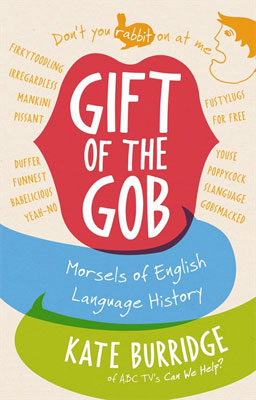

Gift of the Gob Morsels of English Language History

Title: Gift of the Gob Morsels of English Language HistoryURL: gift-of-the-gob-morsels-of-english-language-history.htmDescription: Why can we fall in love but not in hate? Why not one house and two hice? Gift of the Gob examines our language and the everlasting tug-of-love that exists between 'proper' English and its wayward relation slang. Keywords: Kate Burridge, Gift of the Gob Morsels of English Language History, English Language History, Gift of the GobJ:\femail-img\giftofthegob.jpgJ:\femail-img\giftofthegob_s.jpg

Gift of the Gob Morsels of English Language History

Why can we fall in love but not in hate?

What do codswallop and poppycock share?

Why not one house and two hice?

How come we scream blue murder, sing the blues and turn the air blue?

From Professor of Linguistics and ABC TV and ABC Radio regular Kate Burridge, comes Gift of the Gob, a witty and eclectic look at the quirks of the English language.

Join Kate on a fascinating journey through English language history, as she untangles words and their meanings, and unearths the centuries of spectacular changes that have transformed the very core of our language.

Gift of the Gob examines our language and the everlasting tug-of-love that exists between 'proper' English and its wayward relation slang. Professor Burridge investigates the place where all that is 'wrong', 'bad' or 'sloppy' slips into everyday use, before becoming 'proper' in its turn!

Based on segments from ABC Radio's Soundbank and ABC TV's Can We Help?, Gift of the Gob explores the poetic ingenuity of common language and celebrates linguistic shenanigans through the ages!

Kate Burridge is a prominent Australian linguist who is currently Professor of Linguistics in the School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics at Monash University. She is a regular presenter of language segments on ABC Radio and on ABC TV's Can We Help?.

Gift of the Gob Morsels of English Language History

ABC Books

Author: Kate Burridge

ISBN: 9780733324048

Price: $27.99

Interview with Kate Burridge

Why did you decide to write Gift of the Gob: Morsels of English Language History?

Kate Burridge: I am fascinated by language, particularly language change, and much of what I investigate in this book is the vernacular. This is why I wanted the title Gift of the Gob rather than its more respectable twin, the modern-day phrase Gift of the Gab. I felt the slightly shabby expression gob 'mouth' provided just the right image. Gift of the Gob should bring to mind 'nimble-tongued eloquence' - mouth-filling morsels of English language history, especially the ones that tell of the tug-of-love between the vernacular and standard usage.

I should emphasise that Gift of the Gob was also inspired by the general public - published letters to editors and also personal letters, emails and general feedback that I've received over many years of public lectures (for schools, festivals, charities and a range of societies and institutions). They are also the result of more than sixteen years involvement with the ABC, preparing and presenting weekly programs on language for radio and, more recently, for television. During this time, I've been lucky enough to be involved in a number of talkback radio programs and have also been given the opportunity to write regular pieces for ABC radio's Soundbank. This book features a number of these. The chance to present a weekly language spot on the ABCTV show Can We Help) has provided me with many more tidbits - far more than I could squeeze into this book.

There have been many wonderful questions over the years and they've taken me down linguistic paths I would never have envisaged. Frequently, of course, these questions involve complaints, often quite passionate. But people's concerns are what regularly alert me to something interesting happening in the language - a new discourse particle, a meaning shift, a grammatical change perhaps. As I've said on many occasions, the clues to where a language like English is heading often lurk in the linguistic constructions that many regard as wrong, bad or sloppy. Linguistic pinpricks - such as between you and I, mischievous, gotten, penultimate ('greatest'), yeah-no, to verse and so on - provide me with a constant source of ideas for exploring linguistic change.

How has the way we speak and write changed over time?

Kate Burridge: This is a big question. Let me set the scene with a quotation from the great English poet Geoffrey Chaucer:

Ye knowe ek that in forme of speche is chaunge

Withinne a thousand yeer, and wordes tho

That hadden pris, now wonder nyce and straunge

Us thinketh hem, and yet thei spake hem so,

And spedde as wel in love as men now do;

You know that even forms of speech can change

Within a thousand years, and words then

That meant something, now seem very comical and strange

To us, and yet lovers speaking them so

Prospered as well in love just as we do now.

[Troilus and Criseyde, c. 1385]

Geoffrey Chaucer is emphasising here the instability of the very medium in which he is working, the English language. As he says, in 'forme of speche is chaunge'. He talks about language changing over a thousand year period. In fact, just over 600 years separate us from the time of Chaucer and yet his language is to us already 'wondrous strange' (to use his own words). A thousand years ago, it was stranger still - indeed, not even recognisably English. Compare the first line of a hangover cure from the 10th century. A few hundred years before the time of Chaucer and the language is totally incomprehensible:

Wiþ þon þe mon hine fordrince . Genim swines lungenne gebræd 7 on neaht nerstig genim fif snæda simle

"In the event a man over-drinks himself. Take a pig's lung, roast it, and at night-fasting take five slices always"

Clearly, English has changed enormously (and hopefully hangover cures, too!). The further we go back in time, the stranger the language appears to us.

Clues to where the language is heading are everywhere and the key is variation, the infinite variation in everyday speech. What many people think of as slipshod pronunciations, mistakes in grammar, coinages, new-fangled meanings and so on - these are the basis for real change. The majority of them will drop by the wayside, it's true, and some will remain variation. But there will also be some that catch on, be used more and more and will eventually form part of the repertoire of Standard English in the future. To draw on a garden metaphor - today's weeds may well become tomorrow's cherished garden varieties.

Language cannot be fixed. All aspects of the system - sounds, words, grammar - are constantly on the move. Why this change happens is the most complex and, for me, the most fascinating question of all. It involves, as you would imagine, a complex interaction of different social, psychological, linguistic and external (e.g. contact with other languages) factors. Even fashion is involved - people want to change their language (especially vocabulary), like they want to change the hemlines on the trousers and dresses they wear. The history of a language like English chronicles the enduring tussle between speakers' desire for new, exciting ways of saying things and the tendency for words and structures to become mundane and routine.

Do you think the modern changes to the way we use the English language are positive or negative?

Kate Burridge: As I've just emphasised, English has been changing throughout its lifetime and it's still changing today. For most of us, these changes are fine as long as they're well and truly in the past. Paradoxically, we can be curious about word origins and the stories behind the structures we find in our language, but we experience a queasy distaste for any change that might be happening right under our noses. There are even language critics who are convinced that English is dying, or if not dying at least being progressively crippled through long years of mistreatment.

For example, many people in Australia worry about their language and its relationship with its powerful relative, American English. In particular they express concern for the 'Americanisation' of the language - it's a hot topic here in Australia. There are identifiable American influences on teenage slang and, more generally, on teenage culture, but the impact elsewhere on the language is minimal. Nonetheless, reactions from older and also younger folk are typically hostile. Newspaper headlines, such as 'Facing an American Invasion', go on to 'condemn this insidious, but apparently virile, infection from the USA'. In letters to the editor and talkback calls on the radio, speakers rail against 'ugly Americanisms' - many of which, in fact, are not Americanisms at all. Nothing seems to calm these critics of American English, even pointing out (as I have done on many occasions) that some of our beloved Australianisms came originally from America, as in bush "sparsely settled areas as distinct from towns" and squatter "one who settles upon land without legal title". The influx of Americans to the goldfields from the 1850s supplied several of the current favourites in the Australian lexicon (see Ramson 1966).

There is a special human kind of doublethink involved here. The fact that Shakespeare might have misinterpreted the word groveling and backformed a new verb to grovel is interesting; the fact that younger Australians have done the same with versus and created a new verb to verse "compete against" (as in Team A is versing Team B) is calamitous. If dictionaries makers and handbook writers do acknowledge current usage and include entries like to unfriend and nomophobia, there are howls about declining educational standards; yet dictionaries that fail to update cease to be used (as in the case of the Funk and Wagnalls, cf. Stockwell and Minkova 2001: 191f). Sticky wickets, cleft sticks, rocks and hard places always come to mind when I think of the plight of the dictionary-maker.

Certainly, vocabulary more than any other aspect is prone to change and dictionary makes are constantly having to redraw the admission and exclusion boundary for marginal vocabulary items. Yeah-no is a new discourse marker in Australian English. So when will it appear in our dictionaries? For many of us a couple means "a few". When will the Macquarie Dictionary acknowledge this meaning? It is almost impossible for printed dictionaries to keep up with the protean nature of vocabulary. Words and expressions come and go. They are constantly updating their appearance, their nature, their behaviour - and they have to. How else could they convey the wealth of concepts that we want to put into words? Meanings, in particular, are prone to change. More than other aspects of language, vocabulary is linked to the life and culture of speakers and this can take them on some extraordinary semantic journeys. At any one time, words can hold a multiple of different meanings. Together with all the associated baggage that arises from our personalities and prejudices, these slip and slide around over time as language evolves and adapts.

I want to emphasise, with fanfare and with trumpet blast, that flux and variance are natural and inevitable features of any language. The only languages that don't change are dead ones! With over 350 million first language speakers and even more second language speakers, English is well and truly alive - the future has never looked so good.

Do you believe that the English language is one of the hardest languages to learn?

Kate Burridge: If people are interested in this question, then I thoroughly recommend Peter Trudgill and Laurie book Myths about Language (New York: Penguin). It has a wonderful chapter that addresses exactly this question.

As this chapter emphasises, it is in fact impossible to say which is the hardest language to learn. There are basically two reasons for this. One, it depends where you start from. If English is your mother tongue, then it's going to be far harder to learn a language that isn't closely related - or indeed linguistically related at all. An English speaker would find Irish or Welsh difficult, more difficult than Dutch and German. These languages are all our relatives, to be sure, but Dutch and German are near relatives, being in the same Germanic family as English. Even harder would be to learn languages from a completely different language family, say one of the Australian Aboriginal languages, or a Dravidian language like Tamil, or an Amerindian language like Nootka and Navaho. The sounds and grammar could be very different and the vocab unfamiliar, not just in form but also in content. And as anyone who has learnt a language knows, vocabulary is probably one of the most challenging aspects of foreign language learning.

But what also makes it hard to determine the relative difficulty of a language is that we are dealing with complexity at different levels. Take sounds. English has around 44 distinctive sounds. Hawaiian has 13 (this is one of the simplest sound systems). Compare this to a language spoken in Southern Botswana (a Hottentot language) - one that is reputed to have 156 different sounds, 78 of which are clicks. From the point of view of sounds this language would be a difficult one!

Then there is complexity at the grammatical level. One example might be the shape of words. When it comes to grammatical bits and pieces English is impoverished - compared to its linguistic relatives, it's very much the poor relation. An English noun like duck can have two forms only (duck/ducks) and verbs come in fours (quack/s/ed/ing). Modern Italian and Spanish verbs have about 50 different forms; Classical Greek 350. There are some languages like Greenlandic that are far more complicated than this. It is all mind-boggling complexity for an English speaker! In absolute terms, a language that is like English (which has little of this sort of complexity) is probably easier than a language like Greenlandic - English might use more words to capture something that could be expressed in one word in Greenlandic, but complexity of grammar à la the Greenlandic system can make life very difficult for language learners.

There are also languages that are complex from the point of view of rules of politeness and indirect speech styles. A simple example is French and German. These languages have a distinction between a formal an informal 'you' pronoun. This means that French and German speakers must pay special attention to questions of status and solidarity when they address someone. Every time they need to say 'you' they must make sometimes excruciatingly difficult decisions as to which pronoun to use. So French and German speakers would have to be much more attuned to social details to do with age, sex, status, degree of familiarity of people they are speaking to, much more than, say, English speakers who don't make this tricky distinction. In some languages such politeness features are far more complex than this - in Japanese they saturate every level of the language.

In short it is impossible to say what language is the hardest to learn because there is no straightforward measure of simplicity. Typically what you find is complexity in one area of the language and simplicity in another.

How has the introduction of slang and jargon changed the way everyday Australians communicate?

Kate Burridge: Before I answer this question, I should probably say something about the nature of slang and jargon: What exactly are they and how do they relate to each other?

Begin with slanguage. It's true, people often sling off at slang. As someone early last century wrote, "slang is to a people's language what an epidemic disease is to their bodily constitution". Many connect it with swearing too, but this is in fact mistaken. Slang can be obscene, certainly, but it's not necessarily connected to taboo in the same way that swearing is. And as Lars Andersson and Peter Trudgill point out in their book on bad language, many people also wrongly identify slang with adolescent speech - as something we eventually grow out of. Certainly, teenagers use slang, but then so do adults. There are also those who view slang as a linguistic feature peculiar to modern times. This most certainly is not the case. Admittedly it's hard to make stylistic judgements on slang from the past, but slang has always been with us.

So what are the features that identify a piece of language as slang? For a start, it's obviously informal, usually spoken not written and it involves mainly vocabulary. One striking feature is its playfulness. Metaphor, irony and sound association are important forces behind new slang expressions. Take colloquial terms for drunkenness like sloshed, soused, smashed, sozzled, soaked, stewed or even steamed. The imagery here you'll notice is strongly underpinned by sound association. All these words begin with "s". Another characteristic of slang is reduction of form. Teenagers from all around the English-speaking world have been using terms like rents (< parents), rad (< radical), and dis (< disrespect). But probably the most important feature of slang is that it's unstable. I can imagine that many younger speakers will find these expressions rents, rad and dis well and truly passé by now! The whole point of slang is to startle, amuse, shock. It has to be short-lived. A study done of university slang over a 15 year period showed that only 10% of the expressions survived. If a slang expression does survive, then it's usually no longer slang. It's hard to imagine that such dull little words as pants and mob were once controversial slangy abbreviations (of pantaloons and mobile vulgus). Finally, slang serves the dual purpose of solidarity and secrecy. It indicates membership within a particular group, as well as social distance from the mainstream. At the same time, it also prevents bystanders and eavesdroppers from understanding what's being said. This was in fact the original motivation of slang. When the word first appeared it referred specifically to the secret idiom of the British underworld.

So how does slang then differ from jargon? Like slang, poor old jargon is much maligned. Many people use the term pejoratively. Jargon is what turns "a toothbrush" into "a home plaque removal implement" - it's intellectual hocus pocus. In 1991 when Keith Allan and I were investigating jargon we came across the following glorious example from sociology - "the objective self-identity as the behavioural and evaluative expectations which the person anticipates others having about himself". Why doesn't the writer simply use the word self-image, we wondered? (Of course I could have taken an equally wonderful dollop of verbal flummery from my own discipline of Linguistics - but it's always more fun to tilt at the jargon of others!) It's not surprising that jargon is frequently used contemptuously to describe language full of unfamiliar terms; in other words, "gibberish".

But equally you could describe jargon as simply the language peculiar to a particular group of persons such as a profession or a trade. To be fair, in the context of the article in the British Journal of Sociology the gem of jargon I mentioned above doesn't look so bad and presumably the writer didn't simply use it to augment his own objective self-identity as the behavioural and evaluative expectations which he anticipates others having about himself! Whether or not you apply the term jargon contemptuously will of course depend on whether or not you're a member of the group in question.

So jargon and slang do overlap. Both identify activities, events, and objects that have become routine for those involved. Both have an important function in creating rapport in the work or play environment. The difference is slang is more colloquial and has a much faster turnover rate. Also slang can usually be replaced by more standard expressions. Hence the dictionary description "colourful, alternative vocabulary". You could describe someone as pickled, pissed or plastered or you could simply say they're drunk. It's true - a lot of jargon is very replaceable, too. Legal language, for instance, is characterized by curiosities like thereupon, hereinafter and herebefore which could quite easily be dispensed with, or at least replaced with modern-day equivalents. Like slang, jargon items such as these are a matter of style. They are built into the linguistic routine of this particular jargon and are now part and parcel of the rituals of the legal profession. But then again, many jargon expressions don't have viable alternatives in ordinary language - the lawyer's plaintiff, the art historian's skeuomorphy, the linguist's morpheme, even the cricketer's man at deep fine leg. These refer to activities peculiar to each group and they fill a need. And in this respect, jargon can be very different from slang.

Now, to answer the original question - both slang and jargon have always been generous contributors to the English lexicon. This is something they both share. Ordinary language is constantly being enriched by the influx of vernacular and specialist expressions that eventually end up in mainstream dictionaries. We should all be more appreciative, for it's precisely sublanguages like these that maintain the fecundity of our Aussie lingo!

Do you think the introduction of text messaging is to blame for the world speaking in acronyms such as 'OMG', 'BFF' and 'LOL'?

Kate Burridge: English speakers have always loved abbreviations and acronyms. The reasons are probably obvious. Their primary function (whether the context is text messaging or elsewhere) is precision and economy. How tedious it would be if every time we referred to the ABC we had to use the full expansion Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Small wonder BSE has come to replace bovine spongiform encephalopathy, the technical name for "mad cow disease". But there's a second function too and that is to promote in-group solidarity - to exclude those who don't understand as outsiders. Acronyms and abbreviations act as a kind of masonic glue to stick members of the same profession together. If you can talk fluently of 'OMG','BFF' and 'LOL', then to the computer literate you're immediately identifiable as a fellow member of the club. But if you don't know that OMG is "Oh my God", BFF "best friends forever", LOL "laugh out loud", then you're obviously a dangerous outsider. So while these words facilitate communication on the one hand, they also erect pretty big communication barriers on the other. For those not in the know, acronyms are unintelligible gibberish. And if you find yourself in this position, you'll be relieved to know there is a club for you: the "Association for the Abolition of Asinine Abbreviations and Absurd Acronyms", known of course as the AAAAAA or triple A, triple A!

Texting and other examples of e-communication will clearly speed up the rate of language change. Many of these shortened expressions have already escaped the Internet and have made it into written language elsewhere. But the impact of the electronic revolution is much more significant than a few new lexical items. The writing process (and the conscious self-censorship that accompanies it) generally has a kind of straitjacketing effect that safeguards the language to some extent from what Samuel Johnson described in 1755 as the 'boundless chaos of a living speech' - in other words, the flux and variance that is the reality of language. The powerful authority of writing has had the effect of retarding, perhaps even reversing, the normal processes of change. But this influence is waning. It took hundreds of years for will to evolve into a new marker of future time. The changes that are transforming going to into the future auxiliary gonna are much faster. We are now seeing see the 'boundless chaos of a living speech' represented there in written form. There are even virtual speech communities too where face-to-face communication happens through electronic means. This must have a long-term and momentous effect on the language.

But back to acronyms! It's true; we seem to be swimming in a sea of acronyms these days. But some people might be relieved to know the majority remain peripheral to the language. They serve either as proper names like Qantas (Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services) or are specific to certain occupations like SOC (Staff Observation Checks), part of hamburgery lexicon of McSpeak. It's true there have been some escapes like those from text messaging, but the majority are never likely to become a part of our general lexicon.

MORE