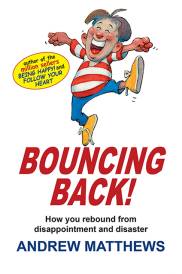

Alex Gibney The Armstrong Lie

Alex Gibney The Armstrong Lie

Cast: Lance Armstrong, Reed Albergotti, Betsy Andreu

Director: Alex Gibney

Genre:Biography, Documentary, Sports

Rated: M

Running Time: 123 minutes

Synopsis: Lance Armstrong was considered one of the greatest sports figures of all time and put competitive cycling into the global spotlight, by beating cancer and winning the Tour de France seven times. That success earned him an immense fortune and worldwide fame. His was also one of the most influential and inspiring sports stories of recent memory and became a pop culture phenomenon, thanks to his Livestrong initiative. Beginning in 2009, Academy Award winning documentarian Alex Gibney followed Armstrong for four years chronicling his return to cycling after retirement, as he tried to win his eighth title.

Unexpectedly, Gibney was also there in 2012 when Armstrong admitted to doping, following a federal criminal investigation, public accusations of doping by his ex-teammates, and an investigation by the US Anti-Doping Agency, that led USADA's CEO, Travis Tygart, to conclude that Armstrong's team had run 'the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that sport has ever seen.

The Armstrong Lie

Release Date: March 13th, 2014

About The Production

'I didn't live a lot of lies. But I lived one big one. You know, it's different I guess. Maybe it's not. But yeah, it's… And what I said in there with just how this story is all over the place and there are these two… you know, these just complete opposite narratives. You know… The only person that can actually start to let people understand what the true narrative is, is me. And you should know that better than anybody else to the get into the… the real nature and the real detail of the story. Because we haven't heard it yet is the truth." - Lance Armstrong; January 14, 2013

In The Armstrong Lie, acclaimed documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney turns his camera on one of the most riveting stories in the history of sports, the impossible rise and spectacular fall from grace of former cycling champion and inspirational hero, Lance Armstrong.

In The Armstrong Lie, acclaimed documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney turns his camera on one of the most riveting stories in the history of sports, the impossible rise and spectacular fall from grace of former cycling champion and inspirational hero, Lance Armstrong.

Lance Armstrong went on to become one of the most remarkable figures in sports history, winning his first Tour de France (cycling's greatest race and one of the world's most grueling athletic competitions) the following year, in 1999. From there his legend took flight.

Lance Armstrong published his bestselling memoir: 'It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life," in 2000. Between 1999 and 2005 he would go on to win the Tour de France a record seven times in a row. Though dogged (as were other cyclists) by persistent rumors of using illicit performance enhancing drugs, Armstrong, during this phase of his career, was consistently certified as drug-free by cycling's governing bodies and continued to race – and win.

With his remarkable tale of personal triumph and racing victories, Lance Armstrong brought a never before seen prominence to the sport itself and raised vast sums for charity (with millions alone though the sale of yellow -Livestrong' bracelets). Basking in the glow of international celebrity, he also remained an inspiration to cancer patients and survivors, symbolising the potential of the human spirit. Through sponsorships, product licensing and endorsements, he had also amassed a vast personal fortune.

In the spring of 2005, Lance Armstrong, approaching his 34th birthday, announced his retirement from professional cycling. It would follow his seventh back-to-back Tour de France victory later that summer (completing the event, notably, at the fastest pace in the race's history), citing his desire to spend more time with his children. '"My children are my biggest supporters," said Lance Armstrong at the time. 'But at the same time, they are the ones who told me it's time to come home."

By September 2008, however, Lance Armstrong announced that he would return to cycling - with no less a goal than competing in the 2009 Tour de France. With the promise of unfettered access and a remarkable story in the making, acclaimed filmmaker, Alex Gibney, signed up to go along for the ride.

A veteran documentarian, Alex Gibney is the filmmaker behind the 2008 Oscar®-winning documentary Taxi to the Dark Side and the 2006 Oscar®-nominated Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Heralded by Esquire magazine – '[Alex Gibney]…is becoming the most important documentarian of our time" – his remarkable list of credits includes: We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks; Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer; Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson and the Jack Abramoff documentary, Casino Jack and the United States of Money.

Given unprecedented access to Lance Armstrong and the world of professional cycling, Alex Gibney turned his cameras on the sports legend, his teammates and trainers (including the controversial Italian physician and coach, Michele Ferrari) in 2008-2009, embarking on what he believed would prove the ultimate comeback story under the working title: 'The Road Back." Joined by his production team, he followed Armstrong's progress for a little over a year (joining Armstrong for the 2009 Tour de France and again for the 2010 Tour) and all but completed his edit in 2011. But what Gibney, along with most observers, couldn't anticipate were the events which would unfold – a US Federal criminal inquiry (subsequently dropped without charges), and more crucially, an investigation by the regulatory body, the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), which would ultimately end Armstrong's career.

Alex Gibney's project was suspended as the story of the doping scandal supplanted that of Armstrong's comeback in the public eye. It was re-opened as Lance Armstrong stepped forward to make his public confession in 2013. Envisioned as the ultimate comeback story, The Armstrong Lie instead presents a riveting, inside view of the unraveling of one of the most extraordinary legends in the history of sports.

'Ultimately, it's a cautionary tale," says the legendary producer and five-time Academy Award®-nominee, Frank Marshall (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button; Seabiscuit; The Sixth Sense; The Color Purple; Raiders of the Lost Ark), who had remained determined for years to make a film about Lance Armstrong.

'It was just such a good story. Who wouldn't want to believe in that story," says Alex Gibney of the Lance Armstrong legend and his new film. 'But it just didn't happen to be true."

Alex Gibney discusses his new film in detail, its circuitous route to the screen, and his relationship with Lance Armstrong in the following director's statement - prepared as he readied The Armstrong Lie for its international premier at the Venice Film Festival from his edit suite in New York.

Director's Statement: Alex Gibney

New York August 6th, 2013

A funny thing happened on the way to inspiration…

In 2008, I set out to make a film about a comeback. Lance Armstrong, a man who had cheated death, the 7-time-winner of the Tour de France and an inspirational figure who had raised over $300 million dollars to support those afflicted with cancer, had decided to return to cycling. Though he had been dogged by accusations of doping, he was going to return to the sport, at the ancient age of 38, to prove to everyone that he would race clean and still beat the field.

That sounded like a pretty good film to me.

Supported by the extraordinary producers Matt Tolmach and Frank Marshall, I would have unprecedented access to Lance (who, in classic Hollywood superstar fashion, would take a cut of the movie's 'back end" in exchange) as he set out to prove that he was still the best in the world.

My crew and I (including my longtime DP, Maryse Alberti) followed him all over the planet – Australia, California, Spain, New Mexico, Aspen, Austin, Italy – and then filmed the 2009 Tour de France with 10 cameras, on motos, in the team car, on the bikes of Lance Armstrong's teammates, and in super slo-mo with a Phantom. Not only did I have an extraordinary portrait of a sport but I also hung out with the legendary Lance, capturing candid moments and peppering him with questions in a series of formal interviews.

Even then, I wasn't naïve about the past. In 2009, I shot interviews with David Walsh (a self-styled Van Helsing to Armstrong's Dracula), ex-teammate Frankie Andreu, and whistleblowing cyclist Filippo Simeoni. Much to my surprise, the Lance Armstrong camp also gave me permission to speak to Michele Ferrari, the so-called 'Dr. Frankenstein" of Lance Armstrong's monstrous performances, a charming man who offered not only a specialised training program but an extraordinary knowledge of human physiology, racing strategy and an understanding of when to add the 'secret sauce."

That infuriated a number of Lance Armstrong's critics who refused to talk to me because they assumed that my access was a sign I was making a puff piece that was at odds with my reputation. After all, I had made a number of investigative films that tried to peel back the cover-up for abuses of power: 'Enron: the Smartest Guys in the Room," 'Taxi to the Dark Side," and 'Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God," among others. What was I thinking? Had I lost my grip?

Well, not entirely. But it was also true that I was tired of digging through the foul entrails of corruption. I was in the mood for a feel-good story. Even if Lance Armstrong had doped before – remember: 'no positive tests"! – if he could race clean at the age of 38 and beat the field, then that would be inspirational. During the 2009 Tour de France, I found myself on the legendary cycling peak, Mt. Ventoux, rooting for him. When he crossed the finish line with the lead riders and saved his spot on the podium, I knew I had a great ending for an upbeat film. After a year or so in the cutting room, I finished the film I set out to make. And then everything changed…

I discovered 'The Armstrong Lie."

In 2011, I watched Tyler Hamilton on '60 Minutes" reveal, in granular detail, how Lance had doped. Not long before that, another one of Lanc Armstrong's ex-teammates, Floyd Landis, had leaked more doping details and added, with grim emphasis, this line: 'Look, at some point, people have to tell their kids that Santa Claus isn't real." Certainly the US Department of Justice had no time for elves or flying reindeer. They initiated a criminal investigation, followed by a detailed inquiry conducted by Travis Tygart, the head of the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). That two-pronged approach – and the prospect of perjury prosecutions – punctured the wall of silence of 'omerta" so prevalent in the Peloton. Suddenly, many of Lance's former teammates came forward with extraordinary details of doping - transfusions on the team bus, motorcyclists carrying drugs, dumping needles, faking prescriptions - that could not be ignored.

This was not good news for the feel-good movie. On the other hand, it was more familiar territory for me. Over time, I dug back in to make a different kind of film. I spent more time talking to Betsy Andreu, Frankie's wife, who had always been a good source. I went back to others who were now willing to move beyond the familiar cover stories. I learned the granular detail of doping in the Peloton.

But to me, for this new film, doping was not the most important thing. After all, doping was an essential part of the culture of professional cycling. It was the lie that interested me. Lance Armstrong had doubled down on the lie. He hadn't just leaned on the test results; he had told everyone that they would have to be crazy to think that he, as a cancer survivor, would ever dope. In so doing, he made those who had defended him – including millions of cancer survivors around the world - accomplices to his deceit.

Then there was the abuse of power. The dirty secret of the Lance Armstrong story is that evidence of doping has been hiding in plain sight since 1999, the year of his first tour win. But Lance Armstrong was so powerful in his sport that he could protect and defend his lie with the arrogance and cruelty that he showed his cycling rivals on the road. This was becoming a film about winning-at all costs: the very thing I most admired about Lance on the bike – his will to win – was the very thing that enabled him, off the bike, to bully the weak to protect his reputation and growing fortune.

With this new movie in mind, I had to wonder what I was going to do with all the footage

from the feel-good movie. But Lance Armstrong himself offered me a solution when he told Oprah, in his prime-time confession, that his lie would never have been exposed had he not come back in 2009. Well, to me, that was like the first line in a good mystery story. Why had

he come back? I wondered what I had been witness to in 2009 and what did it mean now

that the truth about Lance was known? In making my new film, all roads seemed to lead back to re-examining the footage I had shot on Lance Armstrong's comeback year.

And what of my relationship with Lance Armstrong? After all, he had lied to me too. To my face, even. Well, in my career, that hadn't been the first time.

So I stayed in touch with Lance, off-and-on, throughout the investigations. Over time, even before Oprah, he came clean. He apologised for lying to me. And he pledged that he would sit before my cameras one more time. Perhaps that was his way of making things right or, just as likely, he still wanted to have some influence on his story. After all, he had proved himself to be one of the world's great storytellers, with a unique appreciation for the power of myth.

I was there in Austin, Texas, when Lance shot his interview with Oprah. I interviewed him briefly a few hours later and saw, for the first and only time, a slump in his shoulders that showed some kind of vulnerability. Then, a few months later, I interviewed him again. The subject of our talk, and my new movie, was not about the bike. It was about the lie. The Armstrong Lie.

Production

The origins of the documentary, The Armstrong Lie, stretch back for well over a decade. They begin with the legendary Hollywood producer, Frank Marshall.

One of the most respected filmmakers working in the industry today, Frank Marshall is best known as the five-time Oscar® winner behind such films as The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Seabiscuit, The Sixth Sense, The Color Purple and Raiders of the Lost Ark, and such recent hits as the Bourne film series. Perhaps less well known is Marshall's interest and involvement in the world of sports.

In addition to his work as a filmmaker, Frank Marshall (who ran cross-country and track as a student at UCLA and was a three-year varsity letterman in soccer) served for over a decade as a vice president and member of the United States Olympic Committee. He was awarded the Olympic Shield in 2005 and, in 2008, was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame for his service to the Olympic movement.

In the early 2000's Frank Marshall was approached by fellow US Olympic Committee member, Bill Stapleton – lawyer and agent to Lance Armstrong – with an eye towards making a feature film based on Armstrong's memoir, It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life. 'Back then I was kind of the go-to Hollywood guy if you had a story," says Frank Marshall. 'So they came to me and said, -What do you think we should do with this?' That's how it all started."

Frank Marshall brought the book to Matt Tolmach, who at that time was co-head of production at Columbia Pictures. He was also, as Frank Marshall knew, an avid cyclist.

'Frank Marshall and I knew each other and he knew that I was a serious cyclist myself, kind of a weekend warrior," says Tolmach, who was also well aware of Lance Armstrong's remarkable story.  'We were interested and we wanted to develop the movie," says Matt Tolmach, who soon found himself in a meeting with Lance Armstrong's rep, Bill Stapleton. 'I went to Frank Marshall's office in Santa Monica. I sat down, and there was Bill Stapleton who looks at me and says, -So I hear you're a cyclist… Pull up your pant leg.' Of course, I did. And like all dedicated roadies, my legs are shaved. He saw that, smiled, and said -Alright, let's talk.'

'We were interested and we wanted to develop the movie," says Matt Tolmach, who soon found himself in a meeting with Lance Armstrong's rep, Bill Stapleton. 'I went to Frank Marshall's office in Santa Monica. I sat down, and there was Bill Stapleton who looks at me and says, -So I hear you're a cyclist… Pull up your pant leg.' Of course, I did. And like all dedicated roadies, my legs are shaved. He saw that, smiled, and said -Alright, let's talk.'

Together, Frank Marshall and Matt Tolmach set about developing a feature film about Lance Armstrong with Matt Damon set for the leading role. Though 'one or two scripts," according to Frank Marshall, were developed, the idea of making an Lance Armstrong biopic was ultimately shelved. 'Movies about people who are still alive and in the news are complicated," explains Matt Tolmach. 'Because Lance Armstrong was such a household name it's hard to ask an audience to suspend what they know and what they see almost daily and accept someone else playing the part… Because he was still very much in the public eye, it seemed like an awkward proposition." Says Frank Marshall: 'We just never got to a place where we were ready to make the movie."

By August, 2008, however, the project would take a new tack. The 37-year-old Lance Armstrong, who at this point had been in retirement for three years, had decided to test his mettle that summer in Colorado in a race called The Leadville 100. After training and placing second (finishing just two minutes behind race winner, Dave Wiens), Lance Armstrong now contemplated the ultimate comeback. Having won the Tour de France a record seven times in a row (1999-2005), he would try to win it again in 2009.

It was at this time that Matt Tolmach realised that the movie he would make with Frank Marshall would be a nonfiction film – the real story of a Lance Armstrong comeback. 'It was a different story unfolding and it was a documentary," explains Matt Tolmach. 'Because it was a story that was happening in real life and real time, the best way to capture it was to go out and film it… I thought if we were to film a year in the life of this man, culminating in the Tour de France, that would be really interesting for people to see. What does that comeback look like? And what does it mean?"

Speaking with Lance Armstrong after the Leadville race, Frank Marshall and Matt Tolmach agreed it was the perfect time to make a documentary about the cyclist. 'Our one condition was that he let us follow him and cover the whole year," says Frank Marshall. 'He agreed to that. And that's how we got this unprecedented access to his life, his team and the Tour de France," says the producer of what would emerge as the film's remarkable inside view of Lance Armstrong's world (including such controversial figures as Italian physician and Armstrong cycling coach, Michele Ferrari).

Around the same time, Frank Marshall was involved with a passion project of his own, making a documentary for ESPN's 30 for 30 series (celebrating the US sports network's 30th anniversary with thirty sports docs). Frank Marshall's film, Right to Play, told the story of Norwegian speed-skater Johann Olav Koss's philanthropic works. Documentary filmmaker, Alex Gibney, meanwhile, was working on Catching Hell, the story of Chicago Cubs' baseball fans who had blamed their team's misfortunes on a fellow fan who'd interfered with a crucial play.

'We got to know each other on the 30 for 30 track for ESPN," says Frank Marshall of his relationship with Alex Gibney. 'If you look at Alex's Spitzer documentary (Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer) or indeed many of his films, he likes to examine why people tick. And so I thought, -Wouldn't it be interesting examine why this guy wants to make a comeback?' I knew we already had an exciting subject. And so Matt Tolmach and I talked about it. We decided to go with the best, and that's Alex Gibney."

'We were also in the Lance tent a little bit and we both knew enough to know that great documentaries need a more objective approach," says Tolmach. 'Alex was the master of great journalistic truth telling. And there was a lot about this guy [Armstrong], that was a mystery, but not the mystery that everybody is trying to unravel now. We just wanted to know what drove this guy. And we knew a great documentary would win or lose based on whether or not you could get inside the character."

For his part, director Alex Gibney knew little of Lance Armstrong or the world of competitive cycling. 'When I first met Lance Armstrong I told him, -I know you ride a bike and you're good at what you do, but beyond that I don't know much about your sport.' Alex Gibney did, however, know a thing or two about making documentaries - with an Oscar® nomination in 2006 for his film, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and an Oscar® win in 2008 for the hard-hitting, Taxi to the Dark Side.

'I had to learn in a hurry," says the director of his research. 'I started reading madly, watching cycling… I also bought a bike and started going out on the road just to get a sense of what it was like." So too, did Alex Gibney begin interviewing veteran journalists who had covered both the sport and Lance Armstrong. 'I got into some of the rumors, the accusations…. And also just what made the sport so interesting and how you get good at it."

Even then Alex Gibney was aware of the misgivings which had dogged both Lance Armstrong's career and the world of competitive cycling itself. 'I'd certainly heard about the allegations and discussed them with Matt Tolmach and Frank Marshall," says the director. 'The suspicions were always there, but again, you had to be careful because you could never really prove them."

Instead, Alex Gibney would focus on Lance Armstrong's comeback in the initial iteration of his film under the working title 'The Road Back." Joined by his production team, he began filming in late September 2008, following Armstrong through his intensive training and his attempt to win the Tour de France in July 2009 and again in July, 2010.

Together with his crew – including trusted cinematographer Maryse Alberti and soundman, David Hocs – Alex Gibney was given unprecedented access, filming Lance Armstrong in training rides in Austin, Texas, Sonoma, California and Aspen, Colorado; and then in competition in New Mexico, California, Australia, Italy and Spain in the build up to the 2009 Tour.

'We basically had a schedule where we covered his races and training, and then Alex Gibney would also interview him at home in Texas and cover his training regimen there," says Frank Marshall. 'We then went to the (2009) Tour and shot the entire three weeks of that race. We shot the next year at the Tour as well, when he continued to try and win again… That's where Lance Armstrong placed 23rd and kind of decided he was done."

Typically, Alex Gibney would run three to four cameras simultaneously. 'It was critical," says the director of his desire to make the racing footage as exciting as possible. 'You don't want it to seem like wallpaper."

Amongst Alex Gibney's innovations were the use of small digital cameras, early prototypes of the now ubiquitous GoPros – one positioned underneath an Lance Armstrong teammates' saddle pointing backwards, the other atop a set of handlebars pointing forward – to create a more immersive experience for the viewer. He also made use of state of the art Phantom digital cameras to film in super slow motion. 'It made you feel like you're in the sport," says Alex Gibney. 'And the sport is terribly exciting… I really wanted the cycling part to feel like an action movie. You want to feel that speed."

'In the end we were running ten cameras at the Tour," Alex Gibney continues. 'The way you do it in the Tour is you jump ahead to a point where you wait for the pack to come by and then you grab a few shots. Then you quickly jump back in the cars, get ahead of it again, station yourself, set up your cameras, and do it again. You want to be in the right place at the right time in addition to coordinating all your other cameras… This was a huge undertaking."

By late 2010 Alex Gibney, between his own and archival footage, had gathered over 200 hours of material – 'a Titanic amount of footage". Working with his initial editing team of Tim Squyres (Life of Pi; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and Lindy Jankura (Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson), he had all but completed the film in 2011– just as the legend surrounding Armstrong himself had begun to collapse.

'In point of fact we had virtually finished the film," says Alex Gibney. We had done everything. We had mixed it. We had color corrected the film. We had done everything but put on the final credits."

Though Lance Armstrong had dodged repeated doping allegations throughout his career, the credibility of his remarkable story came under more serious fire when in May 2010 former teammate, Floyd Landis, accused the legendary champion cyclist of using performance-enhancing drugs.

'From there, people began coming out of the woodwork," says Matt Tolmach of the events which would subsequently unfold, leading to a Federal investigation (where criminal charges were subsequently dropped) and a US Anti Doping Agency (USADA) investigation which would ultimately lead to Armstrong being stripped of his former titles and end his career.

'When Tyler Hamilton went on 60 Minutes, suddenly it was out in the open, says Alex Gibney of a damaging interview given by Lance Armstrong's former teammate to the popular US news program in May 2011. 'We knew the film as constructed would never fly."

'There were several options at that stage," says Frank Marshall. 'But it all depended on what would happen next... We were waiting to see what the final results would be of the investigations."

'The conversation we had at that point was that we owed it to the movie to hold on and turn it into something which really reflected what was going on, which is to say for the movie to ask the same questions that the public was asking," says Matt Tolmach. 'I don't want to call it a holding pattern because we were doing anything but holding. We were digging in and Alex Gibney was doing his investigative work. All of that culminated with the movie that is now The Armstrong Lie."

'I went back and started shooting interviews again in the fall of 2012," says Alex Gibney, who found that many of his subjects were now willing to talk more openly about the events which had transpired. 'We'd spent so much time on this story and had so much intimate access with Lance Armstrong that it seemed crazy not to finish it... Of course, the key would be to see whether or not Lance Armstrong himself would make himself available."

In November 2012, producers Frank Marshall and Matt Tolmach flew to Austin, Texas to meet with Lance Armstrong to discuss that very possibility. 'This was before Oprah," recalls Frank Marshall, citing Lance Armstrong's chilling confession which would take place in January 2013 on the popular US talk show. 'That's where he told us the whole story. And that's when Matt Tolmach and I sat down and called Alex Gibney and said, -Lance is willing to talk…' That's when we decided to go to Sony Classics and say, -We think we've got a movie now.'"

'I thought we might be the ones to do it first, but Oprah got there ahead of us," says Alex Gibney, who filmed Lance Armstrong on January 14, 2013 in Austen, Texas, just hours after his confession on Oprah. 'It's a rather unique interview," says Alex Gibney of their meeting, 'because you can sense a kind of wounded quality in Lance and a kind of vulnerability that I don't think would ever come again."

Alex Gibney continued to shoot while re-cutting material from his film's previous iteration, now working with editor Andy Grieve who had worked on his WikiLeaks documentary. For Alex Gibney and Andy Grieve, the biggest challenge now would be finding the film's structure. As Alex Gibney puts it: 'How were we going to integrate what we had shot before into a structure that was about Lance Armstrong doping?"

Alex Gibney continued to shoot while re-cutting material from his film's previous iteration, now working with editor Andy Grieve who had worked on his WikiLeaks documentary. For Alex Gibney and Andy Grieve, the biggest challenge now would be finding the film's structure. As Alex Gibney puts it: 'How were we going to integrate what we had shot before into a structure that was about Lance Armstrong doping?"

'In a way the Oprah interview gave us a clue," Alex Gibney continues. 'There was suddenly a mystery story at the heart of what we had filmed in 2009, which was why did he come back? And not only why did he come back, but what did we see in 2009 that would give us insight into that question and also the question of who Lance Armstrong was…

Suddenly we realised we had this special material that gave us a clue to Lance Armstrong and his character."

'The other challenge, of course, was that we were lied to," says Frank Marshall. 'And that was very difficult. I was a true believer, so it was a huge disappointment. It was a hard thing for us to go through." Having formed a friendship over 10 years with Lance Armstrong, Frank Marshall now describes their relationship as distant, but cordial. 'Lance Armstrong is an incredibly driven, amazing athlete with a lot of character flaws," says the producer. 'But he's a human being. I know his family. I know his kids... He's not a monster. But he is a flawed character." 'As people who started this journey making a heroic movie about Lance Armstrong, we've come a long way from there," agrees Matt Tolmach. 'It's a tough document in that way. But it's an honest document."

Perhaps most poignantly, Alex Gibney's film finds us all complicit to a degree in Lance Armstrong's outrageous deceit - a personal narrative which in hindsight seems so incredibly implausible, yet a story in which we all wanted to believe in.

'That was the beauty of his story," says Alex Gibney. 'That was the power of his story… It's the ultimate apotheosis. He's like the Phoenix rising from the ashes. He gets up out of his hospital bed and then decides to himself, -I'm going to win the Tour de France.' And low and behold, he does it – seven times… It was a very potent myth that Lance Armstrong inhabited. And a lot of people hung onto that myth, which we now know to have been a lie – that he didn't dope… Because it was the story that so many of us wanted to believe."

Timeline: Lance Armstrong

1971: September 18, born Lance Edward Gunderson in Plano, Texas.

1987: Becomes a professional triathlete at 16.

1993: Jul. 11, 1993: Wins first Tour de France Stage (stage 8) in his first Tour de France

1995: May 7 1995: Armstrong wins the Tour DuPont, the United States' most important race.

1996: Armstrong the year as the top-ranked cyclist in the world.

Summer '96: Competes at the Olympic Games in Atlanta, where he finishes 6th in the men's time trial and 12th in the men's road race.

Oct. 9 1996: Announces he has testicular cancer that has spread to his abdomen and lungs. His doctor puts the chances of recovery at 65 to 85 percent and describes the state of the cancer as "advanced."

Oct. 25 1996: undergoes brain surgery to remove two lesions at Indiana University Hospital in Indianapolis. He returns home after the chemotherapy.

1997:

Jan. 11 1997: Lance resumes training with the new Cofidis team in Wasquehal, France.

Oct. 1997: Founds the Lance Armstrong Foundation, later to be known as the Livestrong Foundation, to advocate for cancer research and support cancer survivors.

Oct. 15 1997: Joins US Postal Service Team

1998:

Jun 12, 1998: Wins the opening stage of the Tour of Luxembourg, his first win since he was treated for testicular cancer.

1999:

Jul. 25 1999: Wins 1st Tour de France title. Riding for the U.S. Postal Service team, Armstrong wins the race prologue along with the 8th, 9th and 19th stages. He becomes only the second American to win the Tour.

- During the 1999 TdF Lance tests positive for corticosteroids. Doping accusations are dropped after Armstrong produced a phony back dated prescription for a saddle sore cream that contained cortisone.

2000:

May 22, 2000: Publishes book It's Not About the Bike about his comeback from cancer.

Jul. 23, 2000: Armstrong wins his 2nd Tour de France title. – He's the second American to repeat as champion since Greg LeMond won the race in 1989 and 1990.

Nov. 8, 2000: USPS is investigated in a preliminary enquiry into doping, launched by the prosecuting office in Paris. The investigation was prompted by an anonymous note from France 3 TV journalists to prosecutor Jean-Pierre Dintilhac in Paris who claimed that plastic bags originating from US Postal team vehicles were transferred to a German car before being disposed of.

2001:

Jul 23, 2001: David Walsh takes Armstrong to task over USPS enquiry. Lance fields questions from Walsh about his relationship with Dr. Michele Ferrari at press conference.

Jul. 31, 2001: Armstrong wins 3rd Tour de France.

2002:

Jul. 28, 2002: Wins 4th Tour de France. Joins Jacques Anquetil, Bernard Hinault, Eddy Merckx and Miguel Indurain as the only riders to win four Tours.

Sep. 3 2002: After nearly 2 yrs, French authorities close USPS investigation due to lack of evidence.

- Lance donates $25,000 to the UCI

2003:

Jul. 27, 2003: Wins 5th Tour de France. (Only Miguel Indurain has 5 straight wins.)

Oct. 7 2003: Armstrong's book Every Second Counts is published.

2004:

May 24, 2004: Nike Creates Livestrong bracelet campaign

Jun. 15 2004: Armstrong is accused of taking performance-enhancing drugs in L.A. Confidentiel: Les secrets de Lance Armstrong written by David Walsh (The Sunday Times) and Pierre Ballester (former writer for l'Equipe). Emma O'Reilly (USPS team masseuse) revealed that she took clandestine trips to pick up and drop off what she concluded were doping products.

Jun. 22 2004: A French judge rejects the request by Lance Armstrong's lawyer to force the publisher of "L.A. Confidentiel" to include in each copy of the book a statement by Armstrong denouncing the book's accusation that he has engaged in doping during his career.

Jul. 2004: Armstrong 'attacks" Filippo Simeoni during TdF. (Simeoni told authorities that Michele Ferrari, also Armstrong's coach, helped him to dope. Armstrong called him a liar. Simeoni sued for defamation and lost).

Jul. 25, 2004: Wins 6th Tour de France, making him the winningest Tour rider ever.

Oct. 1, 2004: Lance's Dr. Ferrari is given a 12-month suspended jail sentence for malpractice by an Italian court based partially on testimony from racer Filippo Simeoni. Ferrari was involved with the US Postal Service Cycling Team until October 2004, helping Armstrong train during several of his seven consecutive Tour de France victories.

2005:

Mar. 31, 2005: Armstrong's former personal assistant Mike Anderson claims he found a box of androstenone while cleaning Armstrong's bathroom. Armstrong denied the claim and issued a countersuit. Armstrong and Anderson reached an out-of-court settlement.

Apr. 18 2005: Armstrong announces he is retiring from professional cycling.

Jul 24 2005: Wins his 7th and final Tour de France with Discovery Channel team.

Aug 23, 2005: French sports newspaper L'Equipe reports that Armstrong used EPO in 1999 to win his first of 7 consecutive Tours de France in their article 'Le Mensonge Armstrong" (The Armstrong Lie). Lance responds calling it a 'witch hunt".

Aug. 25 2005: "I have never doped, I can say it again, but I have said it for seven years " it doesn't help." "Armstrong on CNN's Larry King Live after media reports surfaced that urine samples taken from Armstrong in 1999 and then frozen tested positive for EPO.

By end of year, 55 million Livestrong wristbands are sold.

2006:

May 2006: Italian Court of Appeal in Bologna absolves Dr. Michele Ferrari of all charges.

May 31, 2006: Lance is cleared of doping allegations that stemmed from 1999 drug test. Report states re-testing fell far below scientific standards.

Jun. 23, 2006: French newspaper "Le Monde" reported it received a copy of Betsy Andreu's sworn statements before an arbitration panel in January claiming Armstrong told a doctor he had used the blood-boosting hormone EPO and other drugs. Betsy Andreu's testimony came in a legal dispute over whether Armstrong was owed a $5 million bonus for winning in 2004.

Jun. 26, 2006: Greg LeMond tells l'Equipe newspaper that Armstrong threatened him for criticizing his relationship with Dr. Ferrari. "Lance threatened me," he said. "He threatened my wife, my business, my life. His biggest threat consisted of saying that he (Armstrong) would find ten people to testify that I took EPO."

Sep. 12, 2006: Frankie Andreu and anonymous former teammate admit EPO use to NYT. Andreu said that he took EPO for only a few races. Both of Armstrong's former teammates also said they never saw Armstrong take any banned substances.

Sep. 13 2006: In a statement, Armstrong lashes out against NYT article detailing Andreu's confession calling it a 'blatant attempt to associate me and implicate me with a former teammate's admission that he took banned substances during his career"

2007:

July 3, 2007: Lance vehemently denies doping in interview with CBS News journalist and cancer survivor Bob Schieffer at the Aspen Ideas Festival. "I was on my death bed. You think I'm going to come back into a sport and say, 'OK, OK doctor give me everything you got, I just want to go fast?' No way. I would never do that."

2008:

Sept. 9 2008: Announces his intention to return to professional cycling.

Dec. 1 2008: Armstrong announces on his website that he will participate in the 2009 Tour de France.

2009:

Jan. 18, 2009: Armstrong finishes 64th out of 133 starters in the 30-lap, 51-kilometer criterium in Adelaide, Australia, his first race since winning his seventh Tour de France in 2005.

Feb 13, 2009: Armstrong and Irish journalist Paul Kimmage face off at Tour of California press conference over 'cancer" comments in which Kimmage refers to Lance as a cancer in the sport.

Mar. 23, 2009: Involved in a crash in the first stage of the Vuelta a Castilla y León in Baltanás, Spain and breaks his collarbone. He's back training four days after surgery.

April 2009: the AFLD, France's anti-doping agency, accuses Armstrong of not fully cooperating with a drug tester. He denies the accusation. The case known as 'shower-gate" is closed later that month.

Jul. 27, 2009: Armstrong finishes 3rd in the 2009 Tour de France with team Astana; his teammate Alberto Contador wins.

2010:

May 20, 2010: Floyd Landis admits he was using performance-enhancing drugs when he rode on the U.S. Postal Service team and accused team members, including Armstrong, of using performance-enhancing drugs. Armstrong denies the allegations.

"It's our word against his word. I like our word. We like our credibility. Floyd lost his credibility a long time ago." " Armstrong's response to cyclist Floyd Landis' accusations of systemic doping in the U.S. Postal cycling team.

May 25, 2010 Federal authorities investigating accusations that Armstrong and other top cyclists engaged in doping consider whether they can expand the inquiry beyond traditional drug distribution charges to include ones involving fraud and conspiracy.

Jul. 25, 2010: Armstrong finishes 23rd in the Tour de France on team RadioShack .

September 2010: Betsy Andreu says she spoke to a federal agent investigating Armstrong and other cyclists. Betsy claimed Armstrong admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs in a hospital room in 1996 while battling cancer. Armstrong denies the allegation.

2011:

January 2011: Sports Illustrated published its investigation into Lance Armstrong on its website under the title of the -The Case against Lance Armstrong'. The article quotes Armstrong's 1995 teammate Stephen Swart as saying Armstrong was "the instigator" for some team members to use EPO.

Feb. 16, 2011: Armstrong announces 2nd retirement: says he is retiring, again, to spend more time with his family and to focus his efforts on his campaign against cancer.

May 20, 2011: Former teammate Tyler Hamilton tells CBS News that he and Armstrong had taken EPO together during the 1999, 2000 and 2001 Tours de France. A 60 Minutes investigation that aired May 22nd says that two other teammates told investigators that they had witnessed Armstrong taking banned substances or supplied him with such.

- Armstrong's rep, former Bill Clinton strategist Mark Fabiani, writes, 'Tyler Hamilton is a confessed liar in search of a book deal – and he managed to dupe 60 Minutes, the CBS

Evening News, and news anchor Scott Pelley. Most people, though, will see this for exactly what it is: More washed-up cyclists talking trash for cash." Tyler Hamilton has turned in his cycling gold medal to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency."

May 21 2011: George Hincapie tells FDA Armstrong took PEDs. CBS News reported that, "Hincapie testified that he and Armstrong supplied each other with the endurance-boosting substance EPO and discussed having used another banned substance, testosterone, to prepare for races."

2012:  Feb. 3, 2012: U.S. federal prosecutors officially drop the criminal investigation (sparked by Landis' confession) of Armstrong with no charges nearly 2 yrs after they began looking into allegations that he and teammates committed a variety of possible crimes by doping including defrauding of the government, drug trafficking, money laundering and conspiracy. Tygart of USADA vows to continue to investigate Armstrong.

Feb. 3, 2012: U.S. federal prosecutors officially drop the criminal investigation (sparked by Landis' confession) of Armstrong with no charges nearly 2 yrs after they began looking into allegations that he and teammates committed a variety of possible crimes by doping including defrauding of the government, drug trafficking, money laundering and conspiracy. Tygart of USADA vows to continue to investigate Armstrong.

-'I am gratified to learn that the U.S. Attorney's Office is closing its investigation," Armstrong said in a statement. 'It is the right decision and I commend them for reaching it. I look forward to continuing my life as a father, a competitor, and an advocate in the fight against cancer without this distraction."

Jun. 12 2012: USADA notifies Armstrong, Johan Bruyneel (team manager), Dr. Pedro Celaya (team doctor), Dr. Luis Garcia del Moral, Dr. Michele Ferrari, and Pepe Marti of alleged anti-doping rules violations under UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) and state that they are opening a formal action against each respondent. Armstrong is immediately banned from triathlons as a result. USADA is empowered to bring charges that could lead to suspension from competition and the rescinding of awards but does have not authority to bring criminal charges.

Jun. 13. 2012: Lance responds to USADA's charges: "I have never doped, and, unlike many of my accusers, I have competed as an endurance athlete for 25 years with no spike in performance, passed more than 500 drug tests and never failed one."

- Dr. Ferrari was officially charged by USADA with administration and trafficking of prohibited substances. As Ferrari did not formally contest this indictment, he was issued a lifetime ban from professional sport in July 2012.

Jun. 29, 2012: USADA officially charges Armstrong with a violation, accusing him of doping during most of his cycling career and participating in a doping conspiracy.

Jul. 9 2012: Armstrong files a lawsuit in federal court in Austin, TX against the USADA, but a judge throws it out the same day. The next day, Armstrong refilled the suit, while three former U.S. Postal Service cycling team associates received lifetime bans.

Aug. 20 2012: A federal judge throws out Armstrong's revised lawsuit, leaving him three days to decide if he will head to arbitration to fight charges.

Aug. 23 2012: Armstrong drops fight against doping charges. "The toll this has taken on my family, and my work for our foundation and on me leads me to where I am today – finished with this nonsense," he said in a release.

Aug. 24, 2012: USADA strips Armstrong's seven Tour de France titles that he won from 1999-2005, saying that he used PEDs. USADA has handed down a lifetime ban to retired Lance Armstrong relating to doping practices from his time on the US Postal Service team. Armstrong had declined to contest USADA's charges, giving up his right to appear before an independent arbitration panel.

Oct. 10 2012: USADA releases its 'reasoned decision" document detailing the evidence it has amassed against Lance Armstrong. Frankie Andreu, Michael Barry, Tom Danielson, Tyler Hamilton, George Hincapie, Floyd Landis, Levi Leipheimer, Stephen Swart, Christian Vande Velde, Jonathan Vaughters and David Zabriskie were part of a 26-strong group that gave written testimonies.

Oct. 17, 2012: Armstrong steps down as chairman of his Livestrong Cancer Foundation. Nike terminates its contract with Armstrong. Anheuser-Busch, RadioShack, and Trek Bicycle and Giro sever ties with him as well.

Oct. 22, 2012: The International Cycling Union announces that it will not appeal the United States Anti-Doping Agency's ruling to bar Lance Armstrong for life from Olympic sports for doping and for playing an instrumental role in the team-organized doping on his Tour de France-winning cycling squads. That decision formally strips Armstrong of the seven Tour titles he won from 1999 to 2005.

Nov 4, 2012: Lance Armstrong resigns from Livestrong's board of directors, cutting all official ties with the charity he founded 15 years ago while he was treated for testicular cancer.

Nov 30, 2012: Sports Illustrated dubs Armstrong 'Anti-Sportsman of the Year'.

Dec 4 2012: The Sunday Times announces it's suing Lance for up to 1.2 million euros having made a libel payment in 2006.

Dec 6 2012: UCI officially nullifies Armstrong's Tour de France titles and results since August 1998. Lance Armstrong has officially lost his seven Tour de France titles and all of his other results after July 1998.

2013:

Jan 14, 2013: Armstrong apologises to his Livestrong staff and confesses to doping in an interview with Oprah Winfrey.

Feb 6. 2013: USADA's initial deadline for Armstrong to answer questions about doping under oath. Deadline is extended.

Feb 22, 2013: DOJ Joins Lawsuit Alleging Lance Armstrong and Others Caused the Submission of False Claims to the U.S. Postal Service

The Armstrong Lie

Release Date: March 13th, 2014

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview