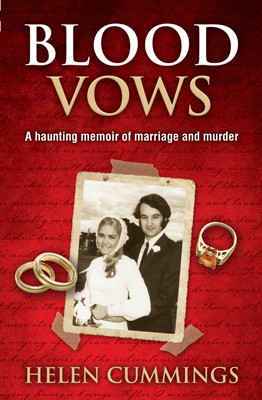

Blood Vows

Blood Vows

In 1970, a pretty young woman called Helen Cummings married a handsome doctor called Stuart Wynter. But instead of being a marriage made in heaven, it was the beginning of a hellish existence of spiraling abuse that ended six years later when she escaped with her two young children. Except it wasn't the end at all because Dr. Wynter remarried - and this woman and her child weren't able to escape, and Helen wasn't able to help.

In this brave memoir, Helen Cummings relates an idyllic childhood growing up in 1960s Newcastle and looks back on a marriage that nearly killed her and her children. Nowadays Helen is 'the mother of a famous daughter and the daughter of a famous mother', but she has also had to come to terms with her painful past.

Helen Cummings worked with the Family Court between 1985 and 2010, first on the counter in the registry, later as an associate to a federal magistrate. Helen was born in the northern New South Wales town of Newcastle, where she lives today. She has two children from her first marriage, and one from her second.

Blood Vows

Five Mile Press

Author: Helen Cummings

ISBN: 9781742485881

Price: $32.95

Interview with Helen Cummings

Question: Why do you believe it was important to write Blood Vows?

Helen Cummings: I do believe the publication of my story "Blood Vows" is important and timely.

Very little is known or researched intofamilicide which is the killing of one's whole family. It is too difficult and painful for those who are left to talk or write about. It took 20 years before I considered documenting my story and another 4 years to write it for publication. Raken and Binatia the two people who were murdereddid not live to tell their story so have no voice. They have no family here and their island nation of Kiribati is being submerged due to climate change. My book is dedicated to them and my children who survived.

Sarah and Brendan, my two adult children knew nothing about their father in our happier times. There is a love story in our early courtship. I did not want their father to become the elephant in the room or skeleton in the closet. The bad memories were tossed out with the good onesafter the murders. I did not want anyone else to tell or rewrite our history. When something cannot be talked about the imagination takes over. I take responsibility for any consequences in putting our private lives out to a wider audience.

The most important reason though is the legislation with regard to Family Law and the provisions that put Australia's most vulnerable, our children in harm's way if unsafe orders are made.

Question: Was it hard for you to write Blood Vows and relive the times you write about?

Helen Cummings: Writing the story and reliving the times was not easy. My office is part of my bedroom and many days I dived from my chair to my bed, emotionally spent.

It was not as if, I woke up one day and decided that my story needed to be told. It was a long slow process but at some point there was no going back. Many of the memories were tucked away but not out of reach. Few people other than family and the closest of friends knew what we had been through and after the murders it became even more unspeakable. There are long periods that I cannot recall at all. I suspect that during those times when my mind was on high alert and in fear for our lives that the mundane day to day stuff was erased. I have not recorded other people's unpleasant memories of our time because they are not my memories but I have no doubt they occurred.

Question: What research into the Family Law Act, did you do before writing Blood Vows?

Helen Cummings: I worked in the Family Law system for 25 years and followed the changes to the Act closely. The changes never succeeded in making bad parents good.As a retiring Family Court Judge said "You cannot legislate for goodwill".

The 2006 legislation is unmanageably large and complicated. Judicial officers are required to go through a complex calculation process just to make orders about children living or spending time with an abusive parent. It is like a mathematical calculation and government intention than children's safety.

Applicants caught in the nightmare of domestic violence are required to file a form called "Notice of Risk of Child Abuse or Family Violence". Very few have ever been filed because of the risk of not being able to prove the abuse and violence.In which case, they could be ordered to pay the costs of the other party. Evidence is often impossible in the privacy of one's home.

The legislation has a hierarchy that puts a child's need for a meaningful relationship with both parents before a child's need for nurturing and love and protection against abuse.

I often wondered if the people who framed the laws ever had a small child in fear looking to them for safety - to make everything better.

There are many other provisions that need amending and I have addressed them all in the book.

Question: Can you talk about the effect Blood Vows has had on your family?

Helen Cummings: There was never a guarantee of unforeseen pain when I allowed the publication of my story. I continually questioned my motives throughout the writing to be clear in my own mind but in the end I don't know and have to take responsibility for any consequences. My two adult children who are part of the story gave me permission to write the story for a wider audience. There is an ongoing legacy for Sarah and Brendan and the issues go much deeper than removing the elephant in the room or the skeletons in the closet.

The younger generation in the Cummings and Wynter families who are now all grown knew very little about what happened all those years ago and curiosity is powerful. It is better to know the true story and understand the reasons for writing it. I was mindful of the people of Gloucester and Heathcote who were his friends and patients when writing.

I can only hope and pray that after you read my story you will understand better, my reasons for writing it.

Interview by Brooke Hunter

MORE