that maybe my weakness as a screenwriter is that I - I tell stories through dialogue. And, of course, that doesn't make for the most visual film. So, you know, I think that in some ways - you know, because Lone is so good, and had such a visual sense for the film, that I think we were a pretty good combination in that way. She wanted to make the script, as it stood. But the moment I saw how her research worked, and the detail that she went into for the look, then I thought, "I'm with the right person." But - you know, there's a lot of dialogue in the film.

QUESTION: I mean, if this movie had been made or the story been told 20 years ago, there would certainly have been an outcry about the kind of almost Lolita-esque facet of this. Why do you think this is not as controversial as that particular story was, all those years ago?

NICK HORNBY: Well, I think that we've been quite careful. I - it's not a one-way manipulation. And I think that that comes across in that film. Jenny uses David to get access to a world that she wants to be a part of. I mean, you know, and she's 16 - it's not illegal. So, there's no legal issue. And also, David's quite gauche. Obviously there's a sleazy aspect to it, but he's a rather inept sleaze ball. There's a certain kind of charm to his ineptitude, I think.

QUESTION: What kind of writers have influenced you?

NICK HORNBY: I mean, obviously a lot of prose writers, but writers who write simply, and with song. So, my big inspirations when I started were Anne Tyler and Tobias Wolff, I think, in particular. In terms of screen, I love Preston Sturges. There's a couple of English guys, Galton and Simpson, who wrote a lot of radio and TV stuff that I grew up with, and I think are geniuses. So I have a lot of heroes. A lot of things go in, and come out in a different way.

QUESTION: What are your thoughts of the Americanizations of your work?

NICK HORNBY: Well, ithere's High Fidelity, and I don't have a problem with it. When High Fidelity came out and started being published in other countries, particularly America, nobody ever said, "Oh, this is what life is like in England." They always said, "My brother's like this. I'm like this. My boyfriend's like that." the locale really wasn't much of an issue, in terms of the responses to it. So I learned that even though I'd been writing about the area around my house, it was something that worked for people in Chicago and Berlin, and anywhere else. And - you know when someone comes to you and says, "Stephen Frears and John Cusack want to make this movie in Chicago," I don't think anyone's going to say, "You know what? I'd really rather they didn't." It was just - the sympathy for the work, and the talent involved, is always going to swing you around, I think.

QUESTION: And there was also that other soccer -

NICK HORNBY: Yeah. Well, that was - I mean, the sport did its work. No one really read the book, because they don't have any association with the sport. But Americans are huge sports fans, so I understood the logic of switching the sport.

QUESTION: What's happening with some of your other works, as - as movies? I mean, I think they're always talked about, some of your others. What's going on?

NICK HORNBY: Well, the two outstanding ones I guess are How to Be Good and A Long Way Down. How to Be Good was tantalizingly close to being made earlier this year, with a kind of dream team attached, which promptly then fell apart, and - so they're kind of trying to put it all back together again in a different guise. A Long Way Down got very stuck. Johnny Depp optioned it, but nothing was happening with it.

I've given it to Amanda and Finola now, who produced An Education.

QUESTION: So, is Depp going to do anything with it?

NICK HORNBY: I don't think so. I took it back from them.

QUESTION: Are you very disillusioned with the film industry at times?

NICK HORNBY: No. But it's an incredibly frustrating. I have a job in a different industry altogether, which is actually a very straightforward business, the book business. I mean, it's - you know, it's becoming increasingly tougher to sell books. But - you know, you write the book and it gets published. That's it. Whereas, as you know, film - every single script that gets written, it's a long shot that it ever reaches the cinema. And that's complicating and difficult. And as a screenwriter, for me, one of the biggest challenges with An Education was just keeping myself up to do another draft. You just think, "Why would you spend any more time on this, when no one's going to make it?" And of course, now, I think it's kind of the best job in the world. But it's a miracle when a small British film gets made. And when a small British film gets made with any kind of success.

QUESTION: As a novelist, do you feel the internet and mass communication has destroyed the love of reading?

NICK HORNBY: I don't think there's any sign of that yet. I think it might happen in generations to come. But people's relationships with books are actually fairly intense. And - I mean, it's still a very simple way - it's still the most pleasurable way of reading, I think. No one wants to read 80,000 words on a screen, which is why I think e-books are going to be slow to take off.

QUESTION: Why did you want to be a writer?

NICK HORNBY: Why?

QUESTION: Yeah. What was the beginning of that journey for you?

NICK HORNBY: I just knew I was.

QUESTION: At school?

NICK HORNBY: No. Well, actually, I think I probably knew I was from about the age of 18 or 19 onwards. It was always how I thought of myself. I didn't actually do much writing. But it's just that there was something in, that had to come out. And there isn't anything I could do about it. And I don't want to stop work. I'm incredibly pleased about work. And it still feels exactly the same way as it did. But there's an itch that needs scratching.

QUESTION: What's surprised you the most about your success as a writer both a novelist and as a screenwriter?

NICK HORNBY: It doesn't feel to me as though there've been any compromises involved, that I've always written exactly what I wanted to write. And yet, there has been a response of a scale that I hadn't anticipated. But they feel like personal stories, to me, that have found their way in the world. And I guess that's the big surprise.

QUESTION: Are you writing at the moment? What are you doing at the moment?

NICK HORNBY: Oh, got this for about three months. I've got a novel out this week. Next week, which is called Juliet Naked. So, I'm back here for a book tour in a couple of weeks.

QUESTION: You must love always talking about yourself, for months and months and months on end.

NICK HORNBY: [LAUGHTER] It really makes a difference with a movie, because I can talk about everybody else, which is fantastic.

QUESTION: On a book tour, what's the difference in promoting a book, from promoting a movie?

NICK HORNBY: I'm on my own. I mean, literally. There's no retinue of people.

QUESTION: Really? That's funny.

NICK HORNBY: Completely on your own, city to city. And - you know, the movie, I'm traveling with my wife, because she produced it. And we can share the success. I'm traveling with this fantastic team. And the film's doing well. So, it's really much more of a pleasure than talking about my book.

MORE

- Viggo Mortensen The Road

- 24 Cast Reunion

- Aaron Eckhardt No Reservations

- Aaron Eckhart The Dark Knight

- Adam McKay Step Brothers Interview

- Alan Alda Diminished Capacity Interview

- Alan Alda Diminished Capacity Interview

- Alex Dimitriades

- Al Pacino Oceans 13

- Alan Rickman Snow Cake

- Alan Rickman Sweeney Todd