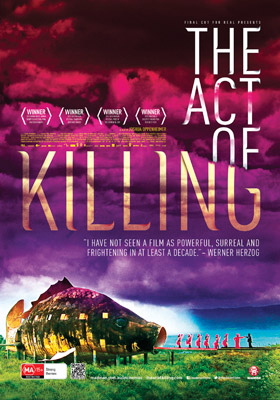

Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn and Signe Byrge Sørensen The Act Of Killing

Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn and Signe Byrge Sørensen The Act Of Killing

Cast: Haji Anif, Syamsul Arifin, Sakhyan Asmara

Director: Joshua Oppenheimer

Rated: MA

Running Time: 159 minutes

Synopsis: In this chilling and inventive documentary, executive produced by Werner Herzog (Grizzly Man) and Errol Morris (The Fog of War), the unrepentant former members of Indonesian death squads are challenged to re-enact some of their many murders in the style of the American movies they love.

In the 1960s Anwar Congo was a leader in Indonesia's pro-regime paramilitary group, Pancasila Youth who, along with his band of dedicated followers, was amongst those who participated in the murder and torture more than a million alleged Communists, ethnic Chinese and intellectuals. Proud of their deeds, which have still gone unpunished, Anwar and his pals are lauded as national heroes, and are delighted when the filmmakers ask them to re-enact these murders for their documentary – in any genre they desire. Initially Anwar and his friends enthusiastically take up the challenge using hired actors, making elaborate sets and costumes, but eventually as the movie violence is played out and reconstructed, Anwar's conscience begins to stir and feelings of remorse surface.

The Act Of Killing

Release Date: October 3rd, 2013

Statements

Director's Statement – Joshua Oppenheimer

Beginnings

In February 2004, I filmed a former death squad leader demonstrate how, in less than three months, he and his fellow killers slaughtered 10,500 alleged -communists' in a single clearing by a river in North Sumatra. When he was finished with his explanation, he asked my sound recordist to take some snapshots of us together by the riverbank. He smiled broadly, gave a thumbs up in one photo, a victory sign in the next.

These photographs betray not so much the physical situation of abuse, but rather forensic evidence of the imagination involved in persecution. And they were very much in my mind when, one year later, I met Anwar Congo and the other leaders of Indonesia's Pancasila Youth paramilitary movement.

Far away or close to home?

Far away or close to home? The differences between the situations I was filming in Indonesia and other situations of mass persecution may at first seem obvious. Unlike in Rwanda, South Africa or Germany, in Indonesia there have been no truth and reconciliation commissions, no trials, no memorials for victims. Instead, ever since committing their atrocities, the perpetrators and their protégés have run the country, insisting they be honoured as national heroes by a docile (and often terrified) public. But is this situation really so exceptional? At home (in the USA), the champions of torture, disappearance, and indefinite detention were in the highest positions of political power and, at the same time, busily tending to their legacy as the heroic saviours of western civilization. That such narratives would be believed (despite all evidence to the contrary) suggests a failure of our collective imagination, while simultaneously revealing the power of storytelling in shaping how we see. And that Anwar and his friends so admired American movies, American music, American clothing – all of this made the echoes more difficult to ignore, transforming what I was filming into a nightmarish allegory.

Filming with survivors

When I began developing The Act Of Killing in 2005, I had already been filming for three years with survivors of the 1965-66 massacres. I had lived for a year in a village of survivors in the plantation belt outside Medan. I had become very close to several of the families there. During that time, Christine Cynn and I collaborated with a fledgling plantation workers' union to make The Globalisation Tapes, and began production on a forthcoming film about a family of survivors that begins to confront (with tremendous dignity and patience) the killers who murdered their son. Our efforts to record the survivors' experiences – never before expressed publicly – took place in the shadow of their torturers, as well as the executioners who murdered their relatives – men who, like Anwar Congo, would boast about what they did.

Ironically, we faced the greatest danger when filming survivors. We'd encounter obstacle after obstacle. For instance, when we tried to film a scene in which former political prisoners rehearsed a Javanese ballad about their time in the concentration camps (describing how they provided forced labour for a British-owned plantation, and how every night some of their friends would be handed over to the death squads to be killed), we were interrupted by police seeking to arrest us. At other times, the management of London-Sumatra plantations interrupted the film's shooting, 'honouring" us by 'inviting" us to a meeting at plantation headquarters. Or the village mayor would arrive with a military escort to tell us we didn't have permission to film. Or an 'NGO" focused on 'rehabilitation for the victims of the 1965-66 killings" would turn up and declare that 'this is our turf - the villagers here have paid us to protect them." (When we later visited the NGO's office, we discovered that the head of the NGO was none other than the area's leading killer – and a friend of Anwar Congo's – and the NGO's staff seemed to be military intelligence officers.)

Not only did we feel unsafe filming the survivors, we worried for their safety. And the survivors couldn't answer the question of how the killings were perpetrated.

Boastful killers

But the killers were more than willing to help and, when we filmed them boastfully describing their crimes against humanity, we met no resistance whatsoever. All doors were open. Local police would offer to escort us to sites of mass killing, saluting or engaging the killers in jocular banter, depending on their relationship and the killer's rank. Military officers would even task soldiers with keeping curious onlookers at a distance, so that our sound recording wouldn't be disturbed.

This bizarre situation was my second starting point for making The Act Of Killing. And the question in mind was this: what does it mean to live in, and be governed by, a regime whose power rests on the performance of mass murder and its boastful public recounting, even as it intimidates survivors into silence. Again, there seemed to be a profound failure of the imagination.

Seizing the moment

In this, I saw an opportunity: if the perpetrators in North Sumatra were given the means to dramatize their memories of genocide in whatever ways they wished, they would probably seek to glorify it further, to transform it into a 'beautiful family movie" (as Anwar puts it) whose kaleidoscopic use of genres would reflect their multiple, conflicting emotions about their 'glorious past." I anticipated that the outcomes from this process would serve as an exposé, even to Indonesians themselves, of just how deep the impunity and lack of resolution in their country remains.

Moreover, Anwar and his friends had helped to build a regime that terrorized their victims into treating them as heroes, and I realized that the filmmaking process would answer many questions about the nature of such a regime – questions that may seem secondary to what they did, but in fact are inseparable from it. For instance, how do Anwar and his friends really think people see them? How do they want to be seen? How do they see themselves? How do they see their victims? How does the way they think they will be seen by others reveal what they imagine about the world they live in, the culture they have built?

Moreover, Anwar and his friends had helped to build a regime that terrorized their victims into treating them as heroes, and I realized that the filmmaking process would answer many questions about the nature of such a regime – questions that may seem secondary to what they did, but in fact are inseparable from it. For instance, how do Anwar and his friends really think people see them? How do they want to be seen? How do they see themselves? How do they see their victims? How does the way they think they will be seen by others reveal what they imagine about the world they live in, the culture they have built? The filmmaking method we used in The Act Of Killing was developed to answer these questions. It is best seen as an investigative technique, refined to help us understand not only what we see, but also how we see, and how we imagine. (The resulting film may best be described as a documentary of the imagination.) These are questions of critical importance to understanding the imaginative procedures by which human beings persecute each other, and how we then go on to build (and live in) societies founded on systemic and enduring violence.

Anwar's reactions

If my goal in initiating the project was to find answers to these questions, and if Anwar's conscious intent was to glorify his past actions, there is no way that he could not, in part, be disappointed by the final film. And yet, a crucial component of the filmmaking process involved screening the footage back to Anwar and his friends along the way. Inevitably, we screened the most painful scenes. They know what is in the film; indeed, they have profound debates about filmmaking inside the film, openly discussing the film's consequences. And seeing these scenes only made Anwar more interested in the work, which is how I gradually realized that he was on a parallel, more personal journey through the filmmaking process, one in which he sought to come to terms with the meaning of what he had done. In that sense, too, Anwar is the bravest and most honest character in The Act Of Killing. He may or may not -like' the result, but I have tried to honour his courage and his openness by presenting him as honestly, and with as much compassion, as I could, while still deferring to the unspeakable acts that he committed.

There is no easy resolution to The Act Of Killing. The murder of one million people is inevitably fraught with complexity and contradiction. In short, it leaves behind a terrible mess. All the more so when the killers have remained in power, when there has been no attempt at justice, and when the story has hitherto only been used to intimidate the survivors. Seeking to understand such a situation, intervening in it, documenting it – this, too, can only be equally tangled, unkempt.

The struggle continues

I have developed a filmmaking method with which I have tried to understand why extreme violence, that we hope would be unimaginable, is not only the exact opposite, but also routinely performed. I have tried to understand the moral vacuum that makes it possible for perpetrators of genocide to be celebrated on public television with cheers and smiles. Some viewers may desire a formal closure by the end of the film, a successful struggle for justice that results in changes in the balance of power, human rights tribunals, reparations and official apologies. One film alone cannot create these changes, but this desire has of course been our inspiration as well, as we attempt to shed light on one of the darkest chapters in both the local and global human story, and to express the real costs of blindness, expedience and an inability to control greed and the hunger for power in an increasingly unified world society. This is not, finally, a story only about Indonesia. It is a story about us all.

Co-Director's Statement – Christine Cynn

Humans love make believe. We love it so much we can make ourselves believe what is obviously false, even destructive. We love make believe so much that we find ourselves making belief for people who love us not at all.

Many of us also find ourselves acting in ways dissociated from what (we believe) we believe. In other words, we are rarely whom we imagine ourselves to be. This is as true of bankers and film directors as it is true of death squad leaders. The Act Of Killing hopefully reveals more than another terrifying example of human brutality and injustice. My hope was that the film might lead us to question the role of our imaginations in perpetuating a delusional social cycle, driven by struggles for power, and spiked with performances of terror and mass murder that are invariably followed by false historical narratives.

I do not consider myself an optimist, but I am convinced that not all -make believe' need be delusional. Human imagination is the key to empathy, which leads us to acts of compassion. Imagination is also the foundation of curiosity, which leads us to acts of discovery. This, in turn, changes what is possible. Human imagination might also lead us to break the cycles of self-deception and their devastating consequences if, and only if, we find the humility to admit responsibility for them.

Co-Director's Statement – Anonymous

I was one of thousands of Indonesian students who stood face to face with riot police in 1998, urging the New Order military dictatorship to go. I was not one of the student leaders who delivered heated speeches to the crowd; I was only a supporter, who felt that this moment might be historically important.

After more than three decades in power, General Suharto had finally stepped down. Since then, there have been some changes. The constitution has been amended four times. The press has become relatively freer. The President and Governors are elected by the people. There are no limitations on the numbers of political parties, although it remains illegal for any of them to declare a Marxist affiliation.

However, working with grassroots communities, trying to create a fairer distribution of natural resources, for example, I repeatedly hit a dead end. Everywhere, corruption is still rampant. Munir, a human rights activist, was murdered by leading officials in the Indonesian intelligence services while on a flight to Holland, where he was to pursue a graduate degree -- and there has been no effort to prosecute those responsible. Violence is still often used as the primary language of politics. The buying of votes has transformed -democracy' into, at best, a formal, almost stage-set procedure... In other words, nothing has really changed since the day General Suharto seized power -- even now, 14 years after he gave it up. The façade of Indonesian politics might have altered since the 1998 political reforms but, behind it, the old machinery still works in exactly the same way.

In 2004, I met Joshua and helped him begin his filmic exploration of the 1965-66 genocide in North Sumatra. Initially, I came to help for a month, not realizing that it would mark the beginning of an eight year collaboration. Making this film has become a personal journey for me, in seeking to discover why this social and political stasis remains.

Through the imaginations and recollections of the mass murderers featured - men who supported, even created this corrupt structure – I understand, with particular clarity, how one of the devices of the old regime is still working so efficiently. It is the -projector' that keeps playing, on an endless loop, a fiction film inside every Indonesian's head. People like Anwar and his friends are the projectionists, showing a subtle but unavoidable form of propaganda, which creates the kind of fantasy through which Indonesians may live their lives and make sense of the world around them; a fantasy that makes them desensitized to the violence and impunity that define our society. This is the true legacy of the dictatorship: the erasure of our ability to imagine anything other. I worked with Joshua to make The Act Of Killing in order to help myself, other Indonesians, and human beings living in similar societies around the world, to understand the importance of questioning what we see, and how we imagine. How else are we to envision our world in a different way?

Through the imaginations and recollections of the mass murderers featured - men who supported, even created this corrupt structure – I understand, with particular clarity, how one of the devices of the old regime is still working so efficiently. It is the -projector' that keeps playing, on an endless loop, a fiction film inside every Indonesian's head. People like Anwar and his friends are the projectionists, showing a subtle but unavoidable form of propaganda, which creates the kind of fantasy through which Indonesians may live their lives and make sense of the world around them; a fantasy that makes them desensitized to the violence and impunity that define our society. This is the true legacy of the dictatorship: the erasure of our ability to imagine anything other. I worked with Joshua to make The Act Of Killing in order to help myself, other Indonesians, and human beings living in similar societies around the world, to understand the importance of questioning what we see, and how we imagine. How else are we to envision our world in a different way? I must remain anonymous, for now, because the political conditions in Indonesia make it too dangerous for me to do otherwise.

Producer's Statement – Signe Byrge Sørensen

Ever since I was young I have wondered about the Nazi extermination of the Jews, as well as other genocides. Why do they happen? What makes some people turn on other people in such a terrible way? Why do neighbours start killing neighbours? And why do others let this happen? When studying these issues more closely, I discovered that the stories people tell about each other play an enormous role in the process of genocide. If we identify a group of people, define them as terrible, evil, and very strong, somehow it becomes easier to kill them. After all, the killers can claim it was all in self-defence, and that the victims were the -bad guys'.

And if, at the same time, the people in charge have hierarchies, resources, and henchmen in place, then the process becomes terribly easy, and sometimes extremely fast. If, on the other hand, we have critical voices who ask difficult questions about the legitimacy of what is happening, then the killing process may be interrupted, and the outcome less inevitable – and this interruption may at least give everyone some time to think. In the best case, it may even stop the process, before it is too late.

Joshua Oppenheimer is someone who asks difficult questions. And in this film he questions the people we fear the most: the killers. However, he does not only focus on the lower level perpetrators, and he is not satisfied by easy psychological explanations. He persists until he can show the whole hierarchy involved, and he reveals layer by layer how storytelling, killing, politics and economics are closely related. When I met Joshua and heard about his project, I met a director who was not out simply to make a film (as hard as that is), but also to make a fundamental investigation into the human, social, and political conditions that make genocides possible. I am proud to be on this journey with him.

The Act Of Killing

Release Date: October 3rd, 2013

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview